WASHINGTON—Intentional employer “misclassification” of workers as “independent contractors,” stripping them of minimum wages, overtime pay, jobless aid, workers comp, and the right to unionize, is not just a “gig economy” problem, two advocates, and a top enforcement official warn.

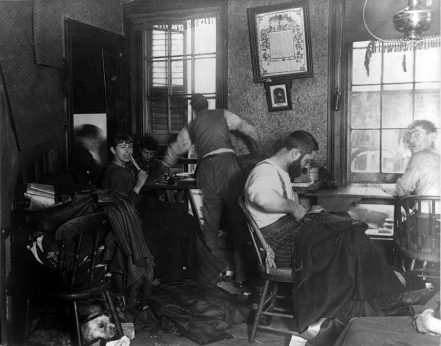

Instead, it’s an increasing tactic of bosses to degrade and exploit workers from coast to coast. One expert warns if companies succeed in their push to turn all “employees,” now covered by labor law, into not-covered “independent contractors,” the U.S. workforce could turn to a “piece work” society, reminiscent of the garment sweatshops of the 1890s.

The panel, the first of two convened by the Economic Policy Institute, discussed both the report, Misclassification, The ABC Test, And ‘Employee’ Status and the expensive and successful campaign by two of the most-prominent “Gig” firms, the rideshare companies Uber and Lyft, to get California voters to permanently let them misclassify all their workers as “independent contractors.”

But the problem goes far beyond Uber and Lyft and far beyond California, EPI reports.

A U.S. Labor Department study reveals “as many as 30% of employers, and perhaps more, have misclassified some workers, affecting millions of workers, disproportionately workers of color,” EPI’s report summarizes. The June 17 EPI discussion was followed a week later by one on international misclassification.

“Workers are misclassified by employers in many occupations and industries, including janitorial services, trucking and transportation, retail, hospitality, home care, and construction,” EPI summarized.

That makes the ride-share firms’ campaign, at a cost of $220 million for one referendum win, important to greedy employers nationally. For Uber, Lyft, and other rideshare firms only, the vote overturned California’s AB5 law. That statute reclassified their drivers—and two-thirds of misclassified workers in the Golden State–as “employees” protected by labor law.

That win will save the two Californian exploiters alone a lot of money: One panelist estimated they’ll garner $100 million a year, just in avoiding employer shares of unemployment insurance, Social Security and Medicare payroll taxes, and workers’ comp money.

It’ll also cost both workers and honest employers, too. The report noted that as soon as voters passed the referendum, Uber and Lyft started cutting their workers’ pay, keeping more of the revenue for the bosses. One Uber driver told a rally in Virginia days later they still are.

And “there are the ones (employers) who are responsible” and pay those costs “and the ones who will break the law no matter what you do, probably forever,” added panelist Lauren Moran, director of the Workers’ Rights Division in the Massachusetts Attorney General’s office.

AB5 established the ABC test to determine if a worker is an independent contractor. If the worker, not the boss controls a worker’s schedule, whether the work is done “outside the employer’s usual course of business,” and whether it’s done by a worker who’s truly independent, then the worker’s a contractor. Otherwise, they’re protected under labor law, as “employees.” Under those standards, Uber, Lyft, and other similar drivers were “employees.”

AB5, which stays in effect for other gig workers, so far, said the worker’s job and independence must satisfy all three of those conditions for the worker to be an “independent contractor.” And California had ruled the one million rideshare drivers, most of them toiling for Uber and Lyft, weren’t.

Others still protected

The win in the referendum left AB5 in place protecting other vulnerable workers. They include construction workers, port truckers the Teamsters are trying to organize on the West and East Coasts, home health care workers, adjunct professors, even fast-food workers.

“One-quarter of our janitors are misclassified as independent contractors,” added Ken Jacobs, director of the Labor Center at the University of California at Berkeley.

And flushed with their success in the nation’s most populous state, the two rideshare firms want to take their “independent contractor” drive coast to coast, as other bosses look on and ponder how they, too, can join in the exploitation.

“We’ve been fighting misclassification for 25 years,” said Caitlin Vega, a longtime Teamsters organizer and lobbyist and a director of the union campaign against Prop 22, the Uber-Lyft referendum to make all their workers “independent contractors.”

AB5, she added, “is an everybody bill,” because it protects current workers from being arbitrarily converted into contractors. “It’s really them”—Uber and Lyft—“who are arguing for a different standard,” and a lower one, for their workers.

The workers and their allies lost because they were outspent and because Uber and Lyft recruited compliant drivers to talk about how being independent contractors gave them “flexibility” to drive when they wanted, and to turn down fares they didn’t want. Left unsaid: Many of the unwanted fares were riders of color or to communities of color.

But the workers also lost, Vega admitted, because supporters of AB5 “couldn’t show immediate results” for workers from the law.

There is, however, one ray of hope on the horizon to bring the Uber-Lyft independent contractor dodge to a screeching halt, says Bart Sheard, a worker in the AFL-CIO Legislative Department: The Protect the Right to Organize (PRO) Act.

Among other labor law reforms, the PROAct would write the ABC test into federal law, making it extremely difficult for bosses to impose the “independent contractor” label and exploitation on workers.

“Since the House passed the PROAct, power on the ground” for it “has really grown,” Sheard said. “And it’s not just labor. Civil rights groups, human rights groups” and other groups “all conclude it’s important to shift this country away from the race to the bottom.

“Employer groups, the Chamber of Commerce, Uber and Lyft are all creating ‘The sky is falling!’ fear-mongering,” if Congress sends the PROAct to Democratic President Joe Biden, who has campaigned hard for it and promised to sign it. “There’s a lot of talk about going out of business” if that occurs.

“Well, a number of states already have the ABC test,” including Massachusetts, “and they haven’t seen masses of ‘going out of business,’” signs.

Video of the discussion is on EPI’s YouTube channel.