Women make up almost one-third of all agricultural laborers, but the presidents and most top leaders of the United Farm Workers have invariably been men. Dolores Huerta, the union’s fiery co-founder, faced down growers and negotiated many of the union’s contracts. She became secretary-treasurer, but not president.

Does it make a difference? The UFW has chosen a new president, Teresa Romero, who says it does. Although she’s never worked in the fields, she believes her gender gives her a close connection to the lives of the women who do.

After her election by the union’s executive board on August 28 (the next convention in 2020 will make a permanent choice), Romero’s first field visit was to lettuce and broccoli harvesters working in Salinas for the D’Arrigo Brothers Company. “In some crews a majority of the workers are women,” she says. “There was a time when they didn’t hire women for some jobs. I don’t know what the reason was, but whatever it was, it was wrong.

“Women can do everything, and we want the opportunity to do it. I’ve seen some older women in their 50s doing work that some younger people can’t. If growers are worried about a labor shortage, there are women out there who can do the work. But they want to be paid equally, and treated respectfully.”

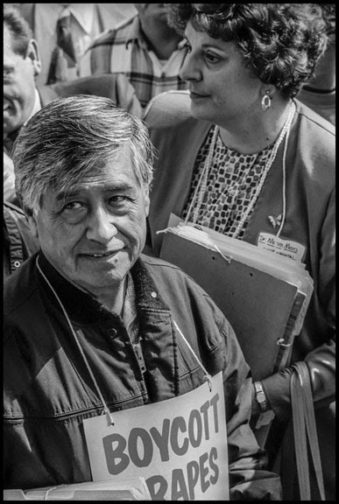

After 25 years as president of the United Farm Workers, Arturo Rodriguez is retiring in December, and the union has selected an immigrant woman to replace him. The UFW has had only two presidents in 50 years: Before Rodriguez, it was Cesar Chavez.

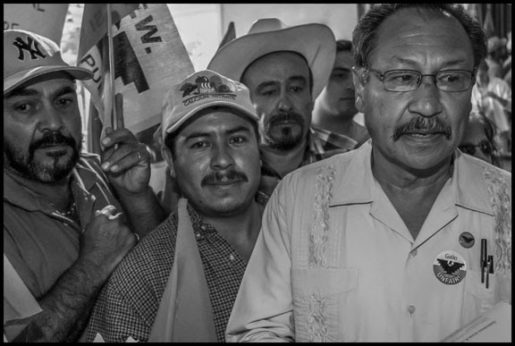

This is more than a changing of the guard. Internally the union is trying to reflect more accurately its members. And while acknowledging the epic battles of its early years, it is coming to terms with a new group of California growers, some of whom see an advantage in cooperation, even though others still want a fight to the death.

The UFW is also looking for ways to address more directly the problems of its women members. Women in the fields are especially vulnerable