The Centennial of the Russian Revolution

November 7, 2017 marks the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution and the establishment of the world’s first socialist state. To commemorate the occasion, People’s World is presenting a series of articles that present wide-angled assessments of the revolution’s legacy, the Soviet Union and world communist movement which were born out of it, and the revolution’s relevance to radical politics today. Proposals for contributions are welcome and should be emailed to cjatkins@peoplesworld.org. Other articles in the series can be read here.

From the early days of the Russian Revolution all the way up to recent generations, the socialist bloc was a particular inspiration not only for celebrated revolutionaries like Fidel Castro but also for the global South in general and its diaspora (e.g., Blacks, Asians, Pacific Islanders, Arabs in the colonizing countries).

In the Second Declaration of Havana, of 1962, Fidel declared optimistically that “the duty of every revolutionary is to make the revolution. It is known that the revolution will triumph in America and throughout the world, but it is not for revolutionaries to sit in the doorways of their houses waiting for the corpse of imperialism to pass by.

“The role of Job doesn’t suit a revolutionary,” he said. “Each year that the liberation of America is speeded up will mean the lives of millions of children saved, millions of intelligences saved for culture, and an infinite quantity of pain spared the people.”

Fidel was speaking from Cuba’s capital, but he was aware of the battle the Vietnamese resistance was fighting, the anti-imperialist and anti-colonial battles growing all over the African continent, and nascent movements in Latin America in countries like Colombia—and he knew the source of inspiration for all of these movements.

The problems our people endure while facing the barbaric system of capitalism have been a concern for many of our revolutionaries, in the global South and North, and their concerns found a firm ally in the new, post-Czarist, anti-capitalist Soviet government born out of the Bolshevik Revolution whose centenary we celebrate.

Lenin as catalyst

From a group of Black veterans and Black Caribbean intellectuals to a short-lived People’s Republic on the African continent, and so much in between, the peoples of the global South have been part and parcel of struggles against fascism, exploitation, and capitalism.

On the death of one of the Russian Revolution’s chief architects, Black nationalist Marcus Garvey offered this eulogy at a public gathering in New York City:

“One of Russia’s greatest men, one of the world’s greatest characters, and probably the greatest man in the world between 1917 and 1924, when he breathed his last and took his flight from this world… We as Negroes mourn for Lenin because Russia promised great hope not only for Negroes but to the weaker people of the world.”

Garvey was able to honor Lenin even though ideologically the two men had differences. Garvey’s undiluted admiration did not commit him to communism, but it did affect at least one of Garvey’s admirers.

A young French colonial from Southeast Asia, Nguyễn Sinh Cung, was laboring in New York and attending Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association. The young man, who would become known to history as Ho Chi Minh, was transformed from being a Vietnamese nationalist to a communist after reading Lenin’s works in the early 1920s. He went on the lead a successful liberation struggle against both French and U.S. imperialism.

Closer to home and far from French-occupied Indochina, some Black World War I veterans formed the African Blood Brotherhood (ABB) in 1919. This small cadre of mostly Black men and women were mostly Marxists. Emboldened while at the front and away from the racial paranoia and Jim Crow of the United States, these veterans, led by a British colonial from Nevis and St. Kitts, Cyril Briggs, were few in number, but their rhetorical impact in Black discourse spread the breadth of the country via Black newspaper syndication and their own magazine, The Crusader.

Harry Haywood followed his brother, Otto Hall, into the ABB. Harry Haywood—lifetime pseudonym of Haywood Hall—defined the focus of the group in his memoir, Black Bolshevik:

“The Brotherhood rejected Garvey’s racial separatism. They knew that Blacks needed allies and tied the struggle for equal rights to that of the progressive section of white labor. In the 1918-19 elections, the Brotherhood supported the Socialist Party candidates. The Crusader and the ABB were ardent supporters of the Russian Revolution; they saw it as an opportunity for Blacks to identify with a powerful international revolutionary movement. It enabled them to overcome the isolation inherent in their position as a minority people in the midst of a powerful and hostile white oppressor nation. Thus, The Crusader called for an alliance with the Bolsheviks against race prejudice. In 1921, the magazine made its clearest formulation, linking the struggles of Blacks and other oppressed nations with socialism… ”

Like other radicals, these Black militants would not find allies in the two capitalist parties. The Democrats had been pro-slavery, and their party then saturated the Deep South. They could be no friend to what was at the time called the Negro Question.

The Republicans, the party of Lincoln and radical abolitionists, had already taken their Black membership for granted. It had been a staunchly anti-slavery party but reneged on the promised 40 acres and a mule in favor of more land grabbing and railroad expansion for Northern industrialists.

