A bestial and horrific spectacle is being planned in Arkansas. Unless it is stopped, eight death row inmates will be executed over a span of just 10 days in April. What’s the rush? The state’s supply of midazolam, the drug used in the executions, is expiring.

The bloodlust, inhumanity, and callousness are stomach turning. Especially given the torturous use of midazolam over the past few years that led to botched executions and prisoners writhing in excruciating pain as they gasped for breath and endured prolonged death.

The state of Mississippi is proposing to dispense with midazolam by bringing back the firing squad and gas chamber. Such thoughtfulness on the part of these elected officials.

The ghastly assembly line of slaughter operated by the state of Arkansas stands in stark contrast to the steep decline in actual use of the death penalty and changing public attitudes toward it.

“Thirty death sentences were handed down last year with 20 executions carried out – a 90 percent decline since the height in the 1990s when several hundred people were executed each year,” according to Julie Bourbon in the National Catholic Reporter.

Two percent of U.S. counties administer half of all executions. Only five states carried out executions in 2016: Georgia, Texas, Alabama, Missouri, and Florida.

It is impossible to make a case that the death penalty can be administered fairly. The entire criminal justice system is laden with racial and class biases, corruption, and ambitious politicians. If you are Black and poor, especially in the South, you are much more likely to get the death penalty.

As a recent New York Times investigation showed, receiving a death penalty sentence depends largely on one’s zip code and who the zealous prosecutor is.

“In June 2015, in the Supreme Court case Glossip v. Gross, which involved lethal injection, Justice Stephen Breyer noted in a dissent that only 15 counties – out of more than 3,000 across the United States – had imposed five or more new death sentences since 2010,” according to the Times.

Such flaws have been apparent for years. Convinced the death penalty violated the Constitution, Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun declared in 1994, “From this day forward, I no longer shall tinker with the machinery of death.”

Over the past few years the number of people exonerated on death row has grown exponentially. Presently, 157 death row inmates have been cleared of the crimes for which they were sentenced to die. This is an important factor in changing public opinion.

The task of raising public awareness of these cases falls largely on those whose lives have been directly impacted by them. One of those carrying the load is filmmaker Micki Dickoff.

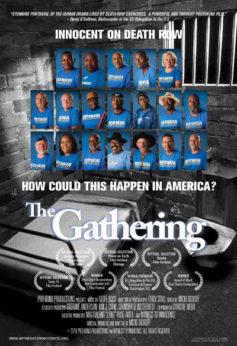

At the 2017 Peace on Earth Film Festival held in Chicago (March 10-12), Dickoff exhibited her powerful new short documentary The Gathering. The film tells the moving and disturbing stories of exonerated death row inmates and their families as they met together in Cleveland.

The film previously won best short documentary at the Fort Lauderdale International Film Festival. It’s not Dickoff’s first work concerning the death penalty; she also directed Step by Step: A Journey of Hope, another in a string of works highlighting the travails of those involved in struggles for justice.

She was also the writer and director of Neshoba: The Price of Freedom, a film that explores race relations forty years after the murder of Civil Rights martyrs Andrew Goodman, James Earl Chaney, and Michael Schwerner.

“For every 9 people on death row, one person gets exonerated. What about all the innocent people still on death row? And what about those who have been executed?” Dickoff asked.

Dickoff should know. Her first exposure to the death penalty was the case of a childhood friend Sonia Jacobs. Jacobs was on death row in Florida with her husband, Jesse Tafero, for killing two police officers.

Jacobs and Tafero maintained their innocence. After conducting her own investigation, Dickoff uncovered evidence that proved their innocence. After serving 17 years in prison, including 5 on death row, Jacobs was freed. But it came too late for Tafero, who had already been executed.

Dickoff largely self-financed The Gathering because she is so committed to ending the death penalty. “At my age it’s more important to get the word out,” she said.

Sharing the stage at the film festival with Dickoff was Nate Fields, Board Chair of Witness to Innocence, an organization of death row survivors, who was exonerated after spending 18 years in prison, including 12 years on Illinois’ death row. He was recently awarded $22 million in compensatory damages.

Also present was exonerated Paris Powell, who served 16 years in prison, including 12 on death row in Oklahoma, and executive director of Witness to Innocence and executive producer of The Gathering Megdaleno “Leno” Rose-Avila. Together with Sister Helen Prejean, “Leno” developed the effective strategy of imposing state moratoriums on executions.

As Arkansas races to kill people, the importance of the efforts of Dickoff and the organizers at Witness to Innocence becomes all the more apparent. As long as the expiration of human lives matters less than the expiration of drugs, how can we believe there is any possibility of real justice in our “criminal justice” system?