LOS ANGELES — An enlisted man strikes out at his commanding officer during wartime and is promptly sent to the brig. The charge is mutiny. This may sound like the germ of Herman Melville’s novella Billy Budd, memorably turned into an all-male opera by Benjamin Britten, with a libretto by the English novelist E. M. Forster and Eric Crozier. Indeed, that is one acknowledged source of A Solder’s Play, now in an impressive, high-testosterone staging at the Ahmanson Theatre here.

The other source for the play was the personal experience of playwright Charles Fuller (1939-2022), who witnessed not only overt racism coming from the white military establishment but also the deep-seated self-loathing and internalized racism among his fellow troops. Fuller identified the kind of self-hatred of an educated, upwardly aspiring Black army sergeant in a segregated unit during World War II that would lead to verbal and physical abuse of other men he considered both his inferiors and poor role models for their race.

Now answer me this: How is it that Fuller’s play, first staged Off-Broadway by the Negro Ensemble Company, in a run that lasted 468 performances from Nov. 20, 1981, to Jan. 2, 1983, with a cast that included Adolph Caesar, Denzel Washington, Larry Riley, Samuel L. Jackson, Peter Friedman, and Charles Brown, that won the playwright a Pulitzer Prize for Drama, that toured the U.S. from 1984 to 1985 and was adapted (by the playwright) into a 1984 film, never made it to Broadway’s, uh, Great White Way until 2020?

Fuller himself, in interviews about his work, said his play was simply too radical to interest a Broadway producer. Specifically, he would not cut the play’s last line: “You’ll have to get used to black people being in charge.”

Finally, in January 2020, Roundabout Theatre Company presented A Soldier’s Play in its Broadway debut, starring David Alan Grier and Blair Underwood, directed by Kenny Leon. It won the 2020 Tony Award for Best Revival of a Play. It had given 55 performances as of March 8, 2020, when the Covid curtain dropped. Post-pandemic, Roundabout is sponsoring a national tour for the 2022-2023 season starring Norm Lewis as the investigating Captain Richard Davenport, and Eugene Lee, who had appeared in the original 1981 production as Corporal Bernard Cobb, as the central figure of Sergeant Vernon C. Waters, the abusive officer who is shot to death in the opening scene, just as he realizes that despite his naïve post-racial aspirations, “They still hate you!”

Finally, in January 2020, Roundabout Theatre Company presented A Soldier’s Play in its Broadway debut, starring David Alan Grier and Blair Underwood, directed by Kenny Leon. It won the 2020 Tony Award for Best Revival of a Play. It had given 55 performances as of March 8, 2020, when the Covid curtain dropped. Post-pandemic, Roundabout is sponsoring a national tour for the 2022-2023 season starring Norm Lewis as the investigating Captain Richard Davenport, and Eugene Lee, who had appeared in the original 1981 production as Corporal Bernard Cobb, as the central figure of Sergeant Vernon C. Waters, the abusive officer who is shot to death in the opening scene, just as he realizes that despite his naïve post-racial aspirations, “They still hate you!”

Whether or not you are already familiar with this work, what we see on stage here is theatrical history and history-making. Run, run, run!

The play is structured as a murder mystery. Who shot Sgt. Waters? Local Ku Klux Klansmen in the woods surrounding Fort Neal, Louisiana? White officers resentful of African Americans rising to anything above cooks and janitors in the army? The brass have sent in a Black lawyer, a graduate of Howard University Law School, one Capt. Davenport, to investigate. He arrives and is promptly advised that no one on the base or in the local community will take him seriously and that his investigation is all but dead on arrival. This is a case best buried and forgotten as quickly as possible, his services are not needed. “Our war,” he is told, “is with the Nazis and Japs, not the civilians.” Davenport, of course, has different ideas and is prepared to make sure the Black press is apprised of this murder of a Black officer (and the subsequent cover-up).

Over the course of two riveting acts, we experience not only the white officers’ mystification at being forced to accept a fellow Black officer as an equal but also the Black troops themselves in a wide range of backgrounds and personalities. The character of Private C.J. Memphis (Sheldon Brown) is central—as the “Billy Budd” figure—an innocent with musical talent who is beloved by all except Sgt. Waters, who sees in him only a backwoods jiving Uncle Tom simpleton who brings discredit to the Negro race. Curiously, of all the men under Waters who chafe at his abusive ways, it is C.J. alone who has the deeper intuition of Waters as a man of terribly conflicted self-image.

