The Toronto International Film Festival is naturally the place to go to see great Canadian films, and there was no shortage this year. Of course, we all know about the highly anticipated remake of Frank Herbert’s sci-fi epic, Dune, by Canadian director Denis Villeneuve (Incendies, Arrival), which premiered at TIFF this year.

The Toronto International Film Festival is naturally the place to go to see great Canadian films, and there was no shortage this year. Of course, we all know about the highly anticipated remake of Frank Herbert’s sci-fi epic, Dune, by Canadian director Denis Villeneuve (Incendies, Arrival), which premiered at TIFF this year.

A main theme in Canadian films is the history of the First Nations and their relations to colonial exploiters. “A treaty made is a treaty broken” applies most every time Native people are involved. The sordid history of British colonialism in Canada encompasses the tragic “kidnapping” of Native children from their tribes, to be “civilized, moralized and made into respected Christians.” Recent shocking news tells of the discovery of unmarked mass graves found near schools where First Nation children were forced to attend. The country seems determined to right these wrongs and has made major advancements in telling the true and mostly unknown history of the Indigenous people. Most importantly, Natives have become powerful voices in the Canadian world of cinema and much is to be learned from them.

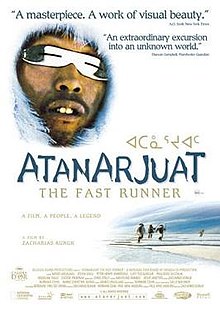

The most celebrated Canadian First Nation filmmaker was honored with a Special Program, Celebrating Alanis Obomsawin, screening most of her vast cinematic contributions. This included a 20th anniversary 2K restoration of her 2001 award-winning documentary, Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner, a masterpiece of visual beauty and a landmark in Canadian cinema. It was the first Inuit film written, directed, acted, and spoken in their native language. It’s an epic based on an Inuit folk tale about love, revenge, betrayal, and murder in the far north regions of Canada.

The most celebrated Canadian First Nation filmmaker was honored with a Special Program, Celebrating Alanis Obomsawin, screening most of her vast cinematic contributions. This included a 20th anniversary 2K restoration of her 2001 award-winning documentary, Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner, a masterpiece of visual beauty and a landmark in Canadian cinema. It was the first Inuit film written, directed, acted, and spoken in their native language. It’s an epic based on an Inuit folk tale about love, revenge, betrayal, and murder in the far north regions of Canada.

The Native struggle continues in Night Raiders, the first feature film from director Danis Goulet, a Cree-Métis from northern Saskatchewan. An allegory about First Nation children, the action thriller is framed in the sci-fi genre about a future dystopian society where the rich are walled off from the “beggars and freeloaders.” Sometime in the near future, after living in the “bush” for six years, a Cree mother and her daughter fight for survival against the drone-armed modern automatons that keep earthlings in their bullseye, and capture children for their forced education. They enter the state zone and the mother is forced to leave her child to be kidnapped by the state that enslaves, brainwashed, and creates robots for the defense of the “free and democratic” state. They are taught to hate their own family and culture.

A virus is created by the government as an excuse to start another war. A Native ruminates about colonialism, saying, “as long as we have one piece of land, they will always come for us.” The state school’s leader, who looks uncannily like Nancy Pelosi, stares over the students as they are forced to recite and live by every word: “We pledge our hearts and give our allegiance to our glorious Republic. We praise the great Southern Nation for emancipating us and solemnly swear to protect it in the name of God, our liberty, and freedom. One country. One language. One flag.” Not surprisingly, the film’s executive producer is the New Zealand film wonder Taika Waititi, (Jojo Rabbit), whom some people call “the Michael Moore of people of color films,” meaning he puts his earnings toward promoting other progressive artists and projects. (Check out his Reservation Dogs series on Hulu.)

Working-class Montreal-born pianist extraordinaire Oscar Peterson is honored in a beautiful documentary treatment of his life as one of the world’s greatest jazz musicians. Oscar Peterson: Black + White covers his extensive touring career in music, and adds personal insight with interviews from the likes of Herbie Hancock, Branford Marsalis, and others. Peterson’s tours often brought him face to face with racism in its various forms, and even though his life was mostly music-driven, he did have an interest in social justice, one expression being a moving political piece, Hymn to Freedom, which was dedicated to Martin Luther King, Jr. and was performed at Barack Obama’s inauguration.

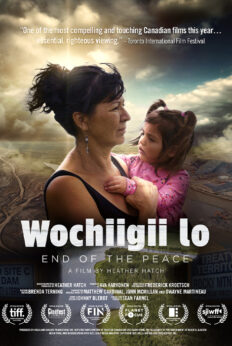

Wochiigii lo: End of the Peace is a searing and emotional documentary about the destruction of Indigenous land in Canada. The Site C Dam in British Columbia is a hydroelectric project that cuts through the Peace River, and First Nation inhabitants are fighting to protect their land and culture. The doc is filled with the expected indignation of the victims and the seemingly clueless insensitive responses from the perpetrators. This film keeps you glued to the battle in a powerful opportunity to learn the history of the first people in the region.

Wochiigii lo: End of the Peace is a searing and emotional documentary about the destruction of Indigenous land in Canada. The Site C Dam in British Columbia is a hydroelectric project that cuts through the Peace River, and First Nation inhabitants are fighting to protect their land and culture. The doc is filled with the expected indignation of the victims and the seemingly clueless insensitive responses from the perpetrators. This film keeps you glued to the battle in a powerful opportunity to learn the history of the first people in the region.

A couple of Canadian shorts also stood out for progressive viewers. Defund follows Toronto twins who each find their own way of dealing with the pandemic and civil unrest in the hot summer of 2020. Terril Calder’s Meneath: The Hidden Island of Ethics proves the power of stop animation to deliver a powerful social message about a young Métis girl who has to make choices, besieged as she is by the incessant attempts at indoctrination from various sources.