Download and print a PDF of this article for easy distribution at May Day events.

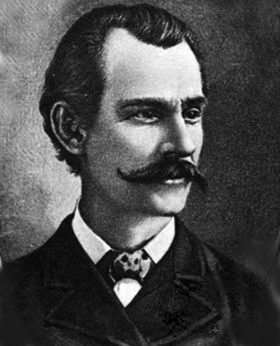

CHICAGO—On the morning of Oct. 6, 1886, Albert Parsons, native of Alabama, whose brother was a general in the Civil War, rose in a Chicago courtroom to make the last speech of his life.

He was facing his doom as one of the convicted so-called “anarchists,” one of the “detested aliens” who had been seized in the police frame-up following an explosion on Chicago’s Haymarket Square during a workers’ demonstration on May 4.

Parsons spoke long and well. He was going back over his life, telling the remarkable story of how the boy who ran with the Texas trappers and Native American traders as a kid grew up to become a leader of industrial strikes and an agitator for a new social system.

“The charge is made that we are ‘foreigners,’ as though it were a crime to be born in some other country,” he said. “My ancestors had a hand in drawing up the Declaration of Independence. My great great grand-uncle lost a hand at the Battle of Bunker Hill.” His speech then took an edge of defiant bitterness. “But I have been here long enough, I think, to have the rights guaranteed by the Constitution of my country.”

Ringing up to the ceiling of the room which was to be his death chamber, the voice of this man, a printer in the shop of the Chicago Tribune and a labor organizer after the early days of the frontier, became deep with exaltation:

“I am also an internationalist. My patriotism covers more than the boundary lines of a single state; the world is my country, and all mankind my countrymen.” Parsons was speaking against a force, a conspiracy that was determined to throttle him, and he knew it. But why was the state determined to see him dead?

The 8-hour day

The demand for an 8-hour workday was sweeping over America at that time as workers demanded relief from the 12-, 14-, or even 16-hour days that were the norm. On May 1, 1886, hundreds of thousands of workers launched a general strike—the first in the history of the United States—which saw demonstrations in all the big cities greater than anything America had ever seen.

But it was in Chicago where the movement reached its height. There, a small core of class-conscious organizers and agitators helped rouse a militant spirit not previously seen. 70,000 workers shut down the plants of that roaring city. At the head of the band of leaders stood the wiry and eloquent Parsons.

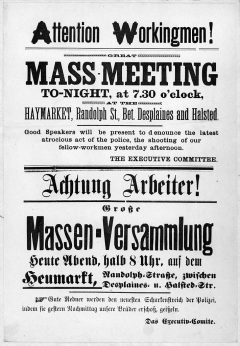

The campaign dragged on for several days. On May 3, there was a bloody attack by the police against strikers at the McCormack Reaper plant. Six workers had been shot in the back, with at least one killed. A mass protest meeting was called to take place the next day at the Haymarket Square.

A peaceful rally took place that evening, with speeches from Parsons and other labor leaders condemning what had happened the night before. A light rain began to fall as the meeting neared its end, and most people began to head home. Without warning, a force of some 200 police officers charged the square. A fight broke out between the cops and the crowd, and then, suddenly, a bomb was thrown. A number of police officers were killed by the explosion. Volleys of police bullets then plowed through the terrified and fleeing audience, killing at least four workers and wounding scores.

No one knew who threw the bomb (and historians have never discovered to this day), but it didn’t matter. The news media of the entire country raged in a red-baiting pogrom which has hardly ever been paralleled. Working-class leaders and trade unions everywhere were targeted. The strategy was to smear the 8-hour movement with the fearful stigma of “alien anarchism” and to kill it. One prominent economist, with characteristic servility, declared the idea that workers should only be on the job for eight hours to be an “irresponsible demand of lunatics aimed at the basis of civilization.” The stage was set for the Haymarket frame-up.

Parsons, along with several fellow organizers, were rounded up and charged with being an “accessory to murder.” Prosecutors eagerly followed advice given by the New York Times to “pick out the leaders and make such an example of them as would scare others into submission.” A Chicago newspaper was even more blunt, with editors writing, “The labor question has reached a point where blood-letting has become necessary.”

The trial was a classic case of intimidation, perjury, and forgery. The prosecution quickly gave up any attempt to prove that the men charged had thrown any bombs. No, the defendants were guilty of a far greater crime. They had inculcated among workers a theory of social change and spread in America the fearful idea of class consciousness.

Socialism on trial

As he faced the gallows, Parsons told the world that it was not just himself and the other defendants who were on trial, but rather the ideas of socialism and workers’ power. He declared to the judge, “Socialism is simple justice, because wealth is a social, not an individual product, and its appropriation by a few members of a society creates a privileged class, a class who monopolizes all the benefits of society by enslaving the producing class.”

Knowing history would absolve the leaders at Haymarket, Parsons spoke his last solemn words to the court: “They lie about us in order to deceive the people, but the people will not be deceived much longer. No, they will not.”

A carefully picked businessmen’s jury sealed their doom and garnered offers of a reward of $100,000 from a grateful “Citizens Committee” of big capitalists. On Nov. 11, 1886, Parsons, August Spies, Adolph Fischer, and George Engel (the latter two weren’t even present at the rally) were hanged at the Cook County Jail, victims of a cold-blooded frame-up. Over 100,000 people followed the bier to their graves at Chicago’s Waldheim Cemetery.

When the Second International, a global organization of socialist and labor parties, was founded three years later in 1889, it declared that May 1st would permanently be known as International Workers Day, in honor of the Haymarket struggle. Thus was born May Day—a global day of struggle and celebration—right here in the U.S.A.

This is an edited version of an article that originally appeared as “Haymarket Hangings Vain Effort to Halt American Labor,” in the Nov. 12, 1937 edition of the Daily Worker.

Read Albert Parson’s final speech as he headed to the gallows in 1886.