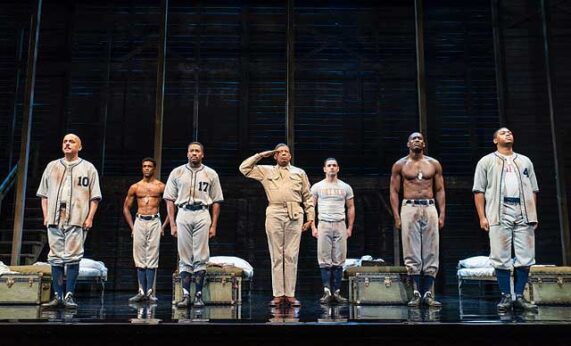

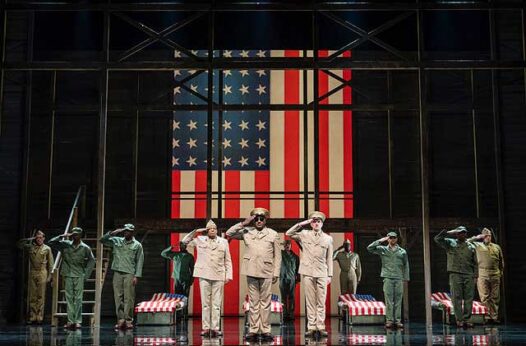

The staging is rich with African-American patois, vigorous, uninhibited physicality and gesture, Delta blues, rhythmic choral song deriving from work crews and/or prison gangs, and Black fraternity step dance that introduces sly choreographic blue notes to satirize strict military march discipline. The entire production (set design by Derek McLane, costumes by Dede Ayite, lighting by Allen Lee Hughes, sound by Dan Moses Schreier) is a joyous barracks spectacle that gives full honors to a modern classic of the American stage.

It’s our national shame to admit it, but the issues raised here about race relations in 1944 are still very much with us.

“The recent passing of The Giant that is Charles Fuller has only magnified his brilliance…an amazing writer who left us so much with his masterful A Soldier’s Play,” says director Kenny Leon. “We honor him with this American tour of the Broadway production…. Come—laugh, think, and reflect—America is in need of love.”

By the end, after months of waiting, training, and many baseball games (these guys beat the white team every time), the 1944 call for mobilization is sounded. “Ike needed to see if the colored boys could fight,” someone quips. Though the theme of the Double V for Victory is not referred to (not that I heard, anyway) —V for victory against America’s enemies abroad, and V for victory against racial discrimination at home—these men are ready to join the fray and beat the Nazis and the Japanese. They are eager to prove themselves through service and sacrifice without loss of their identity as African Americans.

By the end, after months of waiting, training, and many baseball games (these guys beat the white team every time), the 1944 call for mobilization is sounded. “Ike needed to see if the colored boys could fight,” someone quips. Though the theme of the Double V for Victory is not referred to (not that I heard, anyway) —V for victory against America’s enemies abroad, and V for victory against racial discrimination at home—these men are ready to join the fray and beat the Nazis and the Japanese. They are eager to prove themselves through service and sacrifice without loss of their identity as African Americans.

Aside from roles and actors already mentioned, the cast includes Will Adams as Cpl. Bernard Cobb, Malik Esoj Childs as Pvt. Tony Smalls, William Connell as Capt. Charles Taylor, Alex Michael Givens as Cpl. Ellis, Matthew Goodrich as Capt. Wilcox, Chattan Mayes Johnson as Lieut. Byrd, Branden Davon Lindsay as Pvt. Louis Henson, Tarik Lowe as PFC Melvin Peterson, Howard W. Overshown as Pvt. James Wilkie. In these days of uncertain health, the importance of understudies in the theatre has been greatly heightened. In this production, they are Alex Ross, Brandon Alvión, Ja’Quán Cole, Charles Everett, and Al’Jaleel McGhee, whom you may see at any given performance.

Tickets for A Soldier’s Play are available through CenterTheatreGroup.org, Audience Services at (213) 972-4400, or in person at the Center Theatre Group Box Offices (at the Ahmanson Theatre) at The Music Center, 135 N. Grand Ave., L.A. 90012. Performances run Tues. through Fri. at 8 p.m., Sat. at 2 and 8 p.m., and Sun. at 1 and 6:30 p.m. Join the cast immediately following the performance for special talkbacks on June 7 and June 14. Norm Lewis shares his thoughts on his role in A Soldier’s Play, his career, and the importance of live theatre.