When AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka passed away recently, it brought back memories of our first encounter in Connecticut in 1989. He was the young president of the United Mine Workers of America at the time, and he called me looking for help with his strike against the Pittston Company. He was planning to bring a group of strikers from Virginia to the coal mining company’s corporate headquarters in Greenwich to have a loud presence at its shareholders meeting.

He didn’t know anyone in Connecticut, and I had never worked with the Mine Workers Union before. I was the president of the Connecticut State AFL-CIO, so he reached out to me. He wanted community support. The miners were not part of our organization, but that didn’t matter. Their backs were against the wall, and we were determined to help them.

People think of Greenwich as a glitzy Gold Coast bedroom community for CEOs and wealthy coupon clippers. But I grew up there. I knew the fabric of this community was woven with more than one thread. I knew community leaders and the police, and I was close with the governor.

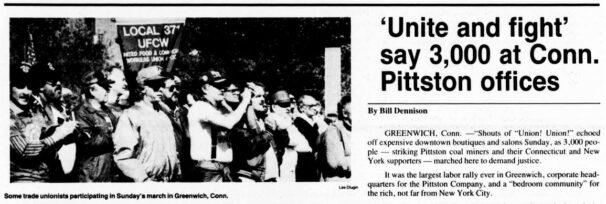

Some 80 mine workers traveled 16 hours by bus from the coalfields of Virginia and stayed in Greenwich for six months. The first rally was small, but they kept getting bigger and bigger, leading up to the shareholders meeting. This was a time of renewed militancy in the labor movement after two terms of the Reagan administration. On the day of the largest rally, Sept. 24, 1989, there were 1,500 people in the streets of Greenwich. We were joined by striking machinists and flight attendants from Eastern Airlines and members of the Communication Workers of America who had been on strike at the telephone corporation NYNEX.

Trumka trusted my instincts about handling the police. He was used to conflict in the coalfields, but this was different. I went to the traffic division leaders of the local police and told them we didn’t want this to get out of hand. We didn’t need a show of force. I knew there were machinists looking for a confrontation. I also knew we had the state police out of sight at the Knights of Columbus in case we needed them. We marched through town to an outdoor amphitheater that Greenwich gave us facing Long Island Sound. It was an impressive sight.

What stuck with me was the way Trumka inspired his members. Pittston had taken away their health care, expanded their workweek to seven days, and refused to negotiate a new agreement. The company had also cut off health coverage for retired mine workers. He spoke eloquently about the health care crisis in our country—38 million without any health care at all. A Greenwich clothing store owner I knew had thought the strikers were going to be disruptive. Hearing about their situation changed her mind.

But the eyes of those coal miners—that’s what I’ll never forget. They believed in Rich Trumka. He told them that this was about survival, about holding their union together, about everything they had fought for: health care, black lung benefits, a day off. He said they would hold off one day longer than Pittston, and that’s what they did.

Everyone said it was a strike Trumka couldn’t win. For the strikers, losing was not an option. It was a life-or-death situation for the union.

Today, we have a U.S. president who talks about unions and jobs and dignity. That’s what Rich Trumka did for us before he passed away. He brought the American labor movement together for an all-out effort in the 2020 election. He did the same thing he told his own members in 1989: You can’t win if you don’t fight for it.

From the People’s World archives:

> Sept. 1989: Trumka says labor is on verge of new era

> Nov. 2013: Olsen retirement – “Solidarity forever” is union leader’s legacy

Originally published in New Haven Register Aug 17, 2021