**See below: “The making of a Communist” by Benjamin J. Davis **

This is the centennial of the birth of a former New York City Council member from Harlem and a remarkable African-American leader: Benjamin J. Davis.

Ben Davis was born Sept. 8, 1903, in Dawson, Ga. He grew up in a relatively privileged African American home. His father was the editor and publisher of the Atlanta Independent, a Black paper with a wide distribution throughout the South, and was also a member of the Republican National Committee.

Davis attended Morehouse College in Atlanta, then Amherst College in Massachusetts, where he secured his B.A. degree. From there he entered Harvard Law School, graduating in 1930 at the age of 27. Eminent scholar W.E.B. Du Bois, who knew him as a student activist at Morehouse, said Davis never thought of his own advancement as apart from that of his people and the working class.

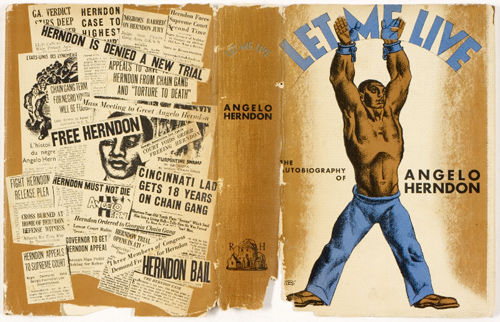

After finishing law school, in the midst of the Great Depression, Davis returned to Atlanta to practice law. One of his first cases was that of Angelo Herndon, African American leader of the local Young Communist League, who had organized a large hunger march of Black and white unemployed to Atlanta’s City Hall demanding jobs or bread. It was virtually illegal for Blacks and whites to march together. Seeing Blacks and whites united in struggle in the Jim Crow South around basic economic issues frightened the racist establishment. The police were ordered to stop the march, Herndon was roughed up, arrested and charged with insurrection based on an old statute left over from slavery.

The Herndon case, like the Scottsboro case, was shrouded in racism. It also raised the related issue of the right of working people to organize in defense of their class.

The International Labor Defense headed by William L. Patterson was called in to defend Herndon. When local racist establishment lawyers refused to take the case, young Ben Davis agreed to become Herndon’s attorney. Davis described the trial as a turning point in his life, saying, “In the course of trying that case I suffered some of the worst treatment along with my client, with the judge calling me ‘n——-’ and ‘darkie’ and threatening to jail me.”

Herndon was convicted, but the ongoing campaign of organizations like the ILD led to his early release from prison.

As a result of that experience, Davis joined the Communist Party. As he put it, “It required only a moment to join but my whole lifetime as an American Negro prepared me for that moment.”

Putting aside the pursuit of personal wealth and power, Davis dedicated his life to the liberation of his people.

In 1935 he moved to New York and became editor of the Negro Liberator, and later of the Party’s newspaper, the Daily Worker.

As Harlem organizer of the Party, Ben became a widely respected and popular figure. He led hundreds of actions against racism and discrimination, and helped build grass-roots coalitions with labor, churches, fraternal organizations, and tenants’ groups in Harlem. He worked closely with Rev. Adam Clayton Powell in many successful battles, including the “don’t buy where you can’t work” campaign to integrate the workforce on Harlem’s famed 125th Street, and the “pay your utility bill in pennies” campaign which forced Con Edison to hire Black workers. Through these experiences, Davis and Powell developed a strong friendship and mutual trust.

Davis was an internationalist who saw the struggle for the day-to-day needs of the African-American masses as linked to the struggle against imperialism and capitalism. He was an outspoken supporter of socialism and solidarity with the struggle for African liberation. He strongly supported the Soviet Union and recognized its role in the worldwide struggle for liberation. He won the respect and admiration of working people in Harlem because of his consistent commitment to freedom.

In 1943, after Powell was elected to Congress, Davis was elected to Powell’s City Council seat, becoming the second African American elected to the Council from Harlem. He was reelected in 1945 by a wider margin.

Powell enthusiastically backed Davis, saying in his endorsement statement, “Mr. Davis’ long record in the fight against discrimination and poll-taxes justifies his election. We have got to wipe Jim Crow out of New York City and Mr. Davis is the man to carry the fight where I left off in the City Council.”

In the City Council, along with his comrade Peter V. Cacchione, New York City councilman for the Borough of Brooklyn from 1942-1947, Davis waged many battles for justice for New York’s working people.

Long-time Harlem resident and close comrade and friend William L Patterson, of “We Charge Genocide” fame, said Davis saw his role “not to help the rich rob the poor,” but “to awaken the people as to what they had to do to see that the city’s slums were destroyed and that the Black ghettos, cursed with imposed vice, were turned into showplaces of pride and beauty.”

As a council member, Davis won passage of the first resolution declaring Feb. 13-19 Negro History Week. During his tenure he introduced 25 bills to protect African American rights, halt evictions, open new housing, protect tenants’ rights and stop police brutality. He opposed restrictive covenants in renting and construction of homes; fought for an end to racist jury selection; fought reduction of the West Indian immigration quota; called for legalization of rent strikes; and opposed the anti-labor Taft-Hartley law. He used the forum of the City Council to push for an end to the Cold War, colonialism and war.

