The indignity with which the Indigenous people are being treated in the COVID-19 pandemic opened a new and appalling chapter in the Brazilian government’s violation of the rights of its original inhabitants.

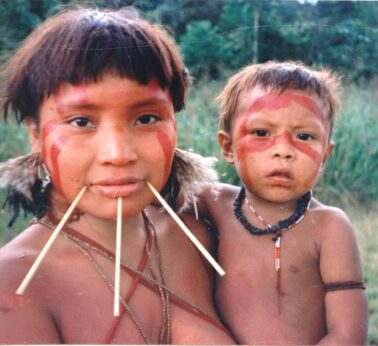

Three women are living a nightmare for which it will be necessary to invent a name. They are Sanömas, part of the Yanomami ethnic group, and their village, Auaris, is part of what white people know as the Brazilian state of Roraima, which borders Venezuela. But the Yanomami do not know the meaning of “borders”—for them, it is a fenceless land. They speak their own language, not Portuguese. In May, three Sanöma mothers and their infants were flown to Boa Vista, Roraima’s capital. The babies had pneumonia-like symptoms. In the hospital, the children may have contracted COVID-19. They died and their small bodies disappeared, perhaps interred in the municipal cemetery. Two of the mothers have COVID-19. They are part of the crush at the Indigenous Health House (CASAI), currently packed with sick people. There, ravaged by the virus, they beg for the bodies of their babies.

With the help of various people, one of the mothers sent me a message, written in Sanöma dialect: “I suffered to have this child. And I am suffering. My people are suffering. I must bring my child’s body back to the village. I cannot return without my child’s body.” I listen to the message read before it is translated into Portuguese. I cannot understand the words but I understand the terror, the universal language of something being wrenched from the world of human beings.

To be torn from a village in the interior of the Amazon rainforest because your child has symptoms of pneumonia, a disease transmitted by the first white men who decimated part of the Yanomami population in the previous century, is a violent act. To pass from this world into a hospital space, and in a hospital overcrowded because of COVID-19, is another act of violence. To have your baby contaminated by a second illness while it was hospitalized for a still hypothetical first one is yet another violence.

And then she loses the child. Each of them loses her child.

The Sanöma mothers don’t understand Portuguese. Roraima is the Brazilian state with the most Indigenous people and, in spite of the fact that nearly 200 Yanomami residing there have been infected with COVID-19, there is not one translator available. So no one explains anything to anyone and the women have no idea what people are talking about. They understand only that their babies have perished and their corpses have disappeared. One of the community leaders understands Portuguese. He explains that the three babies may have been interred in the cemetery. But that is not certain. No one gives the Indigenous mothers or their leaders any assurance.

Alisson Marugal, the federal prosecutor in Boa Vista, sent an official letter to the Yanomami Special Indigenous Health District (DSEI-Y) to obtain information about the supposed whereabouts of the babies’ bodies. “The situation is very complicated, especially in relation to the Yanomami population. We had four official deaths and there were problems with all of them. The first was the case of a 15-year-old adolescent male. We had problems regarding his medical care, there was a lack of information. We are also checking to see if there was a failure [to provide] medical help,” Marugal says. “We are just beginning to verify the case of the Sanöma babies now. We don’t know if there was a diagnosis of COVID-19 and, if so, what protocol was applied and what was the interment site.”

Marugal assumed his post in the middle of the pandemic; he tells of working from second to second to get a handle on a very challenging situation. “I do not rule out the possibility of publicly filing a civil legal action asking for moral damages not just for the babies’ parents, but for all Yanomamis.”

To bury a Yanomami’s body is to tear it from the world of the humans

The violence inherent in this series of aggressive acts against Sanöma women is enormous even for the long-established patterns of the Brazilian State, a historic agent of aggression against its Indigenous peoples. But there is another even more violent cultural difference. While many non-Indigenous families are suffering because they cannot mourn their loved ones or even attend their funerals due to pandemic and biosafety protocols, for the Yanomami the act of burial itself is both incomprehensible and unacceptable.

Yanomami people are never, under any circumstances, buried. Their bodies are cremated, and there is a lengthy ritual to assure they die for themselves and for the community. The Yanomami are not individuals, like white people who live in Brazil or in Spain or in the United States. A Yanomami is part of a community that is interlaced with various dimensions of visible and invisible worlds in relationships mediated by shamans. Death rituals must be followed in every detail and may take months or even years to complete. Various villages travel to the community of the deceased to play a part in the rites of cremation. Thus, the ashes are protected.

