WASHINGTON—Short-staffing. Temp nurses hired off the street who are more interested in paychecks than patients. No N95 masks for months. Arbitrary management decisions with workers and their union cut out of the loop. No input on how to improve the medical care for the nation’s veterans.

Welcome to the latest description, courtesy of its Government Employees local union leaders, of the sad state of affairs in the Department of Veterans Affairs’ hospital system, the largest such chain in the U.S. Other problems join those listed above. And all of this hurts veterans’ care, those local leaders told a Dec. 16 press conference.

Outgoing Republican Oval Office occupant Donald Trump has only worsened things with his anti-worker dictates, designed to destroy both the two million federal workers who toil for his government and their unions, said one local leader in describing efforts to fight back against the ills.

“It’s like going against the entire U.S. Army with only a handgun,” Marcellus Shields of the union local at VA’s Wilmington, N.C., hospital, explained.

The mess at the VA “is not just about our numbers. This is about the veterans,” Shields added, pleading with reporters to tell the real story at the VA because the agency brass isn’t. “Everyone here is tired of beating our head against the wall.”

VA, second only to the Pentagon in numbers of federal workers, serves nine million veterans. It boasts of the quality of its care and veterans groups generally laud it, too.

Veterans and their groups also overwhelmingly don’t want it privatized or be forced to visit private clinics and thus be deprived of the expertise of VA physicians and nurses who have learned how to treat the whole veteran and all his or her ills, not just one disorder each.

Those injured vets range from soldiers left limbless due to improvised explosive devices—bombs—from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars to PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) sufferers from their service ranging back to the Indochina and Korean Wars.

The VA itself has been under stress, following a scandal, reported first by AFGE whistleblowers, showing bosses falsified records to hide lack of care or slow care at many of its hospitals. The bosses both covered up and retaliated against the whistleblowers.

Congress, under the guise of “reform,” responded by making it easier to fire workers and bosses, in two laws enacted since that scandal. The laws also let VA pay private doctors who treated vets who were not close to VA hospitals or clinics.

That subsidy to non-VA docs was a Trump regime step towards privatizing the VA, the Government Employees said then. So did vets groups. Congress’s ruling Republicans brushed them off, as Trump installed pro-privatization ideologues in top VA management posts in D.C.

Trump also took away ways to fight back. His executive orders stripped federal workers in general of due process rights against arbitrary discipline. And stripped unions of ways to communicate with members and have dialogue with bosses, workers said. Though they didn’t say so, one Trump executive order also bans rank-and-file workers from contacting Congress.

And then the coronavirus lowered the boom. VA facilities then had 50,000 worker vacancies nationwide. “We had a skeleton crew already, and then the pandemic hit,” said Regina Smith of Local 424 at the Baltimore VA Hospital.

“A lot of nurses are fatigued and strained and stressed due to all the overtime” bosses demand, as a result, said Scott Geddes, President of Local 1891, who represents workers at VA’s Community Living Centers in Queens, Manhattan and the Bronx.

Overtime estimates ranged from 12 hours daily seven days a week in the Bronx to “17-18 hours a day,” including regular non-overtime shifts, at VA’s Milwaukee hospital, said Gayle Griffin, president of Local 3 there. Geddes said workers “were never made whole” for the extra hours. Griffin noted “people were disciplined if they didn’t work” such long hours.

To ease the short-staffing and “keep our patients safe, we suggested managers and assistant managers take part in patient care,” added Barbara Calle, a 30-year veteran nurse at the Minneapolis VA Hospital. “We were told ‘We don’t.’”

Contracting-out is rampant and rising. “Contract nurses make three times what we make and care only for the money. They’re not there every day, and” unlike the VA’s own nurses, “are not vested in the vets,” said Scott. Added Griffin: “Now, they’ll be contracting out not just nurses but Certified Nursing Assistants” according to a fellow local officer who called her.

