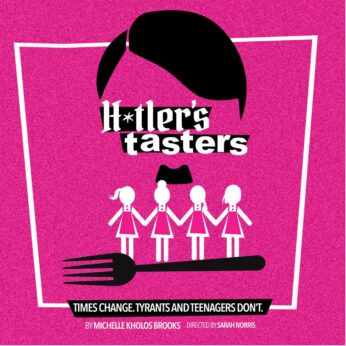

LOS ANGELES – Written by Los Angeles playwright Michelle Kholos Brooks, the uninterrupted genre-defying 85-minute play H*tler’s Tasters opened April 27, and I was eager to see it. Brooks reimagines the historical protocol at Hitler’s Wolf’s Lair in a production directed by Sarah Norris on the tiny (ca. 40-seat) immersive Henry Murray Stage upstairs at the Matrix Theatre.

An earlier production of the play had been set for a run in L.A. but managed to realize only two performances in March of 2020 before COVID forced it to shut down.

An earlier production of the play had been set for a run in L.A. but managed to realize only two performances in March of 2020 before COVID forced it to shut down.

Brooks conceives H*tler’s Tasters as a “dark comedy,” about the largely unknown story of young German women conscripted to taste Adolf Hitler’s food for poison—as rulers in many other times and places similarly had their gastronomical watchdogs. Over the course of World War II, with rampant rumors and suggestions of plots against the Führer, some 15 young women had been recruited for this singular “honor” at Hitler’s Wolf’s Lair, and only one of them survived. They count it as a mark of their chosen status that they dine off bone china plates with sterling silver utensils and gold cups.

The L.A. production is not its first. Centenary Stage, in Hackettstown in northwest New Jersey, gave the play its world premiere. The work won the Susan Glaspell Award, and was named Best of Fringe at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival by The Stage (UK). It is produced in its current outing by Guillermo Cienfuegos and Lexi Sloan.

The premise of the play, as well as its promise, had me.

Knowing that readers are mostly not in Los Angeles, I often like to include some background, history, and artistic notes from the creative team to enlighten those who will likely never be able to see a given play. I’m going to be especially generous today quoting the playwright (from her program notes), because who better than her to explain how she got interested in the topic, how the subject resonated with her, why all the modernisms in a World War II-era drama, and what implications this story holds for us today?

“A few years ago, I thought I had heard every crazy, twisted story possible about Adolf Hitler. Then, at 94 years old, a woman named Margot Wölk told her extraordinary tale of being conscripted to be one of his food tasters. I could not get my brain around the idea that Hitler very specifically chose young, German women, the future of the Reich, to test his food for poison. Everything that pushes my buttons of concern is encapsulated in this story; the way society treats young women as expendable; the way children are used as tools of war; the complicated relationships young women have with themselves and each other—not to mention the complicated relationship that women have with food! And the idea of young women stuck in a room together waiting to see if they were going to live or die after every meal?

“Could there be a riper situation for drama and (dark) comedy? Isn’t adolescence hard enough? Times change, people don’t.

“One day, as I was thinking about this story, I watched a group of young women take photos of themselves in pursuit of the perfect selfie, and I realized that those women—those girls, really—were likely the same age that the Tasters would have been. Their dreams and desires would be the same. I determined that I wanted the girls of H*tler’s Tasters to feel very present and very alive. I did not want them to be sepia-toned people in history. That is why H*tler’s Tasters is woven with anachronisms and contemporary references. Some of these references happened quite by mistake. For instance, when I wrote the play, I didn’t know that children would be separated from their parents at the border—I only knew that this had happened during the Holocaust. When I first conceived of this story, I couldn’t have imagined that all of us would be stuck in rooms, waiting for our fate to be revealed—unsure of who we could trust to keep us safe. For a long time in 2020 we didn’t even know if our food was safe!

“H*tler’s Tasters feels more relevant today than when I conceived of it a few years ago. I wish it wasn’t. I wish I had written a story that was trapped in amber—isolated in history. But the young women of H*tler’s Tasters are powerful reminders of what can happen when a society indulges in complacency and fails to notice that what affects some of us, eventually affects all of us. The girls in H*tler’s Tasters are the girls who didn’t fight. Their families didn’t catch the signs, or, worse, they looked the other way. Their neighbors accepted the ‘inevitable.’ What they failed to realize is that madmen first come for the ‘other,’ but when there are no ‘others’ left, they turn on their own.”

