LOS ANGELES — Renowned, revered writer and activist Jesús Colón (1901-74), remembered as “Father of the Nuyorican Movement,” stars as the central character in The Red Rose. The musicalized version of Colón’s life is offered by The Bronx’s Pregones/Puerto Rican Traveling Theater, one of 19 theater companies involving 165 artists from across the U.S. and Puerto Rico, currently electrifying downtown L.A. during a three-week national festival of dynamic, contemporary Latiné theater. Encuentro 2024: We Are Here–Presente!, sponsored by the Latino Theater Company at the Los Angeles Theatre Center, runs through Nov. 10. We reviewed another festival play, Odd Man Out, on Oct. 30. The last two performances of The Red Rose take place on Sat., Nov. 9, at 4 and at 8 p.m.

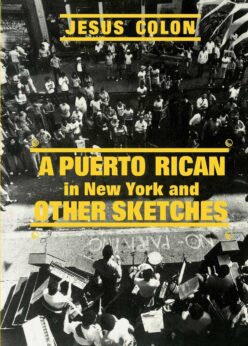

A biographical sketch of Colón in People’s World in 2006 mentions that The Red Rose dates back to the year before that. That same article includes two complete stories from his A Puerto Rican in New York and Other Sketches. A reading of his New York subway incident, “Little Things Are Big,” incorporated verbatim in the play, can be heard here.

The Red Rose, winner of HOLA and ACE awards, performed in English and Spanish, with Spanish and English supertitles, reminds theatergoers of this foundational writer and uncovers a little-known chapter in the history of the McCarthy-era Red Scare. The text is adapted both from Colón’s own writings and from the court record of his 1959 hearing before the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

The star witness in that infamous hearing was infiltrator and undercover NYPD/FBI agent Mildred Blauvelt, who successfully posed as Sylvia Vogel for nine years. She named names of all the Puerto Rican and other Latiné Communists and “fellow travelers,” in the Puerto Rican Communist Party club named for La Pasionaria, both in New York and back home in “the colony.” We see her in an earlier scene suggesting to the Colón-founded Puerto Rico Civic Center that the educational and improvement group conduct a wide-ranging survey of workplaces and neighborhoods to assess community needs—and sell the Daily Worker—which we retroactively recognize, of course, as the FBI trying to gather as much information as possible about activists, malcontents, organizers, sympathizers, and folks who are interested in the paper. Recounting years of meetings, rallies, and club organizing, even recruiting others to the Party, and late evenings communicating her detailed reports to the police, she was the first woman to earn the agency’s Exceptional Service Award (for spies and stool pigeons).

I don’t know of another all-dancing, all-singing American musical that includes as a cast member the courageous lawyer for many of the “unfriendly witnesses” before HUAC, Richard Arens. The interrogator persists in addressing the witness as “Jeezus” Colón, indicating, by his conscious mispronunciation, his contempt for any culture and language other than his own. In our own day, needless to say, we’ve witnessed the same insulting phenomenon regarding our sitting Vice President Harris. Other characters play the parts of judges, interrogators, and lawyers at Colón’s hearing. A whole musical number urges the witness to “Take the Fifth” (Amendment)—“La Quinta”—in his own constitutional defense.

Another amusing episode in the play involves another “Fifth,” a surprising one, but fitting. It’s the story of Colón’s comrade Sarah, a Lithuanian Jew, who toward the end of her life gives him her precious mandolin and evokes memories of the great mandolin orchestra she used to play in. Such ensembles were the hallmark of groups like the IWO (International Workers Order), which also had choruses, theater groups, summer camps, housing co-ops, classes, and fraternal benefit programs for its members, part of an embracing Communist culture similar to a number of immigrant, religious and rival socialist organizations (such as the Workmen’s Circle). Her orchestra once performed—it was the high point of her life—the entire Beethoven Fifth Symphony, recapitulated here by a terrific four-piece band. She interprets each movement as the German Romantic composer’s striving for liberation and the ultimate victory of socialism. At the end of the play the band and chorus erupt in another classical music superhit, Händel’s “Hallelujah” Chorus, with new emancipatory words celebrating the working class.

