The recent debate over the Green New Deal got me thinking about a lecture I gave in 2018 at the Columbia University Seminar on Energy Ethics. The faculty who attended were mostly environmental lawyers and scientists. I am neither. But they asked me to discuss “The Fragility of the Blue-Green Alliance”—not so much the formal partnerships between union and environmental groups but rather the complex challenges of bridging differences between workers and environmentalists.

Our views on climate change reflect our social and economic positions, which in turn reflect multiple factors—class, race, ethnicity, gender, place, and religious and ethical frameworks. Any discussion of climate change or environmental policies must acknowledge not only that individuals have different stakes in the environment and the economy but that sometimes, those stakes are themselves contradictory.

Working-class people and their communities are harmed by both environmental and economic injustices, and they have few economic choices. Solutions that might seem obvious, like ending the use of coal, can come with real costs to workers and their communities, even as they address environmental injustices and climate change.

In talking with colleagues at Columbia, I drew on a local example, from an article in the New York Times, “How Skipping Hotel Housekeeping Could Help the Environment and Your Wallet.” The article described how hotels were promoting opting out of daily room cleaning as a sustainability program because it reduced the hotels’ use of electricity, water, and chemicals. Customers could earn food and beverage credit by skipping housekeeping. But, I asked, sustainability for whom? As the Chicago Tribune reported in 2014, “green programs” like this were killing jobs and cutting wages as housekeepers lost tips and had to work harder, since fewer workers now had to clean rooms after guests left, but with the same hours as before.

Sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild offers another example in her book, Strangers in Their Own Land. Hochschild spent four years interviewing people living and working near the polluted bayous near Lake Charles, Louisiana, who did not support greater environmental protections that could protect their health and safety. She asked “Why do working-class people support policies that liberals think hurt them?” which she described as the “Great Paradox.”

The people Hochschild talked with often sided with the chemical and oil companies that provided local jobs while also polluting homes and bayous. Their beliefs were based on an underlying “deep story” or resentment—but not toward the companies. Rather, people felt they had been marginalized by flat or falling wages, rapid demographic and social changes, and a liberal culture that often mocked their faith and patriotism and assumes they are racist and sexist. Put differently, liberal culture and politicians did not have a real understanding and “empathy” for the plight of the working class.

Working-class people and their communities are harmed by both environmental and economic injustices, and they have few economic choices. Solutions that might seem obvious, like ending the use of coal, can come with real costs—like loss of jobs.

As these examples suggest, creating blue-green alliances requires empathy rather than just judgments. It also helps to have a clear shared enemy. Steve Early describes this kind of alliance in Refinery Town: Big Oil, Big Money, and the Remaking of an American City. He writes about how workers, environmentalists, Latinos, African Americans, and some progressives in highly polluted Richmond, California, organized a blue-green alliance in response to a major refinery fire. They built a culture of resistance and forced Chevron to spend $1 billion to modernize a plant, making it safe and cleaner for the workers and community while saving jobs.

It was this attention to jobs, working conditions, and the environment that enabled the group to build a volunteer-driven political organization. When Chevron spent $3 million to try to get a new city council and a mayor elected (an amount unheard of in a local election), the blue-green coalition fought back, electing three environmental-friendly city council members and Richmond’s current mayor. As Early states, “It was a clear achievement for class-based community organizing around environmental issues and the importance of politics.”

But Early acknowledges that this type of blue-green organizing is not easy. In fact, a similar blue-green alliance formed after a refinery fire in Torrence, California, came apart when union members faced the threat of job losses. As Early notes, “job blackmail—and fear of job loss—remains a potent check on labor organization behavior involving workers engaged in the extraction, refining, transportation, or use of fossil fuel.” Tension over jobs creates real divides between unions and environmentalists.

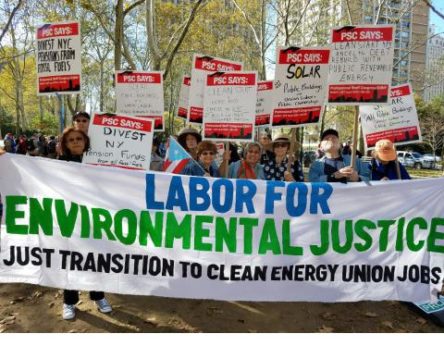

People have begun to take climate change and sustainability seriously, often with great empathy for working people. Interests and investments are growing for projects like the greening of buildings and cities, producing green products, and developing sustainable global production networks. Most of these are grassroots efforts, but larger groups and institutions are forming new national and international organizations that link environmental concerns with workplace and economic transformation.

For example, the ACW (Adapting Canadian Work and Workplaces to Respond to Climate Change) connects 25 partner organizations, including unions and environmental groups from seven countries, with 56 individual researchers working on opportunities and obstacles to create low-carbon adaptations for resources, manufacturing, construction, and services where worker agency, environmental concerns, and just transitions are all taken seriously. The model of just transitions emphasizes protecting and even improving workers’ livelihoods (health, skills, rights) as well as substantive community support.

Political leaders are just beginning to engage in this work, though the results so far are mixed. Democratic Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s Green New Deal (GND), a Congressional Resolution (not a bill), reimagines work in a period of climate change and a transforming economy. The GND offers an ambitious “vision statement” for a de-carbonization infrastructure, yet it also provides social protection as just transitions for displaced workers—training for green skills jobs within a broader social safety net. The GND drew howls from elected officials and industry lobbyists, who complained that it was too big, too fast, and impractical. Others suggested watered-down policies that undermined the GND but provided political cover for future elections.

While the House did not vote on GND, Senate Majority leader Mitch McConnell pressed for a vote in order to embarrass Democrats prior to 2020 elections. In the Senate, Republicans all voted against the resolution and most Democrats voted “present”—a display of the politics of evasion only slightly less dramatic than Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris Climate Accord. If this is how Democrats respond, why should anyone expect workers to be more receptive?

But there are signs of change, as some politicians are developing their own plans. In Los Angeles, Mayor Eric Garcetti has proposed his own Green New Deal, calling for the second-largest city in the country to have a carbon-neutral economy by 2050. Presidential candidate Beto O’Rourke has proposed new federal policies that would lead to net-zero emissions by 2050 and $5 trillion in spending over 10 years for investments in clean energy and extreme weather preparation.

Energy companies are even getting involved. Worried that they will not be able to control legislation, they are trying to demonstrate their commitment to the environment through family-friendly and alternative energy commercials touting their work addressing climate change. Yes, these same companies had rejected climate science for years. Some, like the Koch brothers, used their financial strength and political clout to disrupt the growing climate and workplace justice movements.

To build a just and inclusive movement to fight climate change and overcome past environmental classism, we need empathy, shared values, and organizing. This is what the Green New Deal promotes. In a short film about the resolution, Ocasio-Cortez imagines a green future that links carbon use with job guarantees that provide workers with good wages and benefits. But the GND’s most important contribution may be its call to build an environmental movement where no one is left behind.

This is an excerpted version of an article that originally appeared at the Working-Class Perspectives site, hosted by Georgetown University’s Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor.

Comments