Briggs recognized immediately the importance of Lenin’s discourse of self-determination and the emerging Soviet Union’s commitment to minority rights.

With the formation of the Communist Party of America (later renamed CPUSA) in 1919, Briggs, who like Ho Chi Minh, was drawn to Lenin’s and the Soviet position on national minorities, saw the young CP as the Blood Brotherhood’s natural ally.

Briggs, Harry Haywood, and his brother Otto soon joined the party. By 1925, the Brotherhood was dissolved.

Communist Parties

Communist Parties would in time spring up all over both the developed and colonial worlds, inspiring First World workers and intellectuals to better arrange their societies and Third World insurgents to see the logical horizon of their liberation aspirations.

In the U.S., such luminaries as Paul Robeson, Ossie Davis, and Ruby Dee, did not join the Communist Party, but they were its allies, public defenders, and engaged side by side in many of the CPUSA’s campaigns and in defending the Soviet Union in particular.

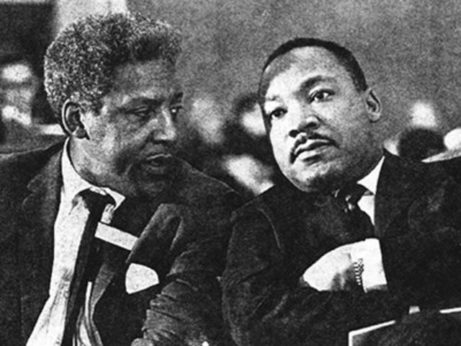

Others did take the step of signing a party card. One such person, inspired by the Russian Revolution, was a young gay Black man named Bayard Rustin, later known as one of the key advisers to Dr. Martin Luther King and an organizer of the March on Washington. Rustin was, in the 1930s, a member of first the Young Communist League and then the CPUSA.

Many in the Caribbean region, mostly comprising French and British colonies at the time of the Bolshevik Revolution, also gained inspiration from 1917.

The Trinidad-born Black communist, Claudia Jones—pseudonym for Claudia von Cumberbatch—came to the United States, joined the CPUSA in the mid-1930s, and rose in its ranks as she castigated the feeble lip-service of liberal capitalism towards the plight of Blacks. She was equally an advocate of women’s rights, workers’ rights, and communism:

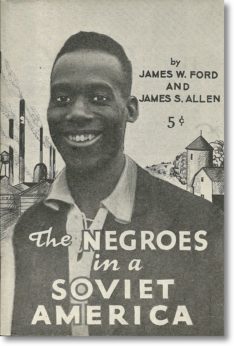

“To the extent, further, that the cause of the Black woman worker is promoted, she will be enabled to take her rightful place in the Black-proletarian leadership of the national liberation movement and, by her active participation, contribute to the entire American working class, whose historic mission is the achievement of a Socialist America—the final and full guarantee of woman’s emancipation.”

The French colonial, Martinique-born Aime Cesaire’s Discourse on Colonialism is a brief but angry indictment of capitalism. A member of the Communist Party of France, he was a poet, politician, and public defender of the Soviet Union.

In British Guyana, a young Walter Rodney was inspired by the Bolsheviks in general, Lenin in particular. Like Garvey before him, in Rodney’s eyes Lenin’s writings and deeds branded the Russian a “revolutionary intellectual,” an assertion that Rodney says put him at odds with his anti-communist bourgeois university professors. Rodney, this son of Guyana, would, like Ho Chi Minh, embrace Marxism and become a revolutionary intellectual of his own merit, penning the seminal, decidedly Marxist study, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, among other working-class research, before returning to his native land after working in Tanzania to organize radical change. He was assassinated in 1980.

There were some twists. Elsewhere in the Caribbean, the first Communist Party of Cuba (CPC) was founded in 1925 in Havana by Blas Roca and others. Cuba’s most world-renowned communist, Fidel Castro, did not join the CPC, though. His younger brother, Raul, is rumored to have become a communist first and did, in fact, introduce fellow-traveler Ché Guevara to the leader of the Cuban Revolution in Mexico.

The CPC did not support the armed rebellion until the eleventh hour, when they sent an emissary to the mountain hideout. So one might say the CPC joined Fidel, not the reverse.

That early CPC attracted some surprising members. Shortly after her death, the Miami Herald ran a report on newly released U.S. State Department documents concerning Cuban singer Celia Cruz. Better known in her later life as an anti-communist, the newspaper’s report revealed she had been barred by the State Department from entering the U.S. to perform with her band, La Sonora Matancera, due to her membership in the CPC and was only removed from the government’s watch list in 1965.