Months later, there will be a second stage, when the visitors return again for celebrations. Now the deceased will be remembered for their deeds, for their quarrels, for all the things that make their trajectories distinctive. They will be remembered so that then they can be forgotten, their traces will be erased and the community can move forward. In a final act, the dead one’s ashes are diluted in a banana porridge and ingested so that the body of the deceased is dispersed through the body of the community.

This ritual allows the memory of the dead person to die as well so that his or her survivors can get on with their lives. If the rites are not duly celebrated, the dead cannot forget or be forgotten, which burdens their relatives and their community. The mortal rites of the Yanomami are both wise and complex. The fact that they are collective celebrations provides an occasion for establishing sociopolitical and amorous relations. The only dead person is the one who died. The living do not indulge in continuous bereavement as often happens in the white world where people have neither time nor space to mourn and separate from their loved ones.

To bury a corpse is an absolute horror for the Yanomami. It is like wrenching or tearing someone away from the world of the humans. “For these mothers to know that their children are interred in a municipal cemetery is the equivalent of a white woman having to live with the idea that her child’s body has been left exposed in a public place for all to see,” says Sílvia Guimarães, professor of anthropology at the University of Brasília (UnB), who has been conducting research alongside the Sanöma people for many years. She is one of 40 researchers and supporters of the Pro-Yanomami and Ye’kwana Network, formed to confront the media invisibility of Yanomami suffering during the pandemic by divulging qualified analyses.

Without an emergency plan, 40% of the Yanomami people may have the virus

The Yanomami Indigenous Territory occupies around nine and a half million hectares in the States of Amazonas and Roraima on the Brazil-Venezuela border. More than 300 villages are inhabited by more than 26,000 Indigenous people. The Sanöma subgroup is composed of 3,164 people, according to 2018 data supplied by the Socio-Environmental Institute (IS). Some groups live in voluntary isolation because they prefer not to live with or near white people. Since 1910, when the first contacts between the Yanomami and invasive gold prospectors took place, the Indigenous people have been decimated by shootings and what they call xawara, communicable plagues.

Davi Kopenawa, recognized as an intellectual and a Yanomami leader, has warned the world that his people run the risk of genocide. He calls whites “the merchandise people.” His son Dario Kopenawa, head of the Yanomami Association Hutukara, launched the “Fora Garimpo! Fora COVID!” (Out Prospectors! Out COVID!) campaign. Even during a rampant pandemic, more than 20,000 riverine gold prospectors remain on Yanomami territory, making it the Amazon’s most vulnerable to this new strain of coronavirus. Research conducted by the Federal University of Minas Gerais, the Socio-Environmental Institute, and the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation predicts that, unless what is now a “contingent” emergency plan is put into effect to prevent transmission of COVID-19 among the Yanomami, the 40% of the population that lives in villages proximate to gold-panning sites will be contaminated.

So far, according to a bulletin from The Pro-Yanomami and Ye’kwana Network, dated June 21, there have been 168 cases of COVID-19 and five deaths. The Indigenous Health House (CASAI), where all Yanomami brought to Boa Vista are interned, has become one of the principal sites of contamination. According to the researchers’ network, more than 80 Indigenous people have already been infected there, representing 48% of the Yanomami and Ye’kwana COVID-19 cases. There are Yanomami patients with other diseases who were discharged, have been waiting for more than two months to return to the Indigenous Territory, and were infected with the new coronavirus while in the CASAI.

Ever since the first adolescent Yanomami, a 15-year-old boy, died of COVID-19 on April 9, their desperation has multiplied. To the victims of a multitude of massacres at the hands of white men, that another, unprecedented kind has appeared seems impossible. But there is always something. The Yanomami began to see their bodies disappearing, followed by vague explanations of interments from authorities they could scarcely understand. “This is an enormous lack of respect for our culture. Infant bodies are buried without explanation, family members are not consulted, mother’s permission is not requested. No one has any idea where their children’s bodies are,” Dario Kopenawa complains. “We want to know where they are and when we can take them back to the villages where they were born and raised, where their parents, their uncles, and aunts, their cousins are living, where their souls can rejoice. We understand the need for biosafety procedures, but we must have information and understand when and what is going to happen. We need to know when the bodies will be returned. We want to know how long the virus stays in a body. If the infectious disease experts explain these things to us, we will understand and respect them. Then we can transmit the information to our communities.”

The biosafety protocol, according to The Pro-Yanomami and Ye’kwana Network, requires three years before a body is exhumed but up to now, there is no proof that these children even had the disease.

“Why three years? Why not more? Why not less? Who is going to explain this to the Yanomami women?” asks Sílvia Guimarães in an EL PAÍS interview.

