“The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of the working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life.”

There’s no doubt that the first line of the Preamble of the Industrial Workers of the World’s Constitution leaves an empowering feeling amongst working people and comrades. It’s a catchy slogan that has been used throughout leftist movements and organizations. The phrase not only serves as a constant reminder of the deep class divide but also serves as a reminder of what our movements are fighting both for and against.

Despite its power, little is known about the person who helped write the Preamble of the IWW Constitution. Most are shocked to find that this person, who was also a founder of the organization, was a Catholic priest, Father Thomas J. Haggerty.

But who was he? What did he do and why has he been mostly forgotten? Can we really consider this lost figure a “saint” of the working class?

The beginning years of his life are very much like his final years, unknown and lost. Little is actually known about his infancy, childhood, and early adulthood. We do know he was born in 1862, but little else until his ordination as a Roman Catholic priest in Chicago in 1895, when he was already in his 30s. It’s unsure when he became radicalized in his political beliefs, though it was probably before he went to seminary. Certainly, by the time he was ordained, his socialist beliefs had taken root—so much so that it worried the Catholic Church and caused his superiors to become involved. This isn’t surprising, given that on May 15, 1891, Pope Leo XIII issued his Rerum Novarum.

In this address, the Pope consistently warns against the “evils” and “injustice” of socialist ideology. He states that “Socialists, therefore, by endeavoring to transfer the possessions of individuals to the community at large, strike at the interests of every wage-earner, since they would deprive him of the liberty of disposing of his wages, and thereby of all hope and possibility of increasing his resources and of bettering his condition in life.” In essence siding with the capitalist, anti-union class, the Catholic Church cynically taught that socialism harms the working class and their ability to thrive—and turned followers of the faith away from the Church. Fr. Haggerty saw quite the opposite of this.

Worried about Fr. Haggerty, the Church decided to put him in the Archdiocese of Dallas, Texas, where they thought he wouldn’t be able to cause any problems. They wanted to put him in places where his socialist rhetoric would affect the least amount of people. Little did the Church know that sending him to Paris, Texas, would only help radicalize him further and make him more active. It was at Our Lady of Victory Church that Fr. Haggerty saw the mistreatment of Mexican railroad workers.

Fr. Haggerty didn’t just do his normal parish work but decided to try to help the workers. He translated French, German, and English socialist material and articles into Spanish for them. His distribution of radical propaganda didn’t go unnoticed. The railroad bosses caught on and sent him a letter warning him to stop. This didn’t frighten the priest, nor did it lead to the kind of holy response that Jesus might have expected from one of his priests. Fr. Haggerty told the messenger, “Tell the people who sent you here that I have a brace of Colts and can hit a dime at twenty paces.” Turning the other cheek was not an option for this fiery Catholic priest.

This event led the Church to move him elsewhere in hopes that he wouldn’t cause any issues. For a time in 1902, he was moved to Arkansas, where his activism only continued to thrive. It was there that Fr. Haggerty preached socialist doctrines to the miners of Sebastian County, trying to convince both Irish union leaders and Catholic immigrants that socialism and Catholicism are able to coexist without contradiction. Besides his work with the immigrants, he also gave a well-attended lecture in Little Rock that focused on the nation’s industrial issues, perhaps setting the stage for his later activism with the IWW. Among his last noteworthy events in the state were his communications and visits with Dan Hogan, the principal leader of the emerging socialist movement in Arkansas. A prominent member of the Socialist Party, Hogan even tried running for office in Arkansas several times. So it was clear that Fr. Haggerty was noticed by party officials and was beginning to create a name for himself.

Once again, the Church took note of the annoyance that Fr. Haggerty was creating. His political activism wouldn’t stop and they needed to move him somewhere else where he couldn’t possibly cause any further problems. In 1903, he was moved to the Archdiocese of Santa Fe where he would be an Associate Pastor of Our Lady of Sorrows Church in Las Vegas, N.M. Incredibly, once again they simply didn’t realize that Fr. Haggerty’s radicalization and activism would increase tenfold at his new place of employment, in part because New Mexico was a hotbed for political activism.

