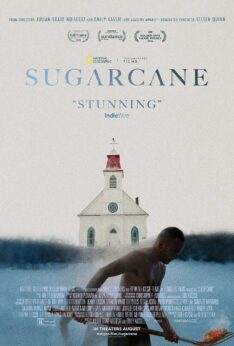

A stunning new documentary film co-directed by Julian Brave NoiseCat and Emily Kassie and produced by National Geographic will open your eyes—and perhaps more importantly, your heart—to the widespread abuse of Indigenous children over the course of a century.

Sugarcane speaks of the hundreds of schools in the U.S. and Canada dedicated to uprooting Indigenous children from their families and culture and instilling “white” European-based religion and values in their young minds. Federally funded, these schools were turned over to religious orders to operate and left to their own devices without supervision by any educational bodies. Priests and nuns were free to exact upon innocent children their vile punishments and perversions, all under a strict code of silence. The objective was explicitly to “get rid of the Indian problem.” Later generations would call that “genocide.”

Only in 2021, with the recent discovery in rural British Columbia of unmarked mass graves of children who had mysteriously gone missing from these schools, has the whole subject of abuse and murder turned into an unstoppable search for answers. “Their ghosts woke a country.”

In Sugarcane we meet the Canadian community of Williams Lake, with a reservation on one side and a Roman Catholic mission school, run by the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, on the other. It finally closed in 1981. Parents were forced to surrender their children from the age of 5 or 6 to boarding school, where they were compelled to obey their Caucasian superiors. They were shamed, told they were dirty, guilty and sinful, and of no inherent human worth. Their people, their culture—all of that was pagan and wrongheaded.

The film introduces us to the survivors of the St. Joseph’s Mission School and the decades-long repercussions of their childhood trauma. We see grown men and women opening old photo albums of their classmates, and one by one the survivor will pick out all the later suicides. In one especially dysfunctional adoptive family to which 11 Native children were sent, seven are known to have killed themselves.

Students were assigned a number and were never addressed by name. Punishment for minor transgressions, like talking out of turn or using the Native language, was severe: beatings to the point of the child passing out on the ropes they were strung up on, and being forced to kneel in place holding a heavy Bible over their head for over an hour, among others.

The priest who took your confession in the morning might come to drag you out of bed that night.

Naturally, some children ran away, and if they got lost in the woods they could freeze to death. If their bodies were found, they’d be committed to the school incinerator and no family members would ever be notified.

Priests had complete control, and sexual violence against both boys and girls was rampant. In some cases, the perpetrator, if reported, would simply be moved away to some other school where he’d be free to resume his atrocities. If young girls became pregnant, they’d sometimes be sent off to a Catholic birthing center in Vancouver, and the babies would be put up for adoption. But just as often, horrifyingly, if a baby was born at the school, it would be placed in a shoebox and burnt in the furnace. In one recalled incident, a young mother at the school accused of “abandoning” her child is convicted and sentenced to a year in jail. The film has witnesses and participants giving testimony for the first time about events they had been forbidden to even whisper about. Says one survivor, “I’ll never forget and it’s pretty hard to forgive.”

These priests had the gall to teach children about sin!

Sugarcane features the dedicated investigators who pore over church and school records, dig up graves, and examine the old obituary pages of the Williams Lake Tribune to piece together the serial crimes committed by the Church and underwritten by the Canadian state. In one scene a tribal elder and his wife are studying the results of a DNA test, which reveals 50% Irish, 5% Scottish, and 45% Indigenous. His closest relatives are members of the McGrath clan. One of the priests at the mission school was Father McGrath. It is a portrait on film of a community forced to reckon with its sordid past.

In the United States, there were 417 such schools. The last one closed in 1997. Estimates are that at least half a million children passed through that system.

Julian Brave NoiseCat, a co-director, stems from Lake Williams insofar as his father, Indigenous artist Ed Archie NoiseCat, was born at the school. In some ways, the film is almost a “road trip” of discovery about the past, and about father-and-son reconciliation. It is also in part a document about current Indigenous practice, all set in an almost pristine landscape marred only by clearcutting for lumber, by the burnt remains from a recent wildfire, and by the slowly decaying school buildings that have fallen into gradual desuetude.

The documentary includes footage shot in the years before the school closed. Children are put to bed in a huge dormitory, reciting the Lord’s Prayer before sleep. In another clip, innocent, trusting children flock around the principal adoringly. How little they knew!

The documentary includes footage shot in the years before the school closed. Children are put to bed in a huge dormitory, reciting the Lord’s Prayer before sleep. In another clip, innocent, trusting children flock around the principal adoringly. How little they knew!

An episode of the film treats the Indigenous peoples’ visit to the Vatican to meet and hear Pope Francis. Will there be an acknowledgment of what was done? An apology? Redress? Reparations? Compensation? Or will it once again, as always before, be swept under the rug never to be spoken of again? The camera does not miss the Native and Indigenous peoples’ stolen artifacts displayed in the Vatican Museum.

It is to the filmmakers’ immense credit that, especially with the cooperation of Julian, they were able to win the community’s trust and gain access to the most intimate stories of their lives.

Indian residential school history and its impact are not in the past. Lives characterized by addiction, a sense of worthlessness, and suicide have been ruined. For more information on the film’s impact campaign, please visit here. For other resources, see the film website.

Sugarcane runs 107 minutes. It is playing in select theaters around the country. The trailer can be viewed here.