Unions and strikes do not often appear in mainstream cinema, so as a student of fiction featuring activists and social movements I pay attention when they do. Both Billy Elliot and Pride are set during the pivotal 1984-5 Miners’ Union strike in northern England, where miners struggled for over a year against the implacable Thatcher government to win better working conditions.

Each of these films challenges gender stereotyping in distinct ways. A valuable contribution, but what particularly interests me is that both present up-close views of workers living through a prolonged strike. To what degree are the strikers and organizers shown as multidimensional humans rather than stereotypes? Do these stories increase our understanding and connection to the reality of a union on strike?

In Billy Elliot (2000, Stephen Daldry), eleven-year-old Billy faces disbelief and disdain when his father and brother, both striking miners, discover he’s been learning ballet and wants to be a dancer. The story follows Billy’s father’s transformation as he grows to accept his son’s unexpected talent and struggles to raise tuition money, despite being on strike, to send him to an elite ballet academy.

In Pride (2014, Matthew Warchus), an LGBTQ+ group offers support to the striking miners, seeing them as comrades in suffering and struggle. They discover that the miners’ prejudices and their own false assumptions make cooperation a challenge. The movie follows their poignant and often hilarious encounters as the two groups explore the complexities of solidarity.

In both films, striking miners are central characters, and all involved must battle class and gender-based oppression as well as their own prejudices.

So far, so good. But what impact does each movie have on viewers’ feelings about the workers and the strike?

Billy Elliot: Soaring Dancer, Sinking Union

Young Billy Elliot hates his boxing lessons. He’s fascinated by the ballet class that practices next to the local boxing ring (we’re told the strikers’ soup kitchen displaced the dancers from their usual classroom.) Deceiving his father and brother, Billy cuts boxing and attends ballet with the tutu-wearing girls, becoming the ballet teacher’s star pupil.

The father and brother discover Billy’s secret and pour contempt on him for being a “sissy”–until they see him dance. After they are won over, the story centers on whether Billy will get into a famous London ballet school, and whether the father can afford the tuition.

The movie gives a balanced, sympathetic portrayal of the class tensions that arise between the father (whose poverty we are given to understand is due to the strike) and the middle-class teacher who wants to support Billy’s gift. It adeptly shows Billy wrestling with gender pigeonholes, expressing his conflicted emotions about his relationships with his gay best friend and the ballet teacher’s sexually precocious daughter through his spectacular dancing.

Yet the film squanders its opportunity to humanize a household on strike with the same empathy and gentle humor it bestows on the characters’ efforts to come to terms with Billy’s ballet. Instead, it retreats to stereotypes and othering, depicting the economic hardships of the strike and the bitter strife between strikers and “scabs” in alienating ways that fail to illuminate the conflict, let alone show the incredible heroism of the miners and their families.

Even though the father is a striking miner and Billy’s older brother is a strike leader, we glimpse nothing of the energy, intelligence, and creativity needed to organize and sustain an embattled industry-wide strike. We spend the entire film with these folks, at what turns out to be a crucial moment in their strike, yet we never see the characters engage in ordinary cooperative tasks of organizing, nor in the camaraderie they would certainly show each other much of the time.

Other than a few seconds overheard on somebody’s radio, we viewers get no information about how the Thatcher government and the mining companies constantly attacked the miners and their union, and we don’t hear the workers discuss it. The only clashes we see are miners battling police (with clubbing, arrests, and a very long chase scene) and miners yelling, snarling, and throwing things at strikebreakers. We learn virtually no information or background. Ironically, the only substantive dialog about the strike’s merits is the negative commentary of the ballet teacher’s conservative husband.

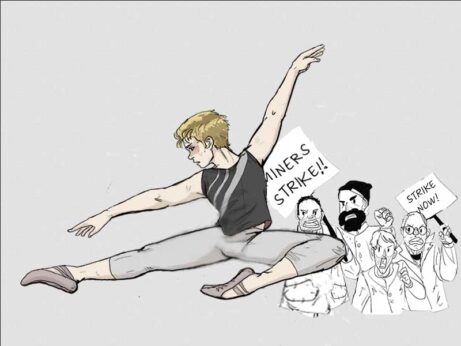

If the film had allowed the workers to clearly express their demands, as they would on any picket line, we could have learned what motivated them. But they don’t even carry signs (unlike in our graphic below). We only hear them monotonously shouting, “Scab! Scab! Scab!”, an epithet many viewers may not even understand, given how little young people are taught about labor struggles, and how infrequently these appear in popular media.

Not to mention the puzzlement we feel at seeing the strikers throw eggs at the strikebreakers’ bus rather than feed them to their hungry children.

At the movie’s end, Billy triumphs as a lead dancer, while the union ignominiously “caves” and is heard from no more.

