Frank H. Little was an American labor leader who was lynched in Butte, Mont., for his union and anti-war activities. He joined the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in 1906, organizing miners, lumberjacks, and oil field workers. He was a member of the union’s executive board when he was murdered 100 years ago, on August 1, 1917.

Little was born in 1879, the son of a Cherokee mother and a Quaker father. In Fresno, Calif., he worked as a union organizer with the Western Federation of Miners before becoming active with the IWW.

He took part in the free speech campaigns among workers in Fresno in 1910. Little and several hundred workers were arrested for violating a city ordinance; he was reported to have refused to work on the city rock pile. Many more IWW workers came to the city and struck in support. He also led free speech efforts in Spokane, Wash., and Missoula, Mont. As a “footloose” organizer, Little was involved in organizing lumberjacks, harvesters, metal miners and oil field workers into the One Big Union, the IWW.

On one occasion in Spokane, he was sentenced to 30 days in prison for reading the Declaration of Independence. He also successfully organized Mexican and Japanese fruit and construction workers in the San Joaquin Valley of California into IWW Local 66. He played a role in the formation of the Agricultural Workers Organization.

In August 1913, Little and fellow IWW organizer James P. Cannon arrived in Duluth, Minn., to support the strike of ore-dock workers against the Great Northern Railway over dangerous working conditions. In the course of the strike he was kidnapped, held at gunpoint outside of the city, and dramatically rescued by IWW supporters. By 1916, Little was helping mine workers on strike at the Mesabi Range in Minn.

As a Wobbly anarcho-syndicalist, Little was a strong opponent of capitalism and World War I, along with a faction of the Socialists. While General Secretary-Treasurer William Haywood and members of the General Executive Board shared Little’s opinions about the war, they disagreed about whether to create anti-war agitation. When the U.S. joined the war in April 1917, Ralph Chaplin, editor of the IWW’s newspaper Solidarity, claimed that opposing the draft would destroy the IWW by visiting unprecedented government repression upon the union. Other board members argued that organized labor would not have the power to stop the war until more workers were organized, and the union should continue to focus on organizing workers at the point of production; their actions might incidentally impede the war effort.

Little refused to back down on this issue and argued that: “…the IWW is opposed to all wars, and we must use all our power to prevent the workers from joining the army.” In the summer of 1917 in Butte, Mont., he said that soldiers serving in Europe were “Uncle Sam’s scabs in uniform.” With a recently broken leg, he had gone there to support union organizing after 168 men died in early June 1917 in a fire at the Granite Mountain & Speculator Mines owned by Anaconda Copper. The mine workers formed a new union, Metal Mine Workers’ Union (MMWU), and were joined in a strike by other trades. A federal mediator persuaded the other workers to return to work for the war effort.

The striking Anaconda Copper workers had been subject to attack by a “home guard” organized by the company, and newspapers worked to undermine public support for the workers. Little created a picket line at the mines, persuaded women to join the lines, and ultimately encouraged the other trades to join the strike. During this period, he also spoke out against U.S. involvement in the war.

In the early hours of August 1, 1917, after a speech that the press labeled a “treasonable tirade,” six masked men broke into the boardinghouse where Little was staying. The men initially kicked in the wrong door in the boardinghouse, claiming to be law officers. Little was beaten in his room and abducted while still in his underwear. He was bundled into a car which sped away. Little was later tied to the car’s rear bumper and dragged over the granite blocks of the street. Photographs of his body clearly show that his knee-caps had been scraped off. Little was taken to Milwaukee Bridge at the edge of town where he was hanged from the railroad trestle, dying of asphyxiation. It was also found that his skull had been fractured by a blow to the back of the head caused by a rifle butt.

A note with the words “First and last warning” was pinned to his thigh, referring to earlier vigilantes giving people three warnings to stop objectionable actions. The note also included the initials of other union leaders, suggesting they were next to be killed.

Paradoxically, his murder fueled passage of state anti-sedition laws that were later used to persecute and imprison Wobblies.

Although no one was apprehended or prosecuted for Little’s murder, there have been a number of speculations. The author Dashiell Hammett was working as a strike-breaker in Butte for Pinkerton’s, and allegedly turned down an offer of $5,000 to assassinate Little. Hammett later made use of his experiences in Butte to write Red Harvest. In her memoirs the playwright Lillian Hellman, Hammett’s companion, said he told her he was offered to murder Little: “Through the years he was to repeat that bribe offer so many times that I came to believe…that it was a kind of key to his life. He had given a man the right to think he would commit murder.”

Union leaders who had seen Little’s body at the time insisted that one of the murderers was Billy Oates, a notorious hired thug employed by Anaconda. The rationale for Oates’ involvement was a small hole at the back of Little’s head that had been “inflicted by the steel hook used by Oates on the stub of his amputated right arm.” Over the next nine years two further men were named as possibly being involved in the lynching.

At the time of the 1918 IWW conspiracy trial in Chicago, IWW lawyers questioned why Ed Morrissey, who had been Butte’s chief of detectives at the time of the murder, had taken a twenty-day leave of absence on the day following the killing. It was alleged at the trial that Morrissey had scratches on his face. The autopsy of Little’s body found that he had tried to fight off his assailants and that he had someone’s skin under his fingernails. In 1926, William Francis Dunne identified Peter Prlja as one of the death squad. Prlja was at the time a motorcycle officer in the Butte police department and like Oates had worked as a security guard for Anaconda.

An estimated 10,000 workers lined the route of his funeral procession, which was followed by 3,500 more. He was buried in Butte’s Mountain View Cemetery. His grave marker reads, “Slain by capitalist interests for organizing and inspiring his fellow men.”

An estimated 10,000 workers lined the route of his funeral procession, which was followed by 3,500 more. He was buried in Butte’s Mountain View Cemetery. His grave marker reads, “Slain by capitalist interests for organizing and inspiring his fellow men.”

The road to labor rights has been bloody indeed.

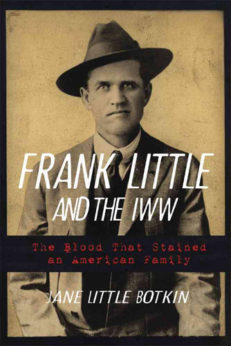

A giant hole in American labor history has been filled by Jane Little Botkin in her new title, Frank Little and the IWW: The Blood That Stained an American Family.

Travis Wilkerson’s 2002 film An Injury to One tells the story of Frank Little and his lynching.

Sources: Wikipedia and Sal Salerno in the Encyclopedia of the American Left.

Comments