Braulina Baniwa is one of the Indigenous women who, although she belongs to another ethnic group, states her solidarity with the Sanöma mothers: “These women are suffering from a measureless violence. A part of each of them is going to remain outside the territory. They don’t speak Portuguese and no one cares to understand them.” An anthropologist, she works with the Matula Laboratory’s “Sociabilities, Differences and Inequalities” study group, an offshoot of the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development.

Here is a passage from a Matula public letter: “We believe that the human rights of these Sanöma women, left without the bodies of their babies and voiceless about how those infant lives should be remembered, have been violated and that this exposes the pain of Indigenous women in this pandemic. The scenario is repeated in various Brazilian locales. How heavy must it be when someone who does not speak Portuguese is removed from the support of her people and is waiting to hear if she has contracted the virus? What is the possibility of having her words heard, of having her experience with death shared and resolved? We agree that there are multiple shapes this contagion can take, all of them risky, but there are still some questions we must ask. ‘Is it possible to be transparent? Can we have open discussions? How can we share Indigenous knowledge and decisions? What ethical criteria will we live by in this pandemic?’ This pandemic lays open to the world the range and dimension of social inequities that have been ‘normalized.’ All public service infrastructure has been erased for this parcel of the population, so the risk of mortality for Indigenous mothers and their children grows increasingly dire. Complete paralysis in regard to proactivity is the rule. The Sanöma women embody the strength of all Indigenous women, of their Territory, of the forest that needs to be constantly cleared and planted with food, of the rivers they fish, of all that they deal with to survive. They deserve respect, care, and admiration from the [Brazilian] State.”

The Yanomami leaders demand an Indigenous protocol for those killed by COVID-19. “We want the bodies to be hygienically treated and, if this is impossible, we want them to be cremated. Then we will be able to take the ashes back to the villages,” says Dario Kopenawa. There is no crematorium in Boa Vista, Roraima’s capital. And there also seems to be no desire to understand or sympathize with the plight of the Indigenous people in a society where racism against [the continent’s] original inhabitants reigns supreme. What were once millions are now just 896,917 people, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics 2010 census. This number represents 0.47% of Brazil’s total population. Yet their cultural wealth is expressed in more than 150 languages spoken by 256 distinct peoples. Decimated by five centuries of viruses and bullets, they are the last survivors and continue to resist extinction. And along comes COVID-19. One of the main goals of the Bolsonaro government is to open the Indigenous Territories to private investment. This has done nothing to contain the plague that has already crossed the Amazon rainforest, producing a new massacre.

According to Dario Kopenawa, the Yanomami have been infected with COVID-19 by gold prospectors who invade their lands with impunity. In Boa Vista, these prospectors not only circulate freely, they are acknowledged by the public who have erected a public monument. That they are exalted as pioneers expresses the tension between the original peoples and white men who were initially brought there to work on State projects and afterward stayed or came on their own.

“Long before the pandemic, we had the prospector illness, our rivers are polluted with mercury, our people die of tuberculosis and pneumonia. Now they have brought us COVID-19 as well,” says Dario Kopenawa. Due to the prospectors’ continued intrusion, malaria is also spreading among Indigenous people throughout the Territory. “Now they are burying us,” Dario continues. “Before, no Yanomami was ever buried. Never! Yes, I think it is violence. And I think that doing it without consulting us or asking our permission constitutes a crime.”

When he heard about the theme of this report, Antonio Pereira, coordinator pro tem of the Special Yanomami Indigenous Health District (DSEI), called EL PAÍS to explain that he could not respond to questions because he was in a meeting. He agreed to contact this reporter when the meeting was over. When she insisted that they agree on a time to converse, Pereira passed the phone to an assistant who said they would call. It was not possible to reestablish contact with Senhor Pereira, the man in charge of Yanomami Health, before this article went to press.

The baby was born, died, and disappeared

There is another Yanomami woman, stricken with coronavirus, who was brought to the hospital to give birth and never saw her baby’s body. The newborn, according to Alisson Marugal, Roraima’s state prosecutor, died of complications unconnected to COVID-19, but a hospital employee inappropriately wrote that coronavirus was suspected on an official document. According to information obtained by EL PAÍS, the infant’s family belongs to another Yanomami group that lives in the Nara Uhi village, not far from the Catrimani mission. Born seven months premature on April 28, the infant, a male, died the same day. His body is unaccounted for.

