Art is labor. It’s really that simple. Creative professionals have crafted their art into a career. While there’s no dispute that the work of musicians, writers, actors, and dancers, as well as visual, film, and performance artists, begins with visceral inspiration, our pride lies also in our success. Art is labor. It’s highly specialized, it requires countless hours, boundless energy, and visionary determination.

If art is work, why aren’t musicians and other artists viewed as workers?

Much of the problem lies in the oddly American concept that creative pursuits are but hobbies, perhaps side gigs at best. But another reason for this misconception can actually be found within artists: When we separate ourselves from other workers—and other unions—we can easily fall prey to the divisiveness that’s long been weaponized against the labor movement for well over a century.

The most radical years

Artists—cultural workers—of an earlier age came to understand the need for unity among all workers in the fight for fair wages, job security, and other factors of workplace justice. We can look to the radical years of the 1920s and particularly the ’30s as the performing and fine arts unions as well as “fraternal” and professional organizations of creatives grew in breadth, reach, and diversity, often carrying with them a stinging militant intensity.

The scope soon widened to encompass free speech, health and safety laws, racial justice, and women’s and immigrants’ equality, as well as the battle against child labor. Ultimately, labor’s agenda came to include sick leave, the 40-hour work week, vacation, holidays, benefits, pensions, the grievance and arbitration process, and of course the contracts negotiated to legally ensure all of this.

The Associated Musicians of Greater New York, American Federation of Musicians (AMF) Local 802, was founded in an act of rebellion at that time. It recognized the immediate need for a union built on racial equality and inclusion, as did the reconstructed Screenwriters Guild (now WGA), Screen Actors Guild, and Actors Equity, followed by the Guilds of Variety Artists and Musical Artists, among others.

Highly relevant to artists’ liberation were the left-wing organizations such as the national John Reed Club, a radical multi-arts grouping named for writer and journalist Reed, and its associated collectives. Among these were the Artists Union, the Workers Music League, and the esteemed Composers Collective of New York, which included Aaron Copland, Elie Siegmeister, Charles Lewis Seeger, Henry Cowell, Ruth Crawford, and Marc Blitzstein.

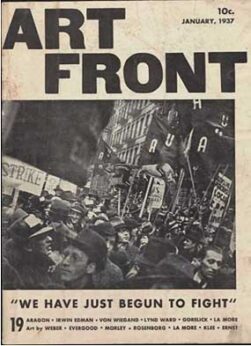

Other such vital organizations were the Harlem Artists Guild, the League of American Writers, and the League of American Artists. These formal organizations had constitutions, held regular strategizing meetings, and staged important events. Most had their own journals as well, such as Art Front.

The boldness of cultural workers during those years is best exemplified by this quote from Charles Lewis Seeger, musicologist, founder of the Composers Collective, and the father of Pete Seeger, who, years later would be renowned for his own music of social change:

“We felt urgency in those days…. The social system is going to hell here. Music might be able to do something about it. Let’s see if we can try. We must try.” (“Unsung Songs of Protest: The Composers Collective of New York,” New York Folklore)

Today’s labor movement and the arts

The recent period has exemplified a new day of labor unrest in almost every quarter, and strikes across the country have empowered the movement.

Among arts workers, this year we’ve witnessed a powerful campaign by the Writers Guild of America, sustaining a 148-day strike which ended in a historic victory. And SAG-AFTRA entered its negotiations brandishing a strike vote against the same AMPTP. SAG-AFTRA’s strike also resulted in another stunning win, following strong and tireless support from the arts unions as well as the wider movement.

Among arts workers, this year we’ve witnessed a powerful campaign by the Writers Guild of America, sustaining a 148-day strike which ended in a historic victory. And SAG-AFTRA entered its negotiations brandishing a strike vote against the same AMPTP. SAG-AFTRA’s strike also resulted in another stunning win, following strong and tireless support from the arts unions as well as the wider movement.

The AFM, Actors Equity, IATSE, AGMA, AGVA, and others within and beyond the entertainment and arts community, have stood by these union siblings all along.

Some of these trends began even earlier, as evidenced by the Local 802 members who are faculty at the New School’s School of Jazz and Contemporary Music. In militant support of our ACT-UAW co-workers, 802 refused to cross the picket line and engaged in multiple demonstrations of solidarity, marching, and playing music, in the streets of Greenwich Village.

Following ACT-UAW’s smashing success, our members saw the benefit of such mutual activism when our own negotiations committee demanded and won a contract of parity for the first time. And more recently, there was an outpouring of support for the actions of the New York City Ballet Orchestra. When faced with a seemingly insurmountable struggle, there’s nothing to compare with the sight of union comrades standing, marching, and chanting during multiple rallies.

In the current climate, with reactionary anti-union sentiment from the political right-wing, the business sector, and whole segments of governance, solidarity must become both mantra and mission.

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and journalist, and songwriter Ralph Chaplin in particular, coined the oft-heard phrase “Solidarity Forever” in his 1911 song of the same name. The IWW reinforced this with the lasting slogan “An injury to one is an injury to all,” the heart of solidarity itself.

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and journalist, and songwriter Ralph Chaplin in particular, coined the oft-heard phrase “Solidarity Forever” in his 1911 song of the same name. The IWW reinforced this with the lasting slogan “An injury to one is an injury to all,” the heart of solidarity itself.

This article originally appeared in the December 2023 issue of Allegro, the journal of AFM Local 802.

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today. Thank you!