In a November 1950 article in Paul Robeson’s newspaper Freedom, the scholar-activist Alphaeus Hunton noted that “the most reactionary minority of the American people,” the U.S. ruling class, “has advanced from its role of silent partner of the Western European imperialist powers.” No longer “content with arming and financing their wars against the colonial revolutionaries,” the ruling class now sought “aggressive leadership and active participation in those wars,” a decision that would lead to tens of millions of deaths.

Hunton’s insightful prognosis was born of decades of research, activism, and contact with leaders of anti-colonial movements. As an architect of the early struggle for African-American equality and Black liberation in Africa, Hunton’s life was committed to exposing the links between domestic racism and Jim Crow, and colonialism and imperialism abroad.

Alphaeus Hunton was born in Atlanta, Georgia, on September 18, 1903. He was a scholar, political activist, and life-long member of the Communist Party USA. While still young, his family moved to Brooklyn, where he finished high school. He attended college at Howard and Harvard universities. Afterward, he taught English at Howard and led the effort to organize the university’s faculty into the American Federation of Teachers Local 440.

By the mid-1930s, Hunton had become a fixture among Washington, D.C.’s Black left. After the formation of the National Negro Congress—perhaps the most important Communist-led Popular Front organization of the era—Hunton quickly ascended to NNC leadership, as a member of its national executive board, as a leader of the D.C. chapter, and as chair of its labor committee. He also joined the editorial board of the NNC’s journal, Congress View. It is around this time that he officially joined the CPUSA.

During this time—like the Black Lives Matter movement today—protests against police violence were a daily occurrence in D.C. To Hunton, “Washington sets the pattern of discrimination against the Negro people.” Its laws “establish the nation’s unwritten laws by unofficial endorsement of, or passive indifference to practices of discrimination, segregation, and brutal oppression.”

According to Erik S. Gellman, in Death Blow to Jim Crow: The National Negro Congress and the Rise of Militant Civil Rights, Hunton “played an essential behind-the-scenes role in the police brutality campaign.”

Throughout the NNC’s existence, Hunton would play a leadership role focused on building unity against racist oppression. The NNC and the Southern Negro Youth Congress, often in alliance with CPUSA activists and CIO organizers, also helped to build unions among African Americans.

In 1943, Hunton left Howard University and accepted a position as education director of the Council on African Affairs, which sought to build cross-Atlantic alliances between African Americans fighting for equality and Africans fighting for liberation against colonialism.

During World War II and the immediate post-war period, the CAA was part of “a second incarnation” of the Communist-led Popular Front, which endured through the early Cold War. In a climate of increasing political repression, the CAA unapologetically fused anti-colonial and pro-Soviet sentiments domestically, a perspective held by its principal leaders—Hunton, Paul Robeson, and later W.E.B. DuBois—a perspective at odds with U.S. imperialism.

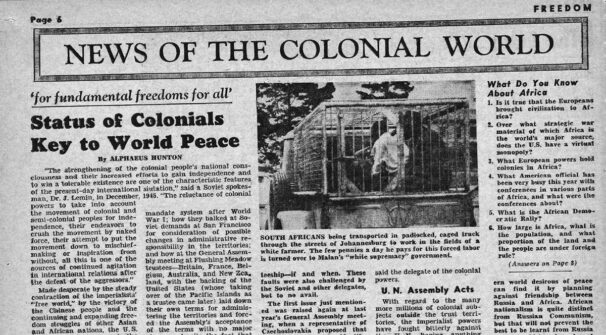

As editor of the CAA’s publications, New Africa and later Spotlight on Africa, and through countless articles—in the Daily Worker and Freedom, for example—pamphlets and booklets distributed globally, Hunton promoted solidarity with African anti-colonial movements and their leaders. Hunton provided content and analysis “to 62 foreign papers and 67 U.S. newspapers.” As he noted, the CAA’s “prime objective was the provide a sound basis of accurate information so that the American people might play their proper part in the struggle for African freedom.”

The CAA fought against racist apartheid and starvation in South Africa, defying the prevailing winds of Red Scare by, for example, organizing a 5,000-person rally in April 1952 that featured Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. (D-N.Y.) to coincide with the African National Congress’s Defiance Campaign. After the rally, the CAA picketed the South African consulate for 30 hours and started a petition drive in support of the ANC with a goal of collecting 100,000 signatures. Hunton called for “redoubled efforts…to broaden the petition drive [and] translate into concrete and effective action the widespread bitterness and indignation of Americans, particularly Black Americans, over the rampant racist barbarism” in South Africa.

For its cross-Atlantic solidarity with the ANC, the CAA and its leaders would be endlessly hounded, harassed, and, in Hunton’s case, thrown in jail for refusing to divulge names of donors to the Civil Rights Congress bail fund, which he served as a trustee.

Labeled “subversive” by the House Un-American Activities Committee, by 1955 the CAA would be forced to dissolve.

Like his mentors and friends Robeson and DuBois, Hunton continued his work on behalf of Black liberation and socialism. In 1957, he published Decision in Africa: Sources of Current Conflict. In it review, the Pittsburgh Courier noted, Hunton painted “a sorry picture of a continent being systematically and ruthlessly robbed,” and added, “it is difficult if not impossible to controvert Mr. Hunton’s thesis.”

Though largely ignored domestically, the book was eventually translated into dozens of languages, and Hunton was asked to lecture throughout the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, and the newly decolonizing nations of Africa.

In 1960, Hunton accepted a teaching position in Guinea. However, by 1962 he would accept DuBois’s invitation to relocate to Ghana to help work on the Encyclopedia Africana. Due to DuBois’s worsening health—he would pass in August 1963—Hunton eventually took over the Encyclopedia as its Secretariat, and “built the conceptual, human and material framework” for the projected 10-volume project. Also during this time, Hunton wrote regularly for Freedomways, the quarterly journal of Black liberation.

Hunton would continue working on the Encyclopedia until early 1966 when a coup ousted his patron Kwame Nkrumah, the charismatic socialist first president of independent Ghana. Soon, Hunton and his wife Dorothy were unceremoniously deported. Though his expulsion was “unnerving and humiliating,” Hunton told the New York Times, he was still optimistic, as the Encyclopedia “was a pan-African project, not a Ghanaian one,” on which he hoped to continue working.

In early 1967, Zambian president Kenneth Kaunda invited Hunton to that country as his guest. He worked on a history of the nationalist movement and wrote a column for Mayibye, the underground bulletin of the ANC, thereby bringing full-circle a political commitment given substance 30 years earlier with Hunton’s work in the NNC.

Hunton passed away on January 13, 1970, in Lusaka, Zambia. Kenneth Kaunda wept at his graveside.

Throughout his life, Hunton was unapologetic in his commitment to African-American equality, Black liberation, and socialism. He saw colonialism and imperialism as an extension of domestic racism and Jim Crow. Though considered “one of the most neglected African-American intellectuals” in U.S. history, fortunately today, 50 years after his death, he is beginning to receive the attention he rightfully deserves as a trailblazer in the “long civil rights revolution.”

(Editor’s note: The author is completing a book about Hunton to be published later this year titled The Cancer of Colonialism: W. Alphaeus Hunton, Black Liberation, and the Daily Worker, 1944-1946. The book will include an introduction by Pecinovsky, a short biography of Hunton (parts of which excerpted above), as well as the transcribed collection of all of Hunton’s Daily Worker columns from July 20, 1944, to January 19, 1946. For the first time since their original publication, Hunton’s Daily Worker columns will be made available to general readers.)