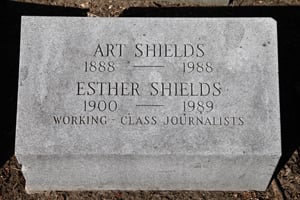

Art Shields was the Daily Worker’s greatest labor reporter. I got to know Art and his wife Esther, herself a labor journalist, soon after I joined the staff of the Worker in January 1967. Art helped me hone my writing skills. He was a role model in his loyalty to workers and their struggles. A tall, lean, strikingly handsome man, he was quiet spoken and modest to a fault. But he was also a superb storyteller.

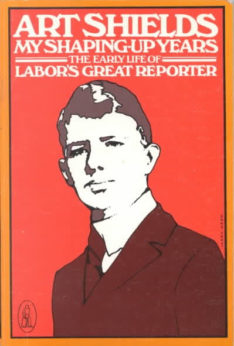

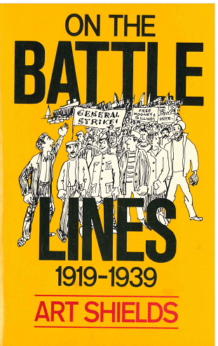

To write this appreciation, I relied on my personal memories, an interview with steelworker George Edwards, one of Art’s close friends, and a re-reading of Art’s remarkable two-volume autobiography, “My Shaping Up Years” and “Battle Lines: 1919-1939.”

To write this appreciation, I relied on my personal memories, an interview with steelworker George Edwards, one of Art’s close friends, and a re-reading of Art’s remarkable two-volume autobiography, “My Shaping Up Years” and “Battle Lines: 1919-1939.”

Telling labor’s untold story

Art was born in Barbados in October 1888, son of a Moravian church preacher. He tells of his first encounters with socialism, hearing Jack London speak at his York, Pa., high school. A year later, Art was working in a machine shop, and a fellow worker urged him to become a socialist.

Art was an early convert to the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). He traveled widely, immersing himself in the class struggle wherever he went. This hobo spirit permeates Art’s writing as it did much of working-class culture in those days. Workers were moving restlessly across the nation seeking work in factories, mines, transportation, and agriculture. It was a time of rising class consciousness. A spirit of defiance, a confidence that ordinary women and men can change the world, animated the movement in those years. Even in the face of the darkest, most brutal repression, workers, united, were invincible.

1919: Revolution in Seattle

That spirit reached a new high when the Russian Revolution erupted in 1917. Art was in Nome, Alaska, drawn by the Gold Rush. Nome was a hotbed of IWW radicalism, and he and his fellow workers convened a rally to celebrate the storming of the Winter Palace. Art never wavered in his solidarity with the world’s first socialist country.

That spirit reached a new high when the Russian Revolution erupted in 1917. Art was in Nome, Alaska, drawn by the Gold Rush. Nome was a hotbed of IWW radicalism, and he and his fellow workers convened a rally to celebrate the storming of the Winter Palace. Art never wavered in his solidarity with the world’s first socialist country.

Two years later, Art was in Seattle. The First World War was still raging and he joined the Army, not to fight in Europe, but to organize antiwar resistance from within as Bolsheviks had done so successfully in Russia. He was felled by the great flu pandemic, which killed two of his brothers and nearly killed him. He was mustered out of the Army.

Art found work as a lathe operator at a shipyard in Seattle. He came to the Machinists Union hall one day in his Army uniform. The lodge president recruited him to deliver a speech calling for a general strike and urging the thousands of Army veterans to support it. Art wrote a leaflet calling for the strike. Twenty thousand were distributed under the slogan, “Together We Win.”

The Seattle General Strike of 1919 idled the city for five days. “Seattle became the quietest city in the United States,” he wrote, “the first mass demonstration of interracial unity I had seen.” In this case, it was not white, Black and Latino workers who gave it the strength of racial unity, but rather Japanese American and white workers who threw their full support to the mass walkout.

IWW leaders of the strike hoped it would spread into a nationwide general strike demanding freedom for labor frame-up victims Tom Mooney and Warren K. Billings. About this same time, Seattle dockworkers refused to load a ship carrying weapons for Kolchak’s counter-revolutionary army in Siberia. It showed just how deep support for the Russian Revolution was among workers. The strike ended with important gains for workers in the Pacific Northwest.

Save Sacco and Vanzetti!

Art traveled back to New York City in 1920. Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, head of the Worker’s Defense Union, asked him to start a publicity campaign to save Sacco and Vanzetti. He went with a young African American attorney, William L. Patterson, to Boston. Art interviewed the two defendants in prison and wrote a pamphlet, “Are they Doomed?”

Vanzetti, an Italian-immigrant fishmonger, was going door to door selling fish the day an armored car was held up 20 miles away. Several guards were killed in the incident. Shields retraced Vanzetti’s steps, interviewing customers who fully corroborated his alibi. But the ruling class was determined to send a message to the growing left-wing workers’ movement, and the two were executed, martyrs of A. Mitchell Palmer’s “Red Scare.”

The Sacco and Vanzetti frame up is echoed today in the ultra-rights drive to criminalize immigrant workers and conversely the struggle by the AFL-CIO and other labor and progressive forces to win legalization for undocumented workers and full workplace and civil rights for all immigrant workers.

