In a field near Arvin, at the southern end of California’s San Joaquin Valley, dozens of workers arrive at 5:30 in the morning. It’s already over 80 degrees, and by midafternoon the temperature will top 114 degrees, according to my iPhone.

Is this heat normal? The southern San Joaquin is a desertlike pan between the high Sierras and the Pacific Coast ranges, whose rivers have been diverted into giant irrigation projects. High temperatures are the norm. In 1933 the thermometer reached 116 degrees on July 27. The high this past July was 112.

In the summer, cars line the valley’s rural roads and highways, next to field after field. Even before daybreak, people stream from their vehicles into the rows and vines. By starting early, farmworkers can get seven or eight hours in before the heat reaches its peak. Most head home then, but some continue on, despite the temperature.

Farmworkers in the San Joaquin Valley have no choice but to treat the heat in a matter-of-fact way – laboring through the summer means survival in the rest of the year. Summer is the season with the most demand for field labor, so people get in whatever hours they can, hopefully saving enough money to weather the months when work is scarce.

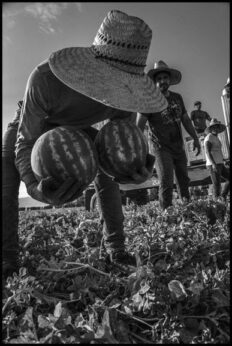

It’s easy to pick up a bag of delicate small bell peppers in the supermarket, or lift a heavy watermelon out of the bin, without thinking about what it must have been like to get them from field to city in this summer’s heat. But in California, workers used to die from it.

In 2005, after four workers died from heat exposure, California began requiring growers to provide adequate water, shade, and rest breaks. But in 2008, 17-year-old Maria Isabel Vasquez Jimenez died from working in the grape harvest in 95-degree heat. That led to stricter standards and more enforcement. Nevertheless, at least 14 California farmworkers died of heat-related illness between 2005 and 2015.

A recent report by Vermont Law School’s Center for Agriculture and Food Systems, “Essentially Unprotected,” points out that only California, Minnesota, Washington, and, most recently, Oregon have any requirements mandating heat protection for farmworkers. There is no federal heat standard, although unions have fought for one.

An article this year in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine warned, “Immigrant farmworkers will often suffer through [heat-related illness] rather than report it as they do not want to be fired for being perceived as a bad worker, lose income, or let down coworkers, especially if they are being paid by piece rate rather than by time.”

Yet, despite the heat, the immigrant workers in these photographs were out in the fields, laboring to provide the food for Los Angeles, San Francisco, and the rest of this country’s cities, with their sweat earning the money their own families need to live.