LOS ANGELES — Just about the highest praise I could heap on Larry Muhammad’s Last Night at Mikell’s is that it was well worth enduring the pre-curtain bother and wait to experience it. I’ll spare the details about the hectic opening night performance on Sat., April 19, but suffice it to say, about 35 minutes late, Last Night at Mikell’s commenced.

This stellar production proved, as said, to be well worth the inconveniences. With a bar, tables, chairs, and a stage, the set was designed by Grant Gerrard to look like the eponymous legendary nightclub on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, where most of the action takes place. A montage or mosaic of images (designed by Vanessa Fernandez) projected on the walls mostly featured outstanding African American artists, including John Coltrane, Lena Horne, Sly Stone, Amiri Baraka, Toni Morrison, et al., imparting the sense that this jazz club is a cultural gem.

The real-life Mikell’s, perched at the corner of 97th St. and Columbus Ave., was indeed a beloved hangout for the Black literati and musicians. The play begins, presumably in the 1980s, with James Baldwin (Julio Hanson) bumping into fellow scribe Maya Angelou (Raquel Rosser) on an Upper West Side street. Delighted to see each other, they head over to Mikell’s to catch up, as Baldwin, who was born and raised in Harlem, has just returned home from one of his many jaunts overseas for some R&R—although being a so-called “Native” New Yorker myself, it seems that NYC is a most unlikely place for what that immortal philosopher, Elmer Fudd, called, “At wast, west and wewaxation.”

Hoping to meet up with “Jimmy,” trumpeter Miles Davis (Nick Gillie) has already gone to their favorite haunt, only to find the doors to Mikell’s inexplicably locked. When James’ younger brother, Mikell’s bartender David Baldwin (James T. Lawson II, son of the Civil Rights icon), finally reluctantly opens the doors, only to find out it’s the jazz legend who has been banging on them, he lets the regular enter, but informs Miles that this is the titular last night at Mikell’s.

Gentrification is chasing the nightclub out of business, and combined with the appearance of Maya and the newly returned Jimmy, the trio plans to make a night of it, celebrating Baldwin’s reappearance in NYC and mourning the closing of the popular club. Over the course of the night, it turns out that Baldwin is fatally ill, and the play imagines this final meeting of the minds at their beloved gathering place.

Guillory expertly helms the quartet of thesps, who all deliver outstanding performances that bring their respective historical characters vividly back to life. Based on whatever I knew of the authors and musician, I found all four portrayals realistic and convincing.

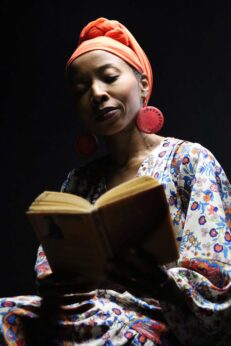

Raquel Rosser excels as Maya and renders a beautiful version of Angelou’s poem “And Still I Rise” as a monologue. Her exposed muscular throat, which is bare (costumes designed by Naila Aladdin Sanders), enhances her finely honed acting. I don’t have a fixation on necks and rarely, if ever, mention them in reviews, but she’s such an exceptional actress that even Ms. Rosser’s neck gets into the act, exuding her intensity. Modigliani would have had a field day painting it, and casting directors and agents should pay attention to this gifted artist.

As Baldwin, Hanson imparts a realistic sensibility about the writing life, and there is a wonderful monologue about what most freelance writers have to contend with from editors and publishers who, like God, often work in mysterious ways.

Having said that, for some reason, this play looks down on Baldwin’s writing a piece for the New York Times: I assure you, most freelance journalists would not sneer at this opportunity, but would likely be pleased to write for the newspaper of record, which confers prominence and presumably decent literary rates.

Baldwin’s obsessive scribing is ascribed to being what’s driving him to an early grave. But to be sure, his heavy smoking and drinking took its toll on the literary titan who was, alas, when all is said and done, just a mere mortal who should have taken better care of himself. Unfortunately, Maya’s character repeats her admonition against Jimmy working too hard ad nauseam, and it becomes tiresome to hear this frequent refrain, which makes Angelou sound like a nag. (It’s the playwright responsible for this repetitiousness, of course, not Ms. Rosser, who is merely reciting the lines and playing the part that has been written for her.)

Last Night at Mikell’s premise put me in mind of One Night in Miami, which was inspired by what really happened after Cassius Clay (later Muhammad Ali) won the heavyweight boxing championship on Feb. 25, 1964, and went back to his Florida motel with other Black notables, singer Sam Cooke, actor/athlete Jim Brown, and activist Malcolm X. While it’s known that this actually took place, nobody really knows for sure what these four iconic men said or did that one night in Miami. In his alternate history, One Night in Miami, playwright Kemp Powers brilliantly conjured up what he imagines may have transpired in his gripping play, which I saw at its 2013 Rogue Machine premiere.

At the afterparty, Larry Muhammad told me that while Mikell’s was a real nightclub, the closing night dramatized onstage with Jimmy, Maya, Miles, and David never happened—except in his imagination. Indeed, Baldwin died in 1987, and Mikell’s closed its doors four years later, so the story as presented could not have taken place. I surmise that the title Last Night at Mikell’s likely has a deeper metaphorical meaning, perhaps about an era of Black culture, or Jimmy’s demise in particular.

Autocratic auto-da-fé versus autobiography

I also asked Mr. Muhammad what he thought about reports that as part of the Trump junta’s anti-DEI drive in the military, the Secretary of Offense had Maya Angelou’s 1969 autobiographical I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings purged from the US Naval Academy library—although two copies of Hitler’s maniacal Mein Kampf were permitted to stay on the library’s shelves.

The bard laughed and went on to say, “I wouldn’t be surprised. Elon gave the Nazi salute. He’s an Afrikaner, from a different time [when South Africa was still an apartheid state]. It’s time for artists to stand up for truth, justice, and the American way,” Mr. Muhammad declared.

I also asked Ms. Rosser about that banning of the book by the character she plays from military libraries, while der Führer’s murderous Mein Kampf remained. “It’s atrocious,” the actress who channeled Angelou stated. “It’s a sad society. Nothing surprises me. Does MAGA know what it means? They replace something about love with hate. It’s very interesting,” Ms. Rosser lamented.

The Orwellian Trump regime may attempt to expurgate history from schools and libraries, etc., but as long as we have courageous theaters such as Robey and plays like Mikell’s dedicated to using the First Amendment to tell the truth, the Trumperialists won’t prevail. The one-act Last Night at Mikell’s is about 90 minutes long, performed without an intermission, and not for the kiddies.

This drama, inspired by real life, is for theatergoers interested in African-American themes, LGBTQ subject matter, insights into and examinations of what makes artists tick, the prominent personalities depicted, and for audiences who just love great acting and writing.

Last Night at Mikell’s is being presented by The Robey Theatre Company through May 11 on Thurs., Fri. and Sat. at 8 p.m., and Sun. at 3 p.m. at the Los Angeles Theatre Center, 514 S. Spring Street, Los Angeles 90013. For info and tickets, call (213) 489-0994 or go to the company website.