Following the U.S. Supreme Court’s historic 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision that declared all laws establishing segregated schools to be unconstitutional, the Little Rock Nine, a group of nine African-American students, enrolled in Little Rock Central High School in 1957. Their enrollment was initially prevented by Arkansas Gov. Orval Faubus.

Pres. Dwight D. Eisenhower intervened with federal troops to accompany the teenagers’ admission. He also federalized the entire 10,000-member Arkansas National Guard, removing it from the governor’s hands.

Delivering a television speech from the Oval Office, Eisenhower explained his actions to the country: “Speaking from the house of Lincoln, of Jackson, and of Wilson,” he said, “my words would better convey both the sadness I feel in the action I was compelled today to take, and the firmness with which I intend to pursue this course until the orders of the federal court in Little Rock can be executed without unlawful interference.” He deplored “mob rule” in Little Rock and “the call of extremists to violence.”

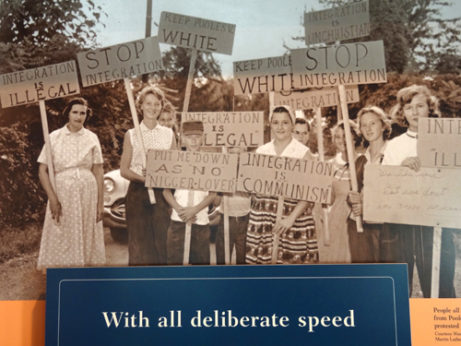

The nine students began attending classes at the previously all-white high school 60 years ago, on Sept. 25, 1957, entering the building through angry, hateful crowds.

The Little Rock School Board agreed to comply with the high court’s ruling, and planned a gradual integration beginning in September 1957. Nine black students registered. With the guidance of the NAACP, they had been selected on the criteria of excellent grades and attendance. The “Little Rock Nine” included Ernest Green, Elizabeth Eckford, Jefferson Thomas, Terrence Roberts, Carlotta Walls LaNier, Minnijean Brown, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Thelma Mothershed, and Melba Pattillo Beals. Ernest Green was the first African American to graduate from Central High School.

All did not go smoothly. They students were subjected to a year of physical and verbal abuse, including an acid attack and an attempted immolation. They had been warned they would have to tolerate a lot of ill will, and were warned not to fight back if anything happened.

As the school year ended, Faubus tried a new tack to postpone desegregation of public high schools. In September 1958, Faubus signed acts that enabled him and the Little Rock School District to close all public high schools, thus preventing both black and white students from attending. A referendum to either condone or condemn Faubus’ law took place on September 27. Faubus promised to continue segregation by leasing the public school buildings to private schools, which would educate white and black students separately. Faubus won the referendum, but his plan to open private schools failed. Some citizens of Little Rock blamed the black community, which became a target for hate crimes. That year came to be known as the “Lost Year.”

The town’s teachers were forced to swear loyalty to Faubus and attend school every day to prepare for the possibility of their students’ return. The many months that the schools stayed empty only served as a cause for uncertainty in their professional futures.

In May 1959, after the firing of 44 teachers and administrative staff from the city’s high schools, three segregationist board members were replaced with three moderate ones. The new board reinstated the staff members to their positions and then proceeded to reopen the schools. The black students who returned to the high schools were still forced to walk through mobs to enter the school and were subjected to continued physical and emotional abuse.

Little Rock Central High School still functions as part of the Little Rock School District, and is now a National Historic Site that houses a Civil Rights Museum, administered in partnership with the National Park Service, to commemorate the events of 1957.

Pres. Bill Clinton, a former governor of Arkansas, honored the Little Rock Nine in November 1999 when he presented them each with a Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian award bestowed by Congress. It is given to those who have provided outstanding service to the country. Recipients must be co-sponsored by two-thirds of both the House and Senate.

In 2007, the United States Mint made available a commemorative silver dollar to “recognize and pay tribute to the strength, the determination and the courage displayed by African-American high school students in the fall of 1957.” The obverse depicts students accompanied by a soldier, with nine stars symbolizing the Little Rock Nine. The reverse depicts an image of Little Rock Central High School, ca. 1957. Proceeds from the coin sales are to be used to improve the National Historic Site.

The Little Rock Nine were invited to attend the inauguration of Pres. Barack Obama. At this writing eight of the nine are still living.

From Wikipedia and other sources.