Pride and the Union

This 2014 film takes a different approach. A group of LGBTQ+ Londoners discuss the miners’ strike and note how they are linked by shared experience of persecution. After the group’s little storefront headquarters is attacked early in the film, they organize—with some internal dissent—Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM). The project raises money for the strikers and eventually makes a journey to the North of England to personally hand the funds to the miners.

In contrast to their negativity and inarticulateness in Billy Elliot, the miners and their families in Pride are vivid, intelligent, sympathetic characters we readily identify with.

The story gives a closeup of interpersonal, organizational, and family struggles among the miners as they confront the hardships of the strike—but unlike Billy Elliot, Pride does not blame or treat the strike and the union as alien forces.

In Pride, we witness conversations and arguments that illuminate the political and social issues the characters are facing. We follow the arc of the encounters between LGSM and the miners as it progresses from bewilderment and rejection to friendship and solidarity, in engaging, often amusing scenes in the miners’ homes and union hall. We see the miners’ views transform when they return the LGSM folks’ visit and glimpse London nightlife, culminating in a drag show fundraiser for the strike, where strike leader Dai steps onstage to raucous acclaim from the Queer community.

Pride illustrates the joys and challenges of building solidarity, and how this process changes people in both groups in ways that go beyond the strike itself.

Fairly Depicting Unions in Fiction

Granted, the themes of the two movies are different: Billy Elliot is about the power of art to overcome preconceptions and stereotypes, with the strike in the background. Nor is Pride exactly ‘about’ the strike, but about how two distinct subcultures overcome deep mistrust to find common ground, support one another’s struggles, and form genuine human connections.

The more individualistic focus of Billy Elliot is not why I think this movie presents a regrettable picture of the workers’ movement. After all, fiction illuminates social issues precisely because it shows them up close, through the struggles of individuals.

The problem is that the union is portrayed as a remote entity, and even though the strike is the setting for much of the film, we learn virtually nothing about its workings, demands, accomplishments, or progress, much less what it feels like to be part of one–because the workers appear to consider it a separate force (exactly what bosses want workers to feel about unions, in fact.) Nor do we learn about the solidarity that linked the strikers from all over England, as well as other supporting groups, including the LGBTQ+ groups that inspired the story of Pride.

Subtle emphasis and de-emphasis matter. In Billy Elliot, scenes of collective support among the miners, like the soup kitchen set up in the ballet classroom that precipitates Billy’s story, are all off-screen, mentioned only in passing. We even learn—if we’re paying close attention—that the union took up a collection to contribute to Billy’s ballet school tuition. The briefest on-screen glimpse of this generous gesture could have somewhat counterbalanced the scenes of workers yelling at each other and would have shown us how not only the father and brother but the union itself experienced transformation by overcoming macho prejudices.

Moreover, unlike Pride, where the union women are as key as the men, in Billy Elliot the women of the strike are simply not present. [For an excellent view of the real role of women in that strike, see Women in the Miners’ Strike, 1985-5.]

Anti-union details sneak past our awareness

Billy Elliot is a heartwarming family/dance film with a positive, progressive message concerning gender norms and the importance of allowing young people to express themselves creatively.

At the same time, many details, impressions, characterizations, and even the bleak color palette and other cinematographic choices, present the union and the strike in a negative light.

I feel that such impressions can be more harmful than an overt anti-union message because devices like those mentioned above play on our ingrained, unconscious stereotypes. The manipulative union; the loutish, inarticulate workers; the strike sowing dissension and causing hardship, are tropes that affect us without our notice. Most likely, the filmmakers weren’t aware they were weaving unexamined prejudices into the story, but that does not excuse them.

Pride is not without flaws in terms of activist representation—the LGSM members are all White, for instance, and the fact that their leader was in real life a socialist is absent in this story, as are other interesting details you can find in this review. And while the striking miners are shown in a much more nuanced and humanizing way than in Billy Elliot, we still don’t learn very much about the strike or its context. I know, a movie is not a history lesson, but a little more info could have been integrated very naturally into a couple of conversations in Pride, as it certainly could have in Billy Elliot.

Overall, however, Pride gives a much fairer view of this epic struggle, ending not with the union’s defeat but with a major London demonstration, with the miners and LGSM marching together amid thousands, leaving us with an uplifting image that reinforces its thoughtful exploration of the complexities and the beauty of solidarity.

So why does this matter?

We need more awareness of how, by erasing and stereotyping activists in fiction, the dominant culture messes with our minds and manipulates us into forgetting, fearing, and otherwise being negatively disposed to what is, coincidentally, the ruling class’s biggest nemesis: working-class organizing!

Reposted by permission from the original in Activist Explorer.