A “minority of one?”

I may lag behind as a “minority of one” in my critical assessment, but to my eyes and ears, Brooks has pretty much just said everything she means to. The rest—the play itself—is mere exposition. The 85 minutes go by with much expressionistic repetition—meal after meal, selfie after selfie, sexual fantasy (with Frank Sinatra or Adolf Hitler, take your pick) one after another.

The acting and production are very fine, however, which in the moment impress. How much theater takes place in a space barely larger than a kitchen! In between meals, director Norris has her cast dance into a change of clothes, meaning another day, another dietary adventure in suspended animation. The action is sometimes loose and free, in movement as with words and verbal assaults on one another (they yell “bitch” at each other probably a dozen times in the script), as the girls let themselves be teenagers—the only expression of agency they will show. And when it comes to mealtime, it all becomes mechanical, ritualistic, determined, like something out of Elmer Rice’s 1923 play The Adding Machine: All lift their forks with the same angular motion and clear their plates at the same time, waiting an hour to see what happens.

The girls’ interaction with the outside (they do go home each night) is more hinted at than shown: Bones lying about in a field where a lovely, only slightly damaged red overcoat is recovered, Hilda’s career officer father who has not been heard from in months, flirtations (maybe more) with handsome soldiers, Anna not sure if the Russians are on the German side or not, one girl’s childhood friendship with a Jewish banker’s family that one day simply disappeared, watching as other neighbors are spirited away, German families reduced to scavenging for caloric intake they would never have considered eating before, spotty news from the front.

Brooks studs her script with contemporary quips as if to boldly underscore how little things have changed: Black singers matter! The Reich tells us what we need to know—anything else could be fake. This job sucks! Where’s the beef? (The Führer is vegetarian, so meat never appears on their plates.) It will all be so much better once he makes everything great again. Jews cannot replace us! The Führer wouldn’t force himself on us—I’m not Poland! He’ll arrive on a beautiful white horse with his shirt off. We’re the chosen people! Thank you for your service!

As each one of these clichéd quotes from the present echoes back into the past, the humor diminishes precipitously. I found myself groaning, feeling that one more “reference” has been checked off the list.

I will not be so crass as to reveal whether or not their beloved Führer and his German shepherd Blondi ever drop in to thank them for their heroic, sacrificial work. I will, however, relate an anecdote I once heard from the renowned Samuel Beckett interpreter Alan Mandell. Mandell and his small team of actors had a contract with the state prison to come in and present Waiting for Godot—waiting obviously a topic of interest to the inmates. At the conclusion the actors hosted a Q&A. Mandell asked, “Tell me, were you expecting Godot to appear?” Immediately a hand shot up and one prisoner called out a strong “No!” “Oh,” said Mandell, “I’m interested to know why you felt so sure of that.” The prisoner answered, “Because there were no other actors listed in the program.”

If you love Beckett because it’s so existential and nothing happens, well, you might like H*tler’s Tasters for the same reason. There really aren’t too many indelible rules for theatre. But one thing I like to see by the end of a play is how the characters—at least one—changes and grows, for better or for worse, and how the lay of the land is somehow different at the end from how it was at the beginning.

As for that * in the play’s title. Is that supposed to mean the name should not be uttered in polite company? I don’t know, it seems performative without signifying anything other than a pretentious nod to the “trigger” factor.

Still, as I’ve said, the cast—Ali Axelrad as Anna, Olivia Gill as Hilda, Paige Simunovich as Liesel, and Caitlin Zambito as Margot—are all so good in their parts. The production values for this really small space are really good (as one would expect from a Rogue Machine offering and from anything connected to Guillermo Cienfuegos): Joe McClean and Dane Bowman (scenic and lighting design), Ashleigh Poteat (costume design), Christine Cover Ferro (costume coordinator), Chris Moscatiello (sound consultant), Carsen Joenk (sound design), Ashlee Wasmund (choreographer), Emmy Frevele (choreography for Rogue Machine).

I wish I could say otherwise, but I just don’t think it adds up in the end.

H*tler’s Tasters plays through June 3, with performances at 8 p.m. on Fri. and Mon., at 5 p.m. on Sat., and 7 p.m. on Sun. (no performance on Mon., May 13). Rogue Machine, in the Matrix Theatre, is located at 7657 Melrose Ave., Los Angeles 90046. Reservations can be secured on the company website or for more information call (855) 585-5185. Recommended for ages 14+.