As a reporter for the labor-based Federated Press, Art was assigned to West Virginia to cover the 1921 coal miners’ strike. He reported on the trial of miners arrested in Matewan following the murder of pro-miner Sheriff Sid Hatfield by Baldwin Felts gun thugs. That massacre triggered the “Battle of Blair Mountain,” when 5,000 coal miners attempted to march into Mingo County to organize the miners. Five thousand Baldwin-Felts gun thugs, dug in on Blair Mountain, attempted to block their way. The mine owners even used planes to drop crude bombs on the advancing miners.

The miners were winning until President Warren Harding sent 2,000 U.S. troops. Billy Mitchell, commander of the Army Air Corps, had readied 13 Army planes with gas bombs and fragmentation bombs to drop on the miners if they did not halt their advance.

That rather incredible chapter in American history was largely forgotten until West Virginia mine owners recently attempted to decapitate the crest of Blair Mountain in their crazed “mountaintop removal” mining method. So far, a determined fight-back has saved Blair Mountain.

Which side are you on?

In Appalachia, Art’s love of industrial workers, especially coal miners, reached full flower. He was entranced by the beauty of the mountains and with the culture of the people. Among his dearest friends were Florence Reece, who wrote the immortal “Which Side Are You On,” the mountaineer poet Don West, and George Meyers, son of a coal miner from Lonaconing, Md. George later became president of the Maryland-D.C. Congress of Industrial Organizations. Later, George became a much-loved chairman of the Labor Commission of the Communist Party USA. Art and George traveled together in Appalachia many times together.

In 1924, Art joined the staff of the Daily Worker. He was one of many Worker correspondents who chronicled the organizing of the mass production industries by the CIO during the 1930s. He interviewed United Mine Worker President John L. Lewis, Steelworker President Phil Murray and other top leaders of the CIO. He covered the founding convention of the CIO.

But his greatest admiration was for rank-and-file workers, some of them Communists, like coal miners Tom Myerscough and Pat Touhy, who saved the United Mineworkers in 1921 by organizing the miners who dug the coking coal for U.S. Steel’s mills in Western Pennsylvania; the intrepid Ben Carreathers, the African American organizer who outwitted the steel barons in signing up thousands of steelworkers under the noses of corporate security in Aliquippa, Pa.; and Paddy Whalen, the National Maritime Union organizer who led a maritime strike that idled Baltimore. (Whalen later died in the engine room of a ship torpedoed by the Nazis in World War II.) And his closest friend of all, George Meyers.

To die in Madrid

In 1939, Art arrived in Madrid to cover the last stand of the Spanish Republic. Art was arrested and thrown into a fascist dungeon. He barely escaped when he tricked his captors into taking him to the U.S. Embassy. Art broke free and lunged through the gate into the Embassy compound. Art reports that he staggered up the stairs of the Embassy. Who should he meet? Joseph Kennedy Jr., son of the U.S. Ambassador in London. Art was exhausted, but Kennedy wanted to talk politics. Why, he demanded, do Bolsheviks “believe in the inevitability of a bloody revolution, while the socialists do not?” Art answered that the fascists, not the Communists, instigated the bloodletting in Spain. Joe Kennedy, himself, died in the war. Art escaped from Spain and continued writing for another 44 years. He died in his 90s.

In Art Shield’s youth, a working-class upsurge rolled like a huge wave around the world. Art dove into that wave and swam with it, joyfully, the rest of his life.

Steelworkers Organization of Active Retirees (SOAR) leader George Edwards, a close friend of Art, told me, “Art not only swam with that wave, he influenced it. He not only reported on the struggles, he participated in them.”

Art was a proud member of the Communist Party USA. He loved the richly diverse membership: workers, men and women, of many races and nationalities. Art knew he owed those members: They distributed hundreds of thousands of the Worker featuring his stories at shop gates and in communities.

Keeping the faith

We continue to do that today with the People’s Weekly World. We work hard to carry on Art’s legacy. That pro-worker “bias” came home to me last night while watching Bill Moyers’ Journal on public television, a scathing exposé of the corporate media’s shameful support for George W. Bush’s war in Iraq. They peddled the lies, including Colin Powell’s mendacious speech to the United Nations. And what was our headline for the PWW distributed to the huge antiwar demonstration near the UN that frigid February day in 2003? “Powell at UN Caught in Web of Lies.” Art would have been proud!

In geologic time, we are still shaking off decades of Cold War retreat and “class partnership” nonsense. Yet a new wave, greater than ever, is gathering force. Labor is in the center of that new upsurge. Our goal in the 2008 elections must be a landslide victory, a new political realignment that ousts the Republican right. If Art were alive today, he would be swimming in the mainstream of that mighty new wave of workers’ struggles.

Tim Wheeler is the national political correspondent of the People’s Weekly World. The article is based on a speech delivered at the third Labor’s Voices conference in New York City.

Special thanks to Sandy Polishuk for inviting Tim Wheeler to participate in the Labor’s Voices panel. Polishuk is the author of “Sticking to the Union: An Oral History of the Life and Times of Julia Ruuttila.” Ruuttila exposed in the pages of the West Coast People’s World the racist, anti-working class response to the Vanport flood in September 1948, when the levees on the Columbia River broke and a town of 20,000 was inundated by a 20-foot wall of water. The survivors were treated similarly as the people of New Orleans and the Gulf Coast in the wake of Katrina.