When Davis ran for office he was supported by some of the most popular cultural figures of the day. Paul Robeson, Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, and pianist Teddy Wilson were among the sponsors of his victory reception. He was known to put on the best fundraising parties in Harlem. One was so large it had to be held in the Harlem Armory.

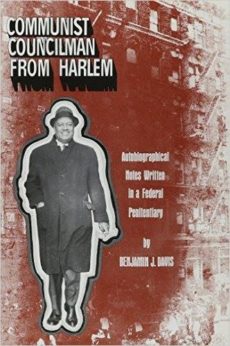

When the McCarthy period hit, Davis was a prime target. He was tried and imprisoned with 11 other Communist Party leaders under the infamous anti-Communist Smith Act, basically because of their political beliefs. Addressing the court after his conviction, Davis said, “The real crime committed is against peace, progress and democracy, against the working class, and my people, the Negro people.”

Davis served five years in federal prison and lost his council seat. This was a sad time for democratic rights, and a setback in the struggle for liberation, peace and social justice, especially for the people of Harlem.

After his release from prison, Davis resumed his political activities despite failing health. He and Gus Hall became the two national spokespersons of the Communist Party USA as the battle raged to defeat the remnants of McCarthyism. The repressive Smith and McCarran Acts, forerunners of today’s Patriot Act, were used against Communists and other progressives in the 1950s to crush dissent. The McCarran Act was later ruled unconstitutional, but great damage had been done not only to the Communist Party but also to the broad movements for economic, social and political justice.

In 1962 Davis made a national college speaking tour, drawing crowds at schools including Harvard, Columbia, Amherst, Oberlin and the University of Minnesota. Ironically, the City College of New York, in his old councilmanic district, barred Davis from speaking on its campus. After a student protest he spoke on the street.

Despite the government’s attempts to isolate and silence him, Davis retained considerable respect and influence in Harlem and in civil rights and labor circles across the country. As one of his last political efforts, he helped promote the 1963 March on Washington. He died on Aug. 22, 1964.

Ben Davis was a great revolutionary Black man, a man of the people, an inspiration to all who knew of him.

Every attempt has been made to erase his legacy from the collective memory of the people of Harlem and New York. Sad to say, there is no street, school or park that bears his name. That needs to be corrected.

In this centennial year of his birth we should celebrate the legacy of Benjamin J. Davis and the left and progressive democratic traditions of the African-American people in general and particularly the people of Harlem. We must continue his fight against war, racism, repression, unemployment and poverty.

*******

The making of a Communist

By Benjamin J. Davis

The following is an excerpt from Ben Davis’ speech to the Harvard Law Forum in 1962 on the subject of the repressive McCarran Act. The speech appears as an appendix to Davis’ autobiography, Communist Councilman from Harlem.

Do not think I feel like a stranger here. For Harvard has its progressive, even revolutionary traditions. There are, for example, John Reed, who wrote the immortal Ten Days that Shook the World, a description of the October revolution of 1917 that stands as a world-famous classic; and Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois, distinguished historian and scholar, a founder of the NAACP, who recently joined the U.S. Communist Party. Both these men studied at Harvard.

It may be of interest to you, as students here, to know how one who has had substantially similar educational experiences to your own became a Communist. I grew up in a typical Negro Republican home in the deep South. It was primarily my life as an American Negro in my country that prepared me for this political choice. The occasion was my serving as trial counsel in the Angelo Herndon case in my native home of Atlanta, Ga., in 1933. Since this case may be familiar in law curricula, it suffices to recall it briefly.

Herndon was an 18-year-old Negro youth charged with attempting to incite insurrection under an old Georgia statute of 1866. The maximum penalty was death, and he was mercifully sentenced to 20 years on the Georgia chain gang. He was later freed by a close vote of the U.S. Supreme Court. I was so outraged as a Negro, and partly by my Harvard idealism, that I volunteered my services in the case. The basis of the indictment was primarily his membership in the Communist Party and possession of Marxist literature, including copies of the Daily Worker. In the course of defending Herndon, I had to familiarize myself with these Marxist books. Their political philosophy in terms of my own status as a second-class citizen in my own country made more sense to me than anything I’d heard from the Republican and Democratic Parties. So I joined the Communist Party.

First credit for recruiting me goes not to the Communists but to the savage white supremacy assaults of the trial judge, Lee B. Wyatt, against all Negroes. Only secondarily does the credit go to the Communist Party which provided a rational, effective and principled path of activity and struggle through which the hideous Jim Crow system could be abolished forever in the U.S.

I cite this personal experience to demonstrate that the process through which I became a Communist was “Made in the USA,” not in Moscow nor in any foreign country. Socialism and Communism cannot be exported; they grow out of the conditions native to capitalist countries. And we Communists are ready to join with non-Communists and even anti-Communists in eliminating the very oppressive conditions under capitalism that result in people becoming Communists.

Yet, with it all, I am proud to be an American, proud to be a Negro, and proud to be a Communist!

And there is no contradiction between the three. I am proud to be an American because I have an abiding confidence in the creative capacity of the American people to set our country right in all respects and keep it so, and to move it to higher levels of happiness and peace.

Comments