At the end of the 1970s, California farm workers were the highest-paid in the U.S., with the possible exception of Hawaii’s long-unionized sugar and pineapple workers. Today, people are trapped in jobs that pay the minimum wage and often less, and mostly unable to find permanent year-around work.

In 1979, the United Farm Workers negotiated a contract with Sun World, a large citrus and grape grower. The contract’s bottom wage rate was $5.25 per hour. At the time, the minimum wage was $2.90. If the same ratio existed today, with a state minimum of $10.50, farm workers would be earning the equivalent of $19.00 per hour.

But farm workers don’t make anywhere near $19.00 an hour. In 2008, demographer Rick Mines conducted a survey of 120,000 migrant farm workers in California from indigenous communities in Mexico—Mixtecos, Triquis, Purepechas, and others—counting the 45,000 children living with them, a total of 165,000 people. “One third of the workers earned above the minimum wage, one third reported earning exactly the minimum, and one third reported earning below the minimum,” he found.

In other words, growers were paying an illegal wage to tens of thousands of farm workers. The case log of California Rural Legal Assistance is an extensive history of battles to help workers reclaim illegal, and even unpaid, wages. Indigenous workers are the most recent immigrants in the state’s farm labor workforce, and the poorest, but the situation isn’t drastically different for others. The median income is $13,000 for an indigenous family, the median for most farm workers is about $19,000—more, but still far from a livable wage.

Low wages in the fields have brutal consequences. When the grape harvest starts in the eastern Coachella Valley, the parking lots of small markets in farm worker towns like Mecca are filled with workers sleeping in their cars. For Rafael Lopez, a farm worker from San Luis, Arizona, living in his van with his grandson, “the owners should provide a place to live since they depend on us to pick their crops. They should provide living quarters, at least something more comfortable than this.”

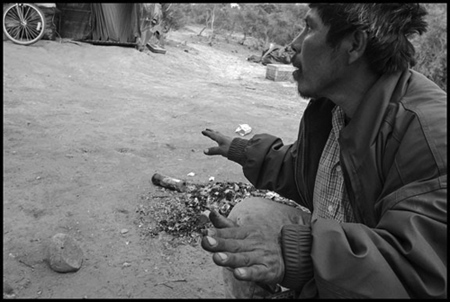

In northern San Diego County, many strawberry pickers sleep out of doors on hillsides and in ravines. Each year, the county sheriff clears out some of their encampments, but by next season workers have found others. As Romulo Muñoz Vasquez, living on a San Diego hillside, explains: “There isn’t enough money to pay rent, food, transportation and still have money left to send to Mexico. I figured any spot under a tree would do.”

Compounding the problem of low wages is the lack of work during the winter months. Workers have to save what they can while they have a job, to tide them over. In the strawberry towns of the Salinas Valley, the normal 10 percent unemployment rate doubles after the harvest ends in November. While some can collect unemployment, the estimated 53 percent who have no legal immigration status are barred from receiving benefits.

Yet people have strong community ties because of shared culture and language. Farm workers in California speak twenty-three languages, come from thirteen different Mexican states, and have rich cultures of music, dance, and food that bind their communities together. Migrant indigenous farmworkers participate in immigrant rights marches and organize unions.

Indigenous migrants have created communities all along the northern road from Mexico to the U.S. and Canada. Migration is a complex economic and social process in which whole communities participate. It creates communities which today pose challenging questions about the nature of citizenship in a globalized world. The function of these photographs, therefore, is to help break the mold that keeps us from seeing this reality.

The right to travel to seek work is a matter of survival for millions of people, and a new generation of photographers today documents the migrant-rights movements in both Mexico and the United States (with its parallels to the civil rights movement of past generations). Like many others in this movement, I use the combination of photographs and oral histories to connect words and voices to images—together they help capture a complex social reality as well as people’s ideas for changing it.

