People’s World is happy to reprint below an article from the Feb. 15, 1945 issue of the Daily Worker by W. Alphaeus Hunton, then the educational director of the Council on African Affairs (CAA).

Hunton, considered “one of the most neglected African American intellectuals” in U.S. history, partly due to his membership in the Communist Party USA, worked closely with Paul Robeson and W.E.B. DuBois domestically and internationally. Through the CAA, he helped to build a transatlantic alliance that fostered solidarity between African Americans fighting for equality and Africans fighting for liberation against colonial subjugation and oppression.

In the column below, written during “Negro History Week,” Hunton highlights internationalism as a key strategy African Americans and Africans have deployed repeatedly against slavery and white supremacy, as well as colonialism abroad. He also merges the World War II Allied fight against fascism with the fight against racism and colonialism, and notes that African Americans and colonial peoples have an opportunity—with the war nearing its end—to push the Allied powers to fulfill the promises made as part of their war-time alliance, through, for example, the Atlantic Charter.

Next week, People’s World will reprint another column by Hunton, as well as a brief sketch of his life and work by Tony Pecinovsky, who is completing a book about Hunton to be published later this year titled The Cancer of Colonialism: W. Alphaeus Hunton, Black Liberation, and the Daily Worker, 1944-1946.

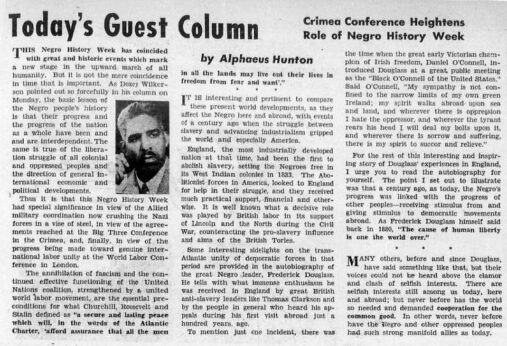

“Today’s Guest Column: Crimea Conference Heightens Role of Negro History Week,” Daily Worker, February 15, 1945.

By Alphaeus Hunton

This Negro History Week has coincided with great and historic events which mark a new stage in the upward march of all humanity. But it is not the mere coincidence in time that is important. As [fellow African-American Communist Party leader] Doxey Wilkerson pointed out so forcefully in his column on Monday, the basic lesson of the Negro people’s history is that their progress and the progress of the nation as a whole have been and are interdependent. The same is true of the liberation struggle of all colonial and oppressed peoples and the direction of general international economic and political developments.

Thus it is that this Negro History Week had special significance in view of the Allied military coordination now crushing the Nazi forces in a vise of steel, in view of the agreements reached at the Big Three Conference in the Crimea, and, finally, in view of the progress being made toward genuine international labor unity at the World Labor Conference in London.

The annihilation of fascism and the continued effective functioning of the United Nations coalition, strengthened by a united world labor movement, are the essential preconditions for what Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin defined as “a secure and lasting peace which will, in the words of the Atlantic Charter, ‘afford assurance that all the men in all the lands may live out their lives in freedom from fear and want.”

It is interesting and pertinent to compare these present world developments, as they affect the Negro here and abroad, with events of a century ago when the struggle between slavery and advancing industrialism gripped the world and especially America.

England, the most industrially developed nation at that time, had been the first to abolish slavery, setting the Negroes free in its West Indian colonies in 1833. The Abolitionist forces in America looked to England for help in their struggle, and they received much practical support, financial and otherwise. It is well known what a decisive role was played by British labor in its support of Lincoln and the North during the Civil War, counteracting the pro-slavery influence and aims of the British Tories.

Some interesting sidelights on the trans-Atlantic unity of democratic forces in that period are provided in the autobiography of the great Negro leader, Frederick Douglass. He tells with what immense enthusiasm he was received in England by great British anti-slavery leaders like Thomas Clarkson and by the people in general who heard his appeals during his first visit abroad just a hundred years ago.

To mention just one incident, there was the time when the great early Victorian champion of Irish freedom, Daniel O’Connell, introduced Douglass at a great public meeting as the “Black O’Connell of the United States.” Said O’Connell, “My sympathy is not confined to the narrow limits of my own green Ireland; my spirit walks abroad upon sea and land, and wherever there is oppression I hate the oppressor, and wherever the tyrant rears his head I will deal my bolts upon it, and wherever there is sorrow and suffering, there is my spirit to succor and relieve.”

For the rest of this interesting and inspiring story of Douglass’ experiences in England, I urge you to read the autobiography for yourself. The point I set out to illustrate was that a century ago, as today, the Negro’s progress was linked with the progress of other peoples—receiving stimulus from and giving stimulus to democratic movements abroad. As Frederick Douglass himself said back in 1880, “The cause of human liberty is one the world over.”

Many others, before and since Douglass, have said something like that, but their voices could not be heard above the clamor and clash of selfish interests. There are selfish interests still among us today, here and abroad; but never before has the world so needed and demanded cooperation for the common good. In other words, never before have the Negro and other oppressed peoples had such strong manifold allies as today.