The infant’s father’s account to The Pro-Yanomami and Ye’kwana Network points to the fact that the virus has begun to decimate the Yanomami people and that the [Brazilian] State has become a perpetuator of violence that produces new sufferings. This Yanomami man is known to the local whites as “Remo” [perhaps because he rents his canoe: the English word for remo is oar—translator’s note]:

“This is how it happened. First, the shaman, André, showed signs of COVID. He is an older person and was the first to get sick. Then Miguel, his son, tried to heal his father as a shaman and got sick too. The day after Miguel began to feel bad, he walked to the health post at the Catrimani mission. The third person in our community who got sick was my wife, Zita Rosinete. She was pregnant. She had cough, diarrhea, fever, headache, chest pains, and a big pain in her belly. The shamans did not work with her because they were afraid they would get sick, as COVID is so strong.

“The next day, I took Zita Rosinete to the Mission health post. She collapsed three times on the path. She was very weak with lots of fever. I was very unhappy there. On April 27, we were taken by airplane from the Catrimani mission to the Boa Vista maternity ward. When we got to the hospital, Rosinete fainted again while I was carrying her. So maybe COVID got inside of me. But when they tested me through my nose and through my mouth, I was negative. [Later, Remo tested positive for COVID-19 at CASAI, the ‘House of Indigenous Health.’] My wife was having a lot of difficulty breathing. She was so weak she almost died! I asked the doctor, ‘Is she going to die?’ He said, ‘No, she is still a little strong on the inside.’ In the maternity ward, we slept separately from other people.

“My son died. On the 28th [of April], the same day he was born, he died. He was born in the morning and died in the afternoon. Zita Rosinete was still very weak, but a little stronger, because she did not want to die. If she had thought about dying, she would have died.

“I did not see my son. When Zita Rosinete gave birth to the baby, the doctors said, ‘Take him to the hospital, to the ICU.’ Then he died. I was very sad. I am still sad. The doctor did not say why he died. He said, ‘Hey, are you the father?’ Yes, I am the father.’ ‘I’m sorry, your son is dead. He had trouble breathing before he died.’

“I think he died at 2 pm but I am not sure…they wrote it on a paper. I said to the man nurse, ‘I want to visit my son!’ He said, ‘Wait a while. The doctors are still examining him.’ So I waited and waited and waited and later the information came: ‘Your son died today.’ The body, it may still be there, in the ICU. I do not know where it is. In the CASAI they did not say where my son’s body is. They have no information about it at all. I have a paper (Declaration of Live Birth) that talks about my son. At the CASAI, a woman nurse asked, ‘Where is your son?’ I said: ‘He died!’ ‘Where is the document saying that he died in the maternity hospital on the day of the 28th?’ ‘I do not know. The doctors did not give it to me.’”

Remo and Rosinete only returned to their village on June 19, without their son’s body. This is an example of another violent rift with the Yanomami people. The Federal Public Ministry is investigating this case and also that of other adults who died and whose bodies are claimed by the Yanomami.

“To steal someone else’s dead is the supreme stage of barbarism”

The French anthropologist Bruce Albert compares “the secret and compulsory (‘bio-secure!’)” internment of the Yanomami victims of COVID-19 to the “disappearance” of the bodies of the victims of the torturers during the military dictatorship (1964-1985). “To steal someone else’s dead and deny their bereavement was always the supreme stage of barbarism, in its contempt and its negation of the ethnic and/or political Other,” Dr. Albert stated in an EL PAÍS interview. Dr. Albert and Davi Kopenawa co-authored a landmark book in the history of anthropology: A queda do céu [The Sky is Falling], published in Portuguese by Companhia das Letras.

In 1993, the episode known as “the Haximu Massacre” in which prospectors assassinated 16 Indigenous people, demonstrated how important funereal rites are to the Yanomami. “Although terrified of being hunted down by the prospectors, they did not hesitate to risk their lives to retrieve, mourn and cremate their dead even while on their escape route,” Dr. Albert recalls. “The Yanomami would rather die than leave the dead unremembered.”

In past battles, the Yanomami always declared a truce so that their enemies’ women could retrieve their bodies from the forest and mourn them as is their custom. To make dead enemies “disappear,” the anthropologist claims, was considered “a dishonorable and, literally, inhuman manifestation of hostility: an action they ascribe only to wild beasts or maleficent forest spirits.”

After our interview was over, Dr. Albert said, “I hope what I said convinces your readers that there is no greater affront and cause for suffering among the Yanomami than the ‘disappearance’ of their loved ones.”

The case of the Sanöma babies opens another chapter of State violence against the aboriginal inhabitants of what is now Brazil. The public authorities deal with death with the same disrespect and indignity with which they deal with life. It is not enough to be killed en masse by viral infection—the survivors, men and women both, are tortured. This chapter is just beginning, but the victims have already given it a title—genocide.

This article originally appeared (in Portuguese) in EL PAÍS Brasil. The English translation for People’s World is by Peter Lownds.