British royalty in 1947 staged the lavish marriage of Princess Elizabeth to the scion of a wealthy, titled German family, Philip Mountbatten, Duke of Edinburgh. The press devoted millions of words, entire pages, and front-page headlines to this event, just as is happening again this weekend for the marriage of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle. On the day after the 1947 wedding, our predecessor, the Daily Worker, under large headlines, ran the following page one story about working-class couples in New York who just happened to share a wedding day with the royals. For details on Elizabeth and Philip’s nuptials, readers were asked to turn to page three.

18 couples wed quietly at City Hall, non-royal lovers united in simple rites

by Bernard Burton

November 21, 1947

Eighteen non-royal couples were wed quietly yesterday at the City Clerk’s office in New York City’s Municipal Building. An on-the-scene check revealed that the brides and grooms had come from such widely scattered points as the East Bronx, Flushing, Harlem, Yorkville, Chelsea, Bedford-Stuyvesant, Williamsburg, Flatbush, Bensonhurst, and East New York.

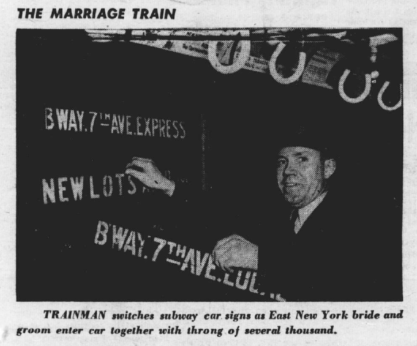

The couple from East New York, both of them young and slightly awed, repeated the itinerary of their wedding procession as they waited in the anteroom, waiting for “next.” The bride, attired in a pale blue, flowered print dress, purchased a week earlier at a prominent 14th Street store, had left her mother’s three-room apartment, Van Siclen and Livonia Aves., at 9:30 a.m. to meet the groom at the I.R.T.’s New Lots Ave. Station.

The bride wasn’t accompanied by her father, who had left several hours earlier for Manhattan to attend to his duties as a clothes presser in a building at West 37th St. The prospective mother-in-law was also unable to participate in the procession, being compelled to attend to her three-year-old grandson, whose working parents reside in the same three-room apartment.

Walking with a buoyancy which ignored the dull, chill morning, the bride hurried her steps as she spied the groom waiting at the foot of the stairs to the El. They greeted each other with a graceful embrace and a kiss which left hardly a smudge of Prince Feather Lipstick on the groom’s smiling lips.

The groom was also unescorted. He wore a gray suit, a topcoat, and the cool breeze ruffled his light brown hair. He was hatless.

The bride, who had ash blond hair, straightened her navy-blue hat, which was trimmed with a wisp of veil, as the couple, holding hands, slowly climbed the steps. They were temporarily parted as the waiting crowd on the platform thronged abruptly into the same car.

The separation, however, lasted only to Utica Avenue, where they transferred for the Lexington Avenue Subway. This time, they vowed, there would be no separation. With the bride holding grimly to his waist, the groom, who stands five, ten inches, and weighs about 182 pounds, charged through the crowd. There was no seat for the non-royal couple. Nevertheless, the 20-minute ride to Brooklyn Bridge held its recompense. The couple stood close together, swaying in rhythm with the train, with the bride’s veil occasionally tickling the groom’s nose.

At Brooklyn Bridge, they were hastily ejected from the car, but they again slowly mounted the steps, and made their way across the square which was crowded with cars honking their horns. Traffic police showed visible sign of losing their patience as they tried to keep the traffic moving.

As they reached the hallway to the City Clerk’s office, they were unceremoniously ushered into the anteroom by other brides and grooms seeking to be first in line. One couple thought that they were about fifth.

The groom, who wore a ruptured duck [a slang term for The Honorable Service Lapel Button worn by World War II veterans] on his lapel, arose suddenly as a clerk called two names. “That’s us, honey,” he said, and they walked into the office with two witnesses, who had met them in the anteroom. They were shopmates of the groom, who holds the post of polisher in a Brooklyn metal plant.

In the clerk’s office, a little tired man droned through the ceremony, waited for the “I do’s,” and declared, “I now pronounce you man and wife.”

They returned to the apartment of the bride’s family where her mother greeted the newlywed with: “The folding bed came from the store. We’ll put it up in the kitchen tonight.”

There were no gifts from the White House.

(The article also appeared in the book, Fighting Words: Selections from Twenty-five Years of The Daily Worker, New Century Publishers, New York, 1949.)