Langston Hughes traveled to Haiti in April 1931 and lived in Port-au-Prince for about three months. He observed the ongoing brutal occupation of the country by U.S. Marines, along with the economic exploitation of the independent Black republic by white supremacist nations. In an article for New Masses titled “People Without Shoes,” he recorded the appalling results of both: “A fruit tree for Wall Street, a mango for the Occupation, coffee for foreign cups, and poverty for its own black workers and peasants.”

Arna Wendell Bontemps, born in Louisiana in 1902, grew up in Los Angeles but moved in the early 1920s to New York, where his prizewinning poetry put him at the center of the Harlem Renaissance. In comparison to the trend-setting Harlem literati, Bontemps was not a politically engaged writer. An observant Seventh-day Adventist, he made his living as a teacher at the church-run Harlem Academy. When church authorities became wary of his friendships with leftists like Hughes, they reassigned him, forcing him to move with his family to Huntsville, Ala., to teach at another Adventist school in 1931.

The move backfired, partly because Huntsville is 30 miles from Decatur, where the sensational Scottsboro trials were then in progress, and partly because the radical bad boy Hughes came south to visit with Bontemps during the Christmas holiday. It was during this visit that the two wrapped up their work on Popo and Fifina, a family-centered account of life among working people of Haiti whose ancestors had been brought to the Caribbean nation as slaves. The co-authored book is now regarded as an important African-American narrative and a classic of multicultural children’s literature.

The move backfired, partly because Huntsville is 30 miles from Decatur, where the sensational Scottsboro trials were then in progress, and partly because the radical bad boy Hughes came south to visit with Bontemps during the Christmas holiday. It was during this visit that the two wrapped up their work on Popo and Fifina, a family-centered account of life among working people of Haiti whose ancestors had been brought to the Caribbean nation as slaves. The co-authored book is now regarded as an important African-American narrative and a classic of multicultural children’s literature.

The fact that Hughes collaborated with Bontemps while making side trips to interview the Scottsboro defendants in their prison cells did not go unnoticed. The head of Bontemps’ school, a white man, publicly demanded that the 29-year-old teacher make a “clean break” from worldliness and politics by burning nearly every book he owned. Bontemps was “too horrified to speak.” At once his career took a decidedly leftist turn.

In Popo and Fifina, Bontemps and Hughes artfully soften their political messages for the story’s young audience and its mainstream publisher, Macmillan. Nevertheless, the book’s depiction of dignified Haitians made a bold statement in 1932. That statement is freshly meaningful at a moment when legal Haitian immigrants are being maliciously threatened and slandered for political gain.

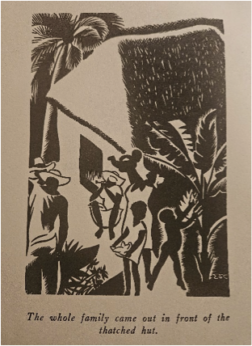

Chapter I of the narrative, “Going to Town,” introduces eight-year-old Popo and his sister, ten-year-old Fifina, who walk behind two long-eared burros loaded with possessions, down the winding high road to the coastal town of Cape Haiti. Led by their parents, Papa Jean and Mamma Anna, they are moving from their grandmother’s home in the country to a new home by the ocean, where Papa Jean plans to become a fisherman. Papa Jean wears a straw hat and white trousers but goes barefoot “like all peasants of Haiti.” Mamma Anna carries baby Pensia swinging at her side as Haitian mothers do. “We’ve got to find a house and get unpacked before night,” says Papa Jean as the travelers start down the hillside.

In Chapter II, the family finds a one-room shack with a tin roof, and Papa Jean strolls out to the beach to talk with the fishermen. Popo watches from a distance as his father talks, making motions with his hands and asking many questions. He returns with some fine red snapper procured from the fishermen.

In Chapter II, the family finds a one-room shack with a tin roof, and Papa Jean strolls out to the beach to talk with the fishermen. Popo watches from a distance as his father talks, making motions with his hands and asking many questions. He returns with some fine red snapper procured from the fishermen.

