“If you are silent about your pain, they’ll kill you and say you enjoyed it.”—Zora Neale Hurston

Novelist, folklorist, and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston was a leading voice in the Harlem Renaissance. A social, intellectual, and cultural explosion taking place from the 1910s to the 1930s, centered in Harlem, New York City, the “New Negro Movement,” as it was known at the time, helped move forward both politics and art in the framework of the Black experience, which still influences us today.

Hurston was among other trailblazers like herself who dared to define and explore Black life through various art forms. Often times these expressions of art were a means to celebrate what it meant to be Black in the United States. The art of the Harlem Renaissance could be seen as a means of resistance to the status quo of Black Americans as second-class citizens. Hurston, through her work, sought to change the oppressive narrative of Black people as told from the perspective of white supremacy, and allow it to be told by Black people themselves.

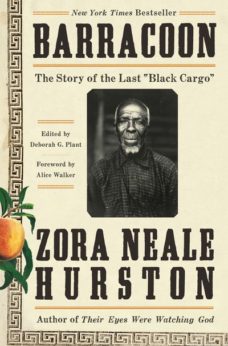

Hurston’s book Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo”, which explores the tragedy of slavery through the words of one of the last surviving victims of the African slave trade, exemplifies such a goal. It is being published over sixty years after her death, but it’s a timely work now more than ever. For its very existence, in its original form, is an act of resistance. It is an unapologetic look at U.S. history, Black pain, and the ramifications of the slave trade on a people, told in their own voice.

Hurston’s book Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo”, which explores the tragedy of slavery through the words of one of the last surviving victims of the African slave trade, exemplifies such a goal. It is being published over sixty years after her death, but it’s a timely work now more than ever. For its very existence, in its original form, is an act of resistance. It is an unapologetic look at U.S. history, Black pain, and the ramifications of the slave trade on a people, told in their own voice.

Barracoon is an interview with one of the last known survivors of the Atlantic slave trade. Cudjo Lewis (Oluale Kossula), 87 at the time of his interviews with Hurston, gives a first-hand account of his journey from being abducted from Africa on one of the last “Black Cargo” ships, and transported to the United States. The work reflects the three months that Hurston spent with Lewis in his African-centric community, called Africatown, some miles outside of Mobile, Alabama. Hurston gave Lewis a platform to tell his story, to put a human face to the tragedy and brutality of slavery, and the lasting effects on the people who endured it. Hurston also allowed Lewis to tell his story in his authentic voice and dialect.

The book was initially rejected in 1931 by Viking Press. Viking Press wanted Hurston to rewrite the interview so that it didn’t have as much “black dialect.” Hurston refused to do this. She saw the importance of Lewis being able to be read and heard in his own vernacular after being stolen from his home country and placed in a land that only saw him as a means of labor and capital.

Deborah Plant, who edited Barracoon, explained the reasoning for Hurston’s refusal to make the changes that Viking Press requested. “We’re talking about a language that he had to fashion for himself in order to negotiate this new terrain he found himself in,” Plant explained. “Embedded in his language is everything of his history. To deny him his language is to deny his history, to deny his experience—which ultimately is to deny him, period. To deny what happened to him.”

Hurston’s refusal to make the changes resulted in Barracoon never seeing the light of day outside of the Howard University library for 87 years. Amistad at Harper Collins has worked to release Hurston’s work for the public this month. Plant explains, in the introduction of the book, that there exist only eight accounts that chronicle or even mention the Middle Passage, written by Black people. Hurston’s work is now one among the too few. It will also be the only account compiled by a Black woman.

Barracoon will join Hurston’s other works such as Mules and Men (1935), Jonah’s Gourd Vine (1934), Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), and Moses, Man of the Mountain (1939) that tell the story of Black people in a unique and authentic way. Although Hurston is recognized today as a literary icon, she died in near poverty, not being allowed to enjoy the kind of attention her work should have garnered. With Barracoon, a new generation will be allowed to witness for the first time Hurston’s unique contribution to history and knowledge. It is a timely example of the need for the oppressed to tell their story in their own words, and the power within those words. As Hurston wrote in the book:

“All these words from the seller, but not one word from the sold. The Kings and Captains whose words moved ships. But not one word from the cargo.”

The “cargo” gets to tell their story, one that will challenge the often watered-down narrative of slavery, told by those whom the larger society might rather forget. Hurston’s work dares the reader to listen and to learn. She worked to give voice to the voiceless, and that legacy will continue to live on today.

Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” by Zora Neale Hurston.

Deborah G. Plant: Introduction, Alice Walker: Foreword.

Available in Hardcover, paperback, Kindle, and Audiobook editions.