FROSTBURG, Md.—People’s World reporter Tim Wheeler shared the podium with Dr. David Gillespie at an April 9 celebration of the founding of the George A. Meyers Collection at the Lewis J. Ort Library at Frostburg State University (FSU). Dr. Gillespie is the retired director of the Ort Library. In honor of the occasion, Wheeler read from No Power Greater: The Life & Times of George A. Meyers, recently published by International Publishers.

They were welcomed by Ort Library Director Randy Lowe, who said he met George A. Meyers once back in 1997. “I think he asked me where the bathroom is,” Lowe quipped to laughter from the crowd. Lowe said this library is the proper place to preserve the history of both Meyers and two U.S. Senators, J. Glenn Beall, father and son, both lifelong residents of Frostburg.

In the crowd were FSU students, faculty, and library staff, residents of Frostburg and Lonaconing, a carload of members of the Maryland Communist Party, and a nephew of George A. Meyers. Wheeler autographed copies of his book and donated the proceeds to the fund that sustains the George A. Meyers Collection.

Archivist Liza Zakhrarova, who organized the event, introduced both speakers. Gillespie, then director of the Ort Library, told the crowd it has been 34 years since Meyers’ sisters, Mary and Catherine Meyers of Lonaconing, met with him in 1991. “Mary told me they had a brother who was a labor organizer at Celanese. He has a very large book collection. That’s the power of sisterhood. It didn’t take much to convince George that his books should come here.”

A few weeks later, George himself visited. “I found out his father was a coal miner. My father, too, was a coal miner. We hit it off! George told me, ‘Maybe I can get Tim Wheeler to come with me next time, and he can write an article that will help get the ball rolling.’”

And roll it did! Art Perlo donated the papers of his father, Marxist economist Victor Perlo, to the Collection. Meyers’s best friend, African American steelworker Joe Henderson, donated his collection. Gillespie told of receiving a phone call from lawyer Tom Kapantais, donating his collection. “I asked him how many books. He told me I better rent a truck.”

Gillespie drove with two muscular FSU staff workers to Huntington, West Virginia, and retrieved Kapantais’s entire library, “8,600 pounds of books, close to 7,000 individual pieces. We stopped at a weigh station on the way back,” Gillespie said. It weighed over four tons.

The George A. Meyers Collection of Marxist, labor, civil rights, and peace literature rivals other left-progressive book collections, including the Tamiment at New York University, the Walter P. Reuther Collection at Wayne State University, and the Harry Bridges Collection at the University of Washington. It includes Communist and Socialist books, pamphlets, leaflets, and other literature. Especially awesome, he said, is the collection of pamphlets with four or five requests each week from other libraries and researchers seeking these rare treasures of the class struggle some of them more than a century old.

Wheeler explained that Meyers was the son of a United Mine Worker coal miner, born in Lonaconing about six miles down Georges Creek from Frostburg. He organized the 10,000 workers at the Celanese synthetic textile mill near Cumberland into Textile Workers Local 1874. He was elected President of the Maryland-D.C. CIO and joined the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) in 1939. He served in the U.S. Army Air Corps in the war to defeat Hitler’s fascism.

Millions of workers flooded into the CIO, in Meyers’s early adulthood, elected Franklin Roosevelt, pushed through the New Deal, the eight-hour day, minimum wage, and the first laws against racist job discrimination. The National Labor Relations Act was passed. Social Security was enacted. Hitler was defeated abroad.

Wheeler said Meyers was in the thick of building that grassroots coalition, a United Front, winning huge victories over the fanatic opposition of the most reactionary, entrenched corporate financiers. But after WWII, corporate America was determined to crush the coalition, especially the CIO, Wheeler said. Their weapon was anti-communism and its evil twin, racism, to target left-progressive leaders in the labor movement, like Meyers himself. Wheeler’s book quotes extensively from Meyers and United Mine Worker President John L. Lewis that the passage of the Taft Hartley Act was corporate America’s “declaration of war on the labor movement.”

Wheeler read from the chapter in his book about Meyers’s arrest, together with other leaders of the Maryland Communist Party, in his tiny apartment in downtown Baltimore. He was changing the diaper of his infant son, Douglas when the FBI came crashing in. His terrified daughter Barbara, then a little girl, burst into tears.

Years of witch-hunt hearings led to thousands of workers, scholars, and other progressives being blacklisted, fired, and unable to find jobs. The CIO and all left-progressive unions were smashed.

Meyers served 38 months in prison on false charges of advocating overthrow of the government by “force and violence.” He was one of many leaders of the CPUSA who served long sentences under the Smith Act, later ruled unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court.

After his release, Meyers spent the rest of his life working to rebuild the labor movement, rebuild the Communist Party, and expose and defeat the “class partnership” hoax foisted on the labor movement by AFL-CIO President George Meany. Meyers saw in the rank-and-file movement, the formation of the Black Caucus in the United Auto Workers, a strategy to break the grip of “class partnership” advocated by AFL-CIO President George Meany and restore “class struggle” trade unionism that inspired the CIO.