Some have speculated Cruz’s party membership was a passive act, but this doesn’t seem reasonable given the importation of Jim Crow laws by the U.S. during its occupation of the island. Cruz, like many Black Cubans, would have been keenly aware of these laws, the impoverishment of Black Cubans, and the indifference of bourgeois society to their needs.

Escaping capitalism’s circles of Hell

At a time when everyone was chasing Europe, and many went further to the logical, least civilized extension of European civilization—Nazism—the Bolsheviks offered an alternative option to what we now crudely term “the 99 percent.”

To underline the logic that links the ascent of Europe with Nazism, another colonial academic framed it well. The Cuban Revolution’s key philosopher and head of Casa de Las Américas, Roberto Retamar Fernández, observed in his 1971 essay, Caliban: Notes Toward a Discussion of Our Culture in Our America: “The manner in which a bourgeoisie develops at the expense of the popular classes’ brutalization is memorably demonstrated, taking England as an example, in some of the most impressive pages of Das Kapital. ‘European America,’ whose capitalism succeeded in expanding fabulously—unhampered as it was by the feudalistic order—added new circles of Hell to England’s achievements: the enslavement of the Negro and the extermination of the indomitable Indian.”

For the rebellious colonial subjects, the Russian Revolution, the Communist International, and the growth of the communist parties it chartered must have made the likelihood of an anti-racist, anti-fascist, communist future more a reality and a potent antidote to “new circles of Hell” of continued European domination.

Short-lived but notable, post-colonial Africa saw several socialist revolts—Burkina Faso, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Angola, and Mozambique to name a few.

The continent got one “People’s Republic,” an avowedly revolutionary Marxist-Leninist state. The People’s Republic of the Congo, with its capital, Brazzaville, had been a French colony. Between 1970 and 1991, it had joined the pantheon of nations striving to model its development in ways counter to what Europe had offered the world. It began with its leader, Alphonse Massamba-Débat, who in 1963 declared himself a Marxist-Leninist—the first African leader to do so—and initiated a program of “scientific socialism.” The country’s main ally and partners during its two decades of existence were the Soviet Union and Eastern bloc countries.

A new Bolshevik Thesis

Despite the early works of African Blood Brotherhood and Communist Party USA members in particular, and those insurgent communist parties and communist-inspired liberation movements around the world in general, the official history still steers our attention for radical examples elsewhere.

The Civil Rights Era of the 1950s-60s remains our focal point for the quintessential period of radical change in the US. This era, more or less, begins when a “seamstress” refused to give up her seat on a bus because, we are told so many times, she was tired. The era ends more or less when Dr. King is assassinated by a lone gunman. Then, Nina Simone lamented sourly, we got disco.

Like trickle-down capitalism, these histories are bold lies, beginning with Rosa Parks, who was a trained organizer and high-ranking official with the NAACP. Given the Jim Crow restrictions on Blacks going into white stores, what Black woman of Parks’ era was not a “seamstress”?

But if leaders of this movement like Parks, and the aforementioned Rustin, were trained, someone had to train them, and people had to, in turn, train those trainers. Parks did not get her start as a political activist on a Montgomery bus in 1955. Along with her husband, she was already active in the early 1930s around the case of the Scottsboro Boys—nine young Black men falsely accused of rape—whose defense campaign was largely spearheaded by the Communist Party. And of course, as mentioned, Rustin was for several years in the CP, a fact which, along with his sexuality, was used by the establishment to undermine King’s work. Official history seems disinterested in opening the files and illuminating the revolutionary lineage of these Civil Rights heroes.

While our gaze is fixed on the 1960s as the time of radical resistance, the body of global activism must redirect our attention to the initial decades after 1917 as the more radical epoch, that heavy stone of the Bolshevik Revolution was dropped into the stagnant pond of reactionaries, and the ripples produced a new chapter in the history of women’s liberation; militant labor strikes; anti-racist, anti-colonial, and anti-fascist insurgencies, Mexico City 1968, and yes, ultimately, the U.S. Civil Rights movement.

These people were fighting to stop the past from becoming the present and lingering like a plague into the future.

And, if this thesis is true, it forces us to revise these histories since not only were many of the key players in later movements inspired by people like Marx, Lenin, and Stalin, many of them were politically awakened by the efforts of these men. But this is not just an academic exercise. Since the collapse of the Soviet bloc, the fascists have been very busy to bring the past back upon us, and we must be encouraged that what was done before can be done again.

The ultimate lesson to be drawn from the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, and the revolutions it has inspired over the last 100 years, is that collective and determined militant action against reactionary regimes can succeed.