Fr. Haggerty’s political involvement really came to fruition there. Besides his normal priestly duties, he found time to become an editor and primary writer for the Voice of Labor, the official newspaper of the American Labor Union that was short-lived but very active. On top of his journalistic activity, he also began to organize miners all the way up to Southern Colorado to revolt against their management. As expected, this reached the attention of the Catholic Church, leading to Fr. Haggerty’s permanent removal from parish duties. Newspapers and enemies of Fr. Haggerty claimed for years that this removal also included his being defrocked, stripped of his title as a priest. There were no documents to support said claim, however, and he fiercely defended himself. This claim followed him even before his official removal, but time and again he reminded people he was still in communion with the Catholic Church and just as much a member of the Church as the pope. He would remain “Fr.” Haggerty until his last days on earth.

If being removed from the Church weren’t difficult enough, Fr. Haggerty also found himself increasingly frustrated with the Socialist Party. He was a dedicated, active member of the party until he started to see something that troubled him to his core. He started speaking out against the reformist tendencies of what he called the “sidewalk socialists” of the party—he called them “slowcialists”—members who were not so dedicated to the cause as he was. He became so agitated that during one Socialist Party meeting he began to curse and throw insults toward party leaders; the chairman of the meeting even broke his gavel trying to silence him. It took several members to forcibly remove him from the meeting to make him stop. It was at this moment that he knew he was done with the Socialist Party, coming to realize that the working class needed another movement or organization to help steer the struggle forward.

He found this new vehicle via a group of fellow socialists who wanted to form the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). In the fall of 1904, Fr. Haggerty and five of the other original organizers sent out invitations to other leftist organizers to help launch a more radical and militant union.

In the summer of 1905, the group held a conference in Brand’s Hall in Chicago where they officially founded the IWW. Among them were some of the most noteworthy radicals of the time: Lucy Parsons, a radical organizer whose husband Albert was hanged among the Haymarket martyrs; James Connolly, an Irish worker who later returned to Ireland to help organize the Easter Rising of 1916, after which he too would be executed; Mother Jones, whose early Catholic faith had put her on the road to radicalism; “Big Bill” Haywood, who fled to the young Soviet Russia while out on bail in 1921 and took up an advisory role in Lenin’s government; Eugene V. Debs, arguably the most significant socialist in American history.

Many of these individuals admired Fr. Haggerty and his passionate outspokenness. Debs himself described him once, saying, “Tall, massive, erect, he would command attention anywhere. On the rostrum, he is a striking figure, and when aroused is like a wounded lion at bay. He has ready language, logic, wit, sarcasm, and at times they roll like a torrent and thrill the multitude like a bugle call to charge.” He was finally appreciated by his fellow colleagues after his many challenging times with the Church and the Socialist Party. Together, this group of people founded one of the most influential leftist organizations to ever exist in America.

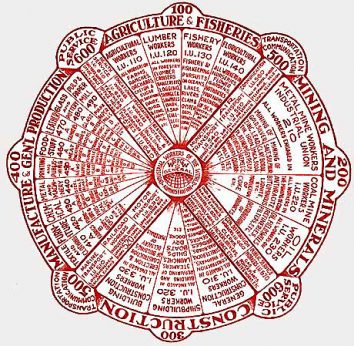

Fr. Haggerty involved himself deeply in the foundation of the IWW. He was the secretary of the Constitution Committee, helping to discuss and write the manifesto that the union would follow. He helped draft the stirring Preamble that is still employed to this day. He was instrumental in establishing the organization and making it a powerful vehicle for working-class struggle. He even created what’s referred to as “Father Thomas J. Haggerty’s Wheel” or “Haggerty’s Wheel of Fortune.” This wheel depicted the trade unions of the working class and their relationship to other trade unions. Though confusing to some, Fr. Haggerty viewed it as giving the organization structure, depicting how the unions represented and correlated within the working class. The wheel was widely used by the organization. One leaflet read, “Study the chart and observe how this organization provides the means for control of shop affairs, provides perfect industrial unionism, and converges the strengths of all organized workers to a common center, from which any weak point can be strengthened and protected.” The wheel is still used by the IWW with some minor edits—several other unions have been added to the organization since the original version.