The introduction of such works, alongside the storytelling through the Puerto Rican musical genre the plena, fits the subject well, for even in the first moments of the play we find Colón in his New York room writing a letter back to his beloved Conchita in PR, and he’s just been reading Montaigne. He had also taken two years of law school, though he did not graduate. Nevertheless, with the Latin penchant for glitter, aggrandizement and exaggeration (there’s a whole number on this), his friends called him “The Lawyer” all his life. Colón, like his Jewish friend Sarah, are models of the self-made empathic proletarian intellectual equally at home with organizing labor unions and discussing erudite philosophy.

This amazing work, 105 minutes long, with one intermission, musicalizes Colón’s life, with a deep focus on his great love for fellow Puerto Rican Conchita. After her early death, he married again, to Carmela, another woman from PR. We learn of the many trades and degrading jobs he worked at in his younger years after landing in New York City in 1917. There’s a whole musical number, “Down Below,” devoted to the “scalers,” the men who cleaned the freezing engine rooms of cargo ships after each voyage. A shift on this job in the hull would leave them covered with grime, oil, and dirt, but it paid better than other jobs a deck or two up. For a number of years, Colón worked for the Post Office, which prompted the investigators to claim he was “disloyal,” as a Communist, to the U.S. government. Late in life, he became a popular staff writer for the Daily Worker with his vernacular stories of life in the lower depths of immigrant life that readers of all ethnic backgrounds could relate to.

An entire scene in the musical dramatizes his fantasy on cucarachas, the cockroaches that infest just about every building and apartment in New York and that are so notoriously difficult to get rid of. Eventually, Colón discovers the way to banish them forever, at least in his own mind. Inspired by a passage from Machiavelli’s The Prince, he encourages the cockroaches in the closet to hate other castes and races—the bread, stove, sink, and garbage cockroaches—and they all form opposing groups with fancy organizational titles. In the end, learning disunity, pride, envy, hypocrisy, and mutual hatred from the human race, they fight each either into extinction! Colón’s imagination, a product in his time of the dangers of nuclear annihilation, is cleverly put to societal use. The dance of the dying cockroach is considerably less famous than Camille Saint-Saëns’ dying swan, but it sure is a lot more fun to watch!

The band includes the composer Desmar Guevara as musical director, along with Álvaro Benavides, Camilo Molina, and Sergio Reyes. It took me a while, but as I was listening to this enchanting score, I realized I had a broad smile on my face almost the whole time.

The seasoned cast of six master performers features José Joaquín García as Jesús Colón and Mario Mattei as Colón’s sometimes nom de plume Miquis Tiquis. Also Anna Malavé as Conchita, Jenyvette Vega as Sylvia, and John Cencio Burgos as Richard Arens. All play other minor roles as well and are members of the dance and choral ensembles. The score is replete with gorgeous Latin singing, surprising harmonies, and quick changes. A special acknowledgment goes to Raúl Abrego for his set design and the colorful projection design by Eamonn Farrell, which contribute so much to the sense of time and place. The writer of The Red Rose is Rosalba Rolón, who also directs.

The seasoned cast of six master performers features José Joaquín García as Jesús Colón and Mario Mattei as Colón’s sometimes nom de plume Miquis Tiquis. Also Anna Malavé as Conchita, Jenyvette Vega as Sylvia, and John Cencio Burgos as Richard Arens. All play other minor roles as well and are members of the dance and choral ensembles. The score is replete with gorgeous Latin singing, surprising harmonies, and quick changes. A special acknowledgment goes to Raúl Abrego for his set design and the colorful projection design by Eamonn Farrell, which contribute so much to the sense of time and place. The writer of The Red Rose is Rosalba Rolón, who also directs.

Colón’s book A Puerto Rican in New York and Other Sketches, a 1984 Before Columbus Foundation American Book Award winner which continues to be read, especially in college Latiné history and culture courses, is still available from International Publishers. Order here.

The Los Angeles Theatre Center is located at 514 S. Spring St., Los Angeles 90013. Parking is available for $8 with box office validation at the Los Angeles Garage Associate Parking structure, 545 S. Main St. (between 5th and 6th Streets, just behind the theater); and buses and Metro also serve the area well. For more information and to purchase tickets, call (213) 489-0994 or go to www.latinotheaterco.org. Click here to view the performance schedule.