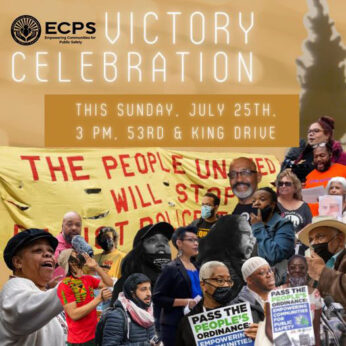

CHICAGO — Chicago’s City Council approved a community oversight system this week giving representatives chosen by the community a solid measure of control over Chicago police following years of protests and mobilizations over law enforcement misconduct.

The 36-13 vote capped more than two years of struggle by a broad coalition of groups including unions, community organizations, civil rights groups, and others. That struggle, many of the groups involved say, is what brought Mayor Lori Lightfoot around to backing a compromise that could be supported by the community activists.

The demonstrations and actions demanding community control of the police, although having gone on for years, increased here after the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis and the continuation of fatal police shootings by Chicago cops.

The ordinance establishes a citizen panel to oversee Chicago police — but not with all the powers originally demanded by many of the community activists. The oversight board will be able to vote for removal of the police superintendent but will not have the final authority to do so. The city agreed to give the board the power to vote for removal after the community groups agreed to drop their demand that they be able to directly fire the superintendent.

The real victory here is for the forces in Chicago and elsewhere that believe safety and security in the city streets is best achieved when there is community control of the police.

“It’s the real way to guarantee a safe and secure city,” said Frank Chapman, chair of the Chicago Alliance Against Racist and Political repression.

“Unless you have community control you really have nothing, regardless of how much money you allocate or take away from police. The real issue is that community control is the way to achieve safe and secure neighborhoods. People in the communities know their needs the best.”

Chapman attributed the positive development in Chicago to “the broad coalition we had fighting for this for years. We had nine unions, countless community groups and religious groups representing Muslims, Jews and Christians, the Coalition of Black Trade unionists and so many more,” he said.

Chapman’s organization and the Grass Roots Alliance for Police Accountability were the two main groups, Chapman said, leading the successful coalition.

“This ordinance is predicated on the belief that when you empower our communities, that when you give them a real seat at the table and you give them a real voice, that we can make our policing system better and we can have a safer city in every single neighborhood, on every single street,” said Carlos Ramirez-Rosa, a member of the City Council who helped negotiate the compromise deal.

North Side Alderman Harry Osterman, a co-sponsor of the oversight plan, said it can help establish trust between Chicagoans and police because residents will have a hand in crafting policy.

“We, as a city, cannot have safety, true safety, in every neighborhood unless there is trust between citizens and police,” Osterman said.

Elections will be held to name members to 22 district councils across the city. A seven-member Community Commission for Public Safety and Accountability would be chosen by them in consultation with the mayor.

Initially, Mayor Lightfoot gets to select the members of an interim commission, a president and six other members, from among 14 nominees chosen by the City Council Rules Committee.

In 2023, elections would be held in each of the city’s 22 police districts, to name three-member councils in each district.

Each district council would name a member to serve on a nominating committee, which would submit the names of nominees to the mayor to fill the seven-member Community Commission.

The mayor would be free to accept the nominees or reject them. The nominating committee would then keep submitting nominees until the mayor accepted enough people to serve on the commission.

Once in place, the commission would be able to vote to remove the chief administrator of the Civilian Office of Police Accountability that investigates police shootings and reports of wrongdoing. If two-thirds of aldermen agreed, the chief administrator would be removed.

The commission would also be able to vote to remove the police superintendent, but the mayor could accept or reject that recommendation.

The commission could adopt new Police Department policies, but the mayor could veto those rules. A two-thirds vote of the 50-member City Council would be needed to override the mayoral policy veto.

The ordinance itself needed a two-thirds majority, or 34 votes, to pass the 50-member council Wednesday rather than a simple majority because it sets regular citywide elections to let voters pick members of district police oversight councils.