SEQUIM, Wash.—I regret that I did not meet Harold Wade Jr., who entered Amherst College as a freshman in 1964, the same year I graduated from that institution. He was one of a handful of African Americans admitted to Amherst, then an all-male liberal arts college. Wade died tragically in a drowning accident in the Bahamas in 1974. Two years later, through the determination of his mother, Thelma Wade, Amherst College Press published a book, Black Men of Amherst, which Harold Wade Jr. wrote before he died.

I am grateful to Kathleen Whittemore who wrote a cover story for the Winter-Spring 2018 edition of Amherst, dedicated to Harold Wade Jr. Her story, headlined “His Black History: The Unfinished Story of Harold Wade Jr. ’68,” brings my classmate alive for me. Harold Wade graduated with honors from Amherst and went on to Harvard Law School. After he graduated, Wade moved back to New York City, where he got a job as an assistant to Deputy Mayor Paul Gibson.

But Whittemore is silent on one point: Did Wade make mention of Benjamin J. Davis Jr., who graduated from Amherst in 1925? I devoted a chapter in my book, News From Rain Shadow Country to Davis’s visit to his alma mater at the invitation of Prof. Tom Yost. I heard Davis speak and went to Yost’s home afterward, where I met and spoke at length with Davis about his eventful life as an African-American Communist.

Finally, I found a copy of Wade’s book online for $12.64. It arrived, a hardcopy in perfect condition. It is stamped “Withdrawn” from the University of the Pacific library in Stockton, California.

When I opened the slim book, I found many pages devoted to Benjamin J. Davis, Jr. Wade recounts in detail Davis’ services as an Atlanta attorney for Angelo Herndon, a Black youth, framed on “insurrection” charges for daring to organize a multiracial march of the unemployed in 1932. Convicted by an all-white jury, Herndon faced the death penalty. Ben Davis vowed to appeal the case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Wade writes, “After the Herndon trial, liberal blacks and whites formed a coalition to defend Angelo Herndon—in much the same way as similar groups rally to ‘Free Huey’ or ‘Free Angela.’” The Supreme Court threw out Herndon’s conviction in a 5-4 decision. In the middle of the legal fight, Wade reports, Davis joined the Communist Party USA.

Wade quotes a 1947 article by Ben Davis entitled “Why I am a Communist.” He also quotes Angela Davis’ interview in Ebony magazine on why she too joined the Communist Party. Racist oppression is central to the system of capitalist exploitation, both argue. The Communist Party USA has played a spearhead role in the struggle against racism and for the unity of African-American and white people throughout its history. “Black, Brown, and White Unite. Same Class, Same Fight,” has long been one of the party’s main slogans. And like the CPUSA, both Ben and Angela Davis argue that socialism is central to winning full equality.

Ben Davis moved to New York where he became a Daily Worker reporter assigned to Harlem. In 1941, Adam Clayton Powell, then a member of the New York City Council, announced he would not seek re-election because he was running for a seat in the U.S. Congress. Ben Davis announced he was a candidate to fill the City Council vacancy. Wade reports that Davis won under New York’s progressive system of “proportional representation.”

Writes Wade, “Benjamin Davis has the distinction of being the highest elected avowed Communist in the history of the United States…and in 1943 he was the only elected black in New York City government. Throughout the 1940s, he and Powell were the most dynamic politicians in black politics in America.”

Ben Davis, Wade adds, “was so popular that in 1945 he ran virtually unopposed.” Together with fellow Communist Pete Cacchione of Brooklyn, Davis “became responsible for the passage of rent control regulations in New York City.”

Cold War witch-hunters targeted Ben Davis and other top leaders of the Communist Party, Wade continues.

“The Red Baiting Era of Joe McCarthy had begun…. Judge Medina sentenced Davis to five years and a $10,000 fine. Davis became the first person expelled from the New York City Council…. While serving time in the Federal Penitentiary at Terre Haute, Indiana, Davis filed a case to desegregate federal prisons.”

After his release from prison in 1955, Davis returned to the Daily Worker. In 1959, he was elected National Secretary of the CPUSA.

“In 1960 Davis visited Amherst at the invitation of undergraduates to speak about the Communist Party and related topics,” writes Wade. “Observers report that Davis recalled fond memories of his student days at Amherst, despite the fact that, as an outstanding violinist, he was denied admission to the orchestra.”

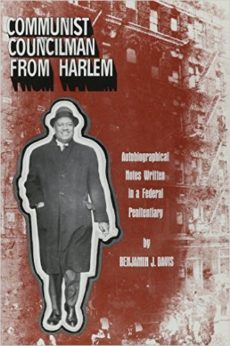

Wade writes that “Ben Davis’s autobiographical notes were released from prison one year after his death and ten years after his release from prison. Since they were not published until 1969, his story is just being re-told.” Wade is referring to Communist Councilman From Harlem published by International Publishers in 1969.

Wade reports that Amherst became a college of the wealthy elite in the 1890s. During those years, he adds, an estimated 1,700 Negroes were lynched in America. “This period of capital accumulation was precisely the period in which blacks were being deprived of all their rights,” he writes.

He dwells on one of the most dramatic incidents in African-American history: Dr. W.E.B. DuBois’ debate with Booker T. Washington in which DuBois debunked Washington’s line that African Americans should strive only to be skilled tradesmen, not seek higher education at places like Harvard.

Harold Wade Jr. makes no secret which side he is on: Dr. DuBois all the way. Wade’s book helped push open the doors of places like Amherst for African-American applicants. And women too, since during these same years, Amherst decided to become a co-educational school.

Whittemore reports that Frost Library may republish Black Men of Amherst. I hope so. The book reads as fresh, clear, and strongly argued as the day Harold Wade Jr. wrote it.