“When you have your own boat, may I go out with you sometime?” asks Popo. “Of course,” says Papa Jean. “But it won’t be easy to get a boat,” adds Mamma Anna, “We’ll have to work hard.” Papa Jean agrees, “Yes, we’ll have to work and work.” Fifina shouts, “I am willing!” Popo says, “I too.” The title of the chapter is “Work to Do,” and it emphasizes the diligence and resilience of a migrant family.

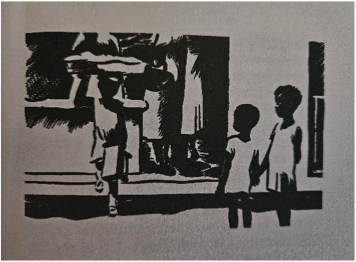

Chapter III, “Running Water,” is about washing clothes and washing dishes. Popo follows his mother and sister to the nearby public washing place. The fountain at the corner is for pots and pans, but it’s better to wash clothes in the sparkling water from the mountain spring, which flows in a little stone gully for the use of people who do not have private wells. Bars of soap are costly, but the leaves of the soap bush, when rubbed between the hands, produce a lather not unlike that of moistened soap. Popo and Fifina earn pennies by scrubbing the large milk cans carried by older women on their delivery rounds, making them “clean and shiny inside and out.”

Ever since Haiti’s successful revolt against French enslavers in the 1790s, and into the 20th century, white historians had maligned Haitians as a barbaric people, and the nation itself as a threat to the U.S. racial order. Part of the purpose of Popo and Fifina is to provide corrective knowledge about a culture often viewed in U.S. political discourse with fear, condescension, and unabashed racism.

Composed by two renowned poets, the lyrical text celebrates the splendor of the Haitian landscape: “Beautiful flowering trees were plentiful, their blossoms red like fire, or white as milk.” Among the wonders of the seacoast, Popo and Fifina discover “a host of red, blue, and yellow parrot fish darting about excitedly,” creatures they deem “too pretty to eat.” Enhanced by 28 lively woodcut illustrations, Popo and Fifina offers a collage of verbal and visual images, each contributing to a sympathetic depiction of an orderly, moral, healthy, and humane collective society with a proud history.

In contrast, the book’s several allusions to U.S. culture prompt uneasy feelings and carry overtones of antagonism. In Chapter V, “A Trip to the Country,” Mamma Anna, homesick for a visit with her family, leads the children through a serene pastoral setting until they pass by “the only important factory of the town, where pineapples are canned and prepared for shipment to the United States.” The many Black men seen working there “did not move about leisurely, like other workers, and Popo thought he wouldn’t enjoy working so hurriedly.”

Later Popo’s family notices several beaches, one of which belonged to the U.S. Marines. “Their bath houses were built near the water, and the water itself was fenced in to keep the sharks away.” Immediately the text seizes on a contrasting image: “Beyond this were the beaches where the people of Haiti bathed. These also were protected from sharks—but not by wire fences built in the water. They were protected by natural reefs, and the seaweed.” Metal barriers protect Americans; nature protects Haitians. This is the text’s only direct mention of the U.S. Marine occupation.

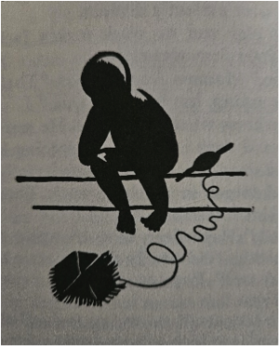

A centerpiece of this culture-based pattern of antagonism comes halfway into the book, when Popo and Fifina, having earned a reward for working at home and for their neighbors, are presented with a beautiful kite, made by Papa Jean in the shape of a bright red star—the emblem of the Soviet Union. At the instant Popo releases the kite, it climbs into the sky, “a big scarlet star rising from the seashore.”