Ronald Reagan’s mass firing of 16,500 air traffic controllers brought that struggle to a head. Meyers crisscrossed the nation promoting the idea of a mass march on Washington—Solidarity Day. It took place on Sept. 19, 1981, when 500,000 union members converged on Washington D.C., demanding a halt to Reagan’s union busting.

“As I was working on this book, I kept asking myself: Where was George on Solidarity Day?” said Wheeler. “I knew he must have joined that labor march. He wrote a glowing report about the march, quoted in my book. But where was George?…. I found a photo in the George A. Meyers Collection upstairs in this library, George and Allie marching in the Solidarity Day parade.”

Wheeler opened the book and held it up to show the photo. “It’s not a very good photo. But you can see a woman embracing George. And on the back of the photo, George has written that Allie did not mind the woman embracing him because she is smiling.” Wheeler spent a week retrieving basic source materials from the George A. Meyers Collection last year, assisted by Archivist Zakharova.

Said Wheeler, “Libraries are not considered hotbeds of radicalism. Yet that is what we are up against right now. The Administration in Washington seeks to cleanse our minds, remove literature that promotes social change, abolish diversity, equity, and inclusion.” Again, he held up his book. “There are many pages in this book dedicated to libraries and librarians.”

Wheeler read from a chapter, “Born Free & Everywhere in Chains,” about George A. Meyers’s visit to the Cumberland public library in 1931, where he was greeted by the chief librarian, Mary Walsh. He told Walsh he no longer believed in God but was searching.

Walsh led George into the stacks. The first book she handed him was Famous Utopias, containing Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Social Contract. Then, she handed him Das Kapital by Karl Marx. Meyers read both avidly. He often spoke of Rousseau’s charge that private property is the weapon of greed that enslaves humanity. It was an insight that changed Meyers’s life forever.

“Was Mary Walsh a socialist? A communist? A rabble rouser? No. She was a librarian. She believed in freedom of thought. She wanted to open people’s eyes. She wanted them to read. And now we have an Administration in Washington that bans books, wants to burn books!” Wheeler thanked David Gillespie and the library staff for their courage in creating the George A. Meyers Collection and adding his book to their stacks.

An enormous grassroots movement has sprung up to defend democracy and benefits like Medicaid, Medicare, and Social Security from Trump and Musk, Wheeler noted. He cited the hundreds who joined the “Hands Off!” rally outside the Social Security Administration on the west side of Baltimore on April 5 and over 100,000 who rallied at the base of the Washington Monument that same day to blast the Trump administration—over two million protesters across the nation. The aim, he said, must be to rebuild the United Front movement led by George A. Meyers in the 1930s and 1940s.

He read a story he had covered in 1999 headlined, “Ashes From the Summit of Dan’s Mountain,” about a Catholic Mass for George A. Meyers at St. Mary of the Annunciation in Lonaconing a few days after George died in Baltimore. This is the church where Meyers served as an altar boy and his mother, Kate, sang in the choir. The story quotes Sister Marietta Culhane, Pastoral Life Director of the church, who told the crowd she was proud to have met and befriended George A. Meyers. “He lived to the full extent the Christian social principles that our church embraces. He cared about workers, the poor, and the oppressed. He cared about the rights of Black people. He marched to a different drummer. He was an outstanding Catholic man, and we honor him.”

Earlier, Andrea Bowden, a native of Lonaconing, drove Wheeler to the Allegany County Miners’ Memorial in Frostburg that honors the 713 coal miners who died in mine roof falls, including George A. Meyers’s uncle, Frank Meyers, who died in a mine cave-in when he was 15 years old.

It was his last day before he quit, planning to attend a Catholic seminary to become a priest.

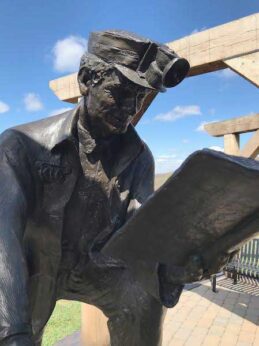

A grassroots committee spearheaded by retired truck driver Bucky Schriver of Midland built the memorial beside the CSX railroad tracks with a sweeping view of the surrounding mountains and valleys. The centerpiece of the memorial is a coal miner in his miner’s overalls, wearing a helmet with a headlamp. In one hand, he is holding out an apple, as if to a teacher. In the other, he holds a book. He is reading. It symbolizes coal miners’ role in donating tens of thousands of dollars from their wages to buy the land and build Frostburg Normal School to train the daughters of coal miners to be school teachers.

George A. Meyers’s sister, Mary Meyers, graduated from Frostburg Normal School and became a beloved classroom teacher. It is now Frostburg State University.