Despite his dedication to helping the working class, the wheel was one of his last known works before he faded away from the public face of politics and class struggle.

After 1905, Fr. Haggerty dropped out of radical politics, almost never to be heard from again. Little is known about the rest of the radical priest’s life. It was rumored that he gave up his Catholic priest identity and lived the rest of his life somewhere in Chicago. More than a decade later several people did see him. Ralph Chaplin, author of the IWW hymn “Solidarity Forever,” found Fr. Haggerty teaching Spanish and working as an oculist, going not by Thomas Haggerty, but as Ricardo Moreno. John Spargo, a past comrade of the radical priest, who didn’t get along with him in the Socialist Party, found him in 1920 “begging, relying on charity, sleeping at missions, and attending free concerts, libraries, and museums.” Spargo said that Fr. Haggerty didn’t really talk about politics or the movement much, but did seem like he was overall more happy and free—free from the burdens that life had previously weighed on him. After that encounter, no one else reported seeing him again. Nothing is known about his death or where he is buried, most likely in a pauper’s grave. The last half of his life—and his death—are just like the beginning of his life, veiled with mystery.

It’s not hard to explain why many don’t know who Fr. Haggerty was, for there is so little known about his life. Simply put, he was a mysterious person who was only actively political for a very short time. One can only imagine what events, stories, and legends would have survived had he continued his political activism. Though his outburst of renown was fleeting, it’s still fair to say that he was an important figure, perhaps one could say a “saint” of the working class.

Naturally, I don’t mean that he has actually been made a saint by any specific denomination. Rather, I refer to him as a “saint” because he not only fought tenaciously for the working class but successfully applied the religion of the masses to their working conditions and struggles. Fr. Haggerty serves as an activist model for both religious and working-class people.

The official Church despised socialism and its ideals, even though the average worker was suffering and socialism was a clear solution to alleviate it. The Church’s stance didn’t stop people like Fr. Haggerty from trying to be a good pastor and help those in pain and in need. Repeatedly Fr. Haggerty saw the plight of the working stiff and sought to do something about it, show that their faith wasn’t going to stand in the way of this new and better path. He consistently used Catholic imagery in his speeches and pamphlets and showed people that socialism wasn’t the evil that they had been led to believe; that instead their faith and scriptures called for the destruction of capitalism and replacement by a more socialist society. Fr. Haggerty’s militant efforts to guide workers in their faith and their struggle are beyond admirable. All people of faith can look to him as inspiration in their own lives and activism.

If he displayed a quick temper with fellow activists and disdain toward some, if his activist phase lasted but a decade at most, can we really hold this man in such high esteem? Is he really “saint” material for the working class? Even though Fr. Haggerty had flaws, these are what made him human, reminding us that even a “man of God” is imperfect and has his own challenges. This more humanistic approach to Fr. Haggerty only strengthens why we can view him as a saint of the workers because he’s relatable and imperfect like the rest of us. Short-lived as his political activism was, he nevertheless helped to birth a massive change of consciousness in the form of an organization, the IWW (and many other groups that grew out of its legacy) that is still active to this day. He did more with the time he was active than some do their entire lives, and it was quite remarkable.

In the end, Fr. Haggerty was a Catholic priest who did what any person of faith should do: help those in most need. He put his religious beliefs into practice and tried to fight and defend the workers and immigrants as no one else would. Even as the Church placed every obstacle in his way, he still kept going. His activism and work reached the hearts and minds of workers all across the states. He reminded us that religion and socialism are not separate entities, but rather they correlate more perhaps than we want to know. It’s now up to us, those of us who consider ourselves socialists of Christian or any other faith, to take his work and put it to practice.

This forgotten saint of the working class continues to have an impact on all workers, religious and secular alike!

Sources: Preamble of the IWW Constitution; Encyclopedia of Arkansas; Pope Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum: Encyclical Letter of Pope Leo XIII on the Conditions of Labor (1891); Dean Dettloff, “The Radical Ministry of Fr. Thomas Haggerty,” Commonweal, May 17, 2019; “Father Thomas J. Haggerty’s Wheel,” Industrial Workers of the World.