Fifina runs to Popo’s side and together they happily watch the “great red star rise from the white beach.” Tension intervenes when Popo spies another kite in the air, a “strange…dull brown thing” that reminds him of “a hawk swooping over a smaller bird”—an image of imperialist rapacity. The “rude misbehaving” kite attacks, trying to saw across Popo’s string and cut it loose. Popo, believing his kite a match for any hawk, responds confidently to the aggressive maneuver and counterattacks. The hawk kite falls like an “evil bird” while the “big red star climbed the sky proudly, a true conqueror.” In all of American literature, there is perhaps no more interesting symbolization of the zeitgeist of the early 1930s, a confident period in the world socialist movement as the West fell into Depression.

Fifina runs to Popo’s side and together they happily watch the “great red star rise from the white beach.” Tension intervenes when Popo spies another kite in the air, a “strange…dull brown thing” that reminds him of “a hawk swooping over a smaller bird”—an image of imperialist rapacity. The “rude misbehaving” kite attacks, trying to saw across Popo’s string and cut it loose. Popo, believing his kite a match for any hawk, responds confidently to the aggressive maneuver and counterattacks. The hawk kite falls like an “evil bird” while the “big red star climbed the sky proudly, a true conqueror.” In all of American literature, there is perhaps no more interesting symbolization of the zeitgeist of the early 1930s, a confident period in the world socialist movement as the West fell into Depression.

As the scholar/critic Arnold Rampersad noted, Langston Hughes placed an identification with the impoverished masses “at the center of his consciousness as an artist.” His portrayal of the Haitian poor is consistent with a radical socialist worldview. Though he never formally joined the Communist Party, Hughes nudged Arna Bontemps leftward. After Popo and Fifina, Bontemps’ next project was Black Thunder, a historical novel of the Gabriel Prosser slave rebellion that took place in Virginia in 1800 but was inspired by the Haitian revolt led in the 1790s by the Black general Toussaint Louverture. Bontemps’ novel connects Haitian history with African-American history while alluding pointedly to the ideals of the Depression-era socialist movement and its agitation for proletarian revolution.

In the chapter following the kite battle, we learn that Popo and Fifina have been enjoying their kite for several days and have therefore “forgotten all about work.” Popo had “done nothing but play, eat and sleep.” As the children return home with the kite, Papa Jean softly utters a variation of a well-known Welsh proverb: “All play and no work makes Jack a dull boy,” prompting Mamma Anna to comment, “That’s an old foreign saying, but it is very true.”

Papa Jean’s gentle reminder that “maybe a little work would be a change” elicits a quick response: “What can we do to help?” Fifina asks, “We like to work and help.” The interaction is in keeping with the book’s portrayal of the central characters as possessors of a strong work ethic. Likewise, Popo is more than once advised, “You better be getting to bed…to be up early in the morning.” This variation of Benjamin Franklin’s “early to be bed, early to rise” aphorism transplants Franklin’s formulaic proto-capitalist values—a bedrock American ideal. Hughes and Bontemps give a Haitian face to the disciplined economic striving Americans associate with hard-working migrants.

Papa Jean’s gentle reminder that “maybe a little work would be a change” elicits a quick response: “What can we do to help?” Fifina asks, “We like to work and help.” The interaction is in keeping with the book’s portrayal of the central characters as possessors of a strong work ethic. Likewise, Popo is more than once advised, “You better be getting to bed…to be up early in the morning.” This variation of Benjamin Franklin’s “early to be bed, early to rise” aphorism transplants Franklin’s formulaic proto-capitalist values—a bedrock American ideal. Hughes and Bontemps give a Haitian face to the disciplined economic striving Americans associate with hard-working migrants.

Booker T. Washington’s classic salvational autobiography, Up from Slavery, had likewise repeatedly alluded to Franklinian philosophy to align its protagonist within mainstream Americanism—a strategy that encouraged readers to transcend racial barriers and identify with the formerly enslaved as citizens. In a similar way, Bontemps and Hughes encourage U.S. audiences to identify with the family of Popo and Fifina.