Favoritism, racial and otherwise, comes into play when bosses distribute bonuses, several workers said. “They give performance awards of $3,000 or so to people who aren’t even treating patients, while the nurses get $250,” Scott said of area bosses. Baltimore’s Smith, who is Black, reported “people at the lower end of the pay scale,” like food service workers, aren’t getting bonuses. They’re typically workers of color.

“There’s a real disparity. I first asked about it on June 12, and I haven’t gotten an answer. I’ll give them two more months and then file a ULP [unfair labor practices] charge if they don’t.”

Meanwhile, VA hired 10,000 people systemwide, reported Calle. They’re all supervisors. The agency has given no racial breakdown of the new hires.

Staff shortages are not new, but now they’re really bad, adds Baltimore’s Smith. “In 1993, when I was hired, we had adequate staff.” There have been shortages before “but this is the worst and highest evil since I’ve been here. As a result, people have died.”

There’s also little protection for workers against the coronavirus’s ravages. One worker described being told to wear bandannas due to a lack of N95 masks. Others fear that lack of protective gear and social distancing means they could catch the virus and infect their families.

Jim Rihel of Local 940, which represents workers at the VA Benefits Center in Philadelphia, the agency’s largest, says it’s “three or four stories” high with “300 to 400 people per floor where we can’t socially distance” for protection against the coronavirus’s spread.

“Since March, there have been four” positive cases “in a closed building and they’ve deep-cleaned it only once,” he notes.

“Our people are getting hand wipes for 12- to 14-hour shifts. And they’re being required to wear one surgical mask, not an N95 mask,” for that entire time, added Minneapolis’s Calle.

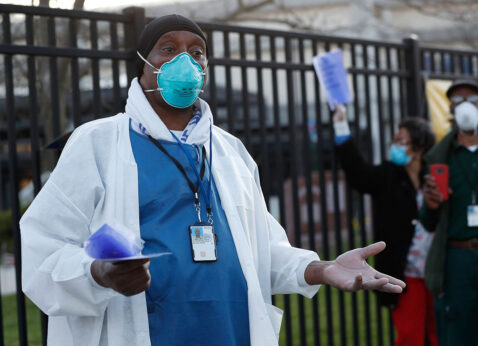

AFGE isn’t the only union upset by VA’s mismanagement during the Trump regime’s reign. National Nurses United, whose members include RNs at VA hospitals around the U.S., have been raising a ruckus about short-staffing literally for years, even before the scandals.

The pandemic only worsened things, forcing the RNs to hit the streets in public protests. The latest was at the Rocky Mountain VA Medical Center in Aurora, Colo., on Nov. 19.

There, VA bosses have done nothing about chronic short-staffing, instituted widespread shift changes the day before, and wrote up a nurse who hung flyers about what was going in on employee-only areas of the hospital. The union contract allows such flyers.

“We are alarmed to see the flagrant disrespect, intimidation, and disregard for our union rights,” said Sharda Fornnarino, RN, in a statement before the Colorado protest. “No nurse should be pulled away from their patients, detained, and cited for exercising their rights.”

“Furthermore, we understand there are times when changes must be made in the hospital. We do not have an issue with change, but we have an issue with being excluded in the discussions and decision-making about our working conditions, a bargained right, which is guaranteed by our contract.”

In his last statement on both VA staffing and anti-virus supplies, in May, Trump VA Secretary Robert Wilkie claimed there were no problems. But he has another problem himself.

VA’s Inspector General reported Wilkie intentionally disparaged a female congressional aide after she reported a sexual assault at the VA hospital in D.C. The six biggest vets groups and the House’s top two Democrats now demand Trump fire Wilkie, who denies the charge.

In May, Wilkie said VA had enough beds for veterans and enough staff to handle coronavirus-hit vets, too. One way it freed up room, he said, was to defer elective surgeries in favor of coronavirus care. He didn’t define “elective,” but said that freed up some 4,000 beds.

He also said that as of April 28, VA had hired “9,338 medical staff” but only 2,147 were full-time nurses. He didn’t give a breakdown of other hires. He said VA bought 4.5 million N95 masks from New Hampshire then and has “millions on hand.” Wilkie didn’t give a number.