Today racism is alive and well, and economic inequality is greater now than it has been for half a century. People are fighting for their survival. And it’s happening here, not just in safely distant countries half a world away. As a union organizer, I helped people fight for their rights as immigrants and workers. I’m still doing that as a journalist and photographer. I believe documentary photographers stand on the side of social justice—we should be involved in the world and unafraid to try to change it.

“I’m going to be a rapper with a conscience.” – Raymundo Guzman

I was very young when my mother first took me to work in the fields—about eight or ten years old. At first only she and my older brother were working. My brother would work with her, while the rest of us went to school. She took me to the fields so that I could start to learn, so that I would be ready when I was old enough to work.

It was just her and us kids, and she couldn’t earn enough to support us all. She sold tamales and chicharrones, and tried to make money any way she could. In December, she pruned trees. She was our mother and father. She had to look out for us. When there wasn’t work in the fields she would kill a pig and make tamales, make mole, and sew.

My memories of those times are good because I was working with my family and the people from my hometown. We all came from the same town in Oaxaca, San Miguel Cuevas. When I first arrived in Fresno I only spoke Mixteco. I had to learn Spanish to speak with other people in the street and in school.

I graduated from high school. I was the first in my family to do it. My mother was so proud that she threw me a party. It felt good to stand on stage and hear my name being called. I felt sad immediately afterwards, though, because I didn’t know what to do with my diploma. It’s like accomplishing something so big, and then everything comes crashing down. It’s very depressing.

I was already working in the fields then, so I actually lost a day of work for graduation practice. I went to work in Oregon right after graduating, because I was saving up for a car. But the money seems to slip away. It’s not much to begin with. The money you earn in a week goes to rent, food, gas, and the cell phone bill.

I’m going to be a rap star. I think I’m going to be big, but I’m going to be a rapper with a conscience. My idol is Tupac Shakur. He spoke about politics and told the truth about all of us kids in poverty. He talked about our lives. It’s like Tupac used to say, we’re a flower that grew in concrete. You can see the rose and stem is twisted, but it grew out of the hard concrete. We’re from the hood but we’re going to come up. Some people may not want us to achieve much, but we’re human too.

“Here on the hillside.” – Rómulo Muñoz Vazquez

In San Pedro Muzuputla, the town I’m from, we’re very poor, and I have four children. This is my second time coming to the United States, and I’ve been living in this encampment in San Diego for a year. When I first arrived, I rented an apartment, but I couldn’t make enough money to pay rent, food, transportation, and still have money left to send to Mexico. I figured any spot under a tree would do, so I asked a coworker and he told me about this place. I bought some nylon and a tarp for the roof, and built my shack myself. My main goal is to save money and send it to my family.

We’re outsiders. If we were natives here, then we’d probably have a home to live in. But we don’t make enough to pay rent. We’re poor and can’t afford to go elsewhere.

Here in the camp very few speak Spanish. Most just speak their indigenous language. Those from Guerrero speak one language; the people from San Pedro Muzuputla speak another. We speak Amuzceñas. We don’t understand Mixteco or Triqui—it’s very different. That’s why it’s good to speak Spanish.

When we aren’t working, we’re looking for work. Sometimes Americans stop by, and even though we only communicate by hand signals, they can tell us what job they want done. I was beaten at work five years ago, on a ranch by the freeway in San Diego. The boss asked us why we weren’t working hard. I told him we weren’t animals and we had rights. I still remember everything they did to me afterwards.

David Bacon’s photographs and stories seek to capture the courage of people struggling for social and economic justice in the Philippines, Mexico, and the United States. The text and photos are excerpted from his 2017 book, “In the Fields of the North / En Los Campos del Norte,” published simultaneously by the University of California Press in the U.S. and El Colegio de la Frontera Norte in Mexico.

In the Fields of the North / En los Campos del Norte

Photographs and text by David Bacon

University of California Press / Colegio de la Frontera Norte

302 photographs, 450pp.

Paperback, $34.95

Order the book on the UC Press website. Use source code 16M4197 at checkout to receive a 30 percent discount.

En Mexico, se puede pedir el libro en el sitio de COLEF.