The salvational autobiography genre also typically doubles as a bildungsroman or novel of education, in this case focusing on the maturation of Popo. In Chapter IX, “A Job for Popo,” it is time for Popo to have “a real job.” Still too young to fish with his father, a skill he will learn later, Popo apprentices at the cabinet shop of his Uncle Jacques, working alongside “old man Durand” and his cousin Marcel, a boy of nearly the same age, to learn the trade of woodworking.

Unlike Franklin’s soulless model, the work consists of more than utilitarian physical labor. It is based on a family bond and encompasses a spiritual component that is at least as important as the economic. Observing the making of ornately decorated trays, Popo notices that every tray is unique and asks Durand how he is able to create a different design each day. The wise worker explains:

You have to put yourself into the design.… What you see leaves a picture…. Some pictures make me glad…. Some pictures make me weep inside…. Not thought, but what I am inside makes the design.… The design is me…a picture of the way I feel…. When people look—they will feel as you felt…. That is really the only way that people can ever learn how other people feel.

“It’s wonderful,” says Popo. He is “so excited and happy that he could not speak.” He imbibes not only the business side of woodworking, but the spirit of the artist who expresses himself through work—a sophisticated lesson about creativity and what makes us human.

“It’s wonderful,” says Popo. He is “so excited and happy that he could not speak.” He imbibes not only the business side of woodworking, but the spirit of the artist who expresses himself through work—a sophisticated lesson about creativity and what makes us human.

There is one more key scene. While at work in the shop, Uncle Jacques, a master storyteller, passes on a fundamental episode of the Haitian oral tradition. He tells the boys about the origin of “the great stone fort called the Citadel of King Christophe, on the high, far-away mountain overlooking the town of Cape Haiti.” The grandfather of Uncle Jacques had seen the Black workingmen drag a great large bronze cannon through the streets and up the steep sides of the mountain, tugging and pulling. Once, he had seen Christophe, the king who was responsible for the huge structure, as he passed through town “on a white horse, surrounded by bodyguards in flashing uniforms.”

Popo begins to understand that the Haitians had been slaves—brought by the French to the colony from West Central Africa and the Bight of Benin. They “had freed themselves, fighting. Then they had built that fort, the Citadel, as a protection, so that the French might not come and make them slaves again. That was why the men worked so hard.”

Immediately Popo’s thoughts turn to the tray he is crafting and embellishing. Beyond simple edification, the story has elevated his feelings. He is newly committed to finishing his work without delay. The boy thinks of what old man Durand had said about a design being a picture of how you feel inside. He wonders if his tray will show his silent sadness about King Christophe and Haitian history.

One definition of art is pain transformed into beauty. As Popo puts the finishing touches on his tray, he feels as if he could cry. His uncle tells him that he’ll make many beautiful things when he’s older. Old man Durand urges him to remember “the riddle about putting yourself into your designs.”

The final chapters of Popo and Fifina are essentially the corrective rewriting of a historical account published by the British white supremacist Hesketh Prichard in 1900 in his racist history of Haiti, Where Black Rules White. Prichard’s haunting chapter, “The Citadel of the Black Napoleon,” emphasized only Christophe’s “self-seeking, corruption and cruelty” and viewed the Citadel as evidence of monstrosity rather than masculine accomplishment.

Upon its publication in July 1932, Popo and Fifina was welcomed by librarians and newsworthy enough to be reviewed in the New York Times. “Here is a travel book that is a model of its kind,” wrote children’s editor Anne T. Eaton. “Facts, indeed, the reader acquires, but unconsciously, for what he feels is the atmosphere of Haiti, dusty little roads that wind along the hills, sun-drenched silences only broken by the droning of insects and the cry of topical birds, silver sails on clear green water, sheets of warm white rain. Popo and Fifina tempts us to wish that all our travel books for children might be written by poets.”

The Times reviewer mused not at all about the accomplishment Hughes and Bontemps may have been most proud of—that of favorably inscribing Haiti into U.S. culture, if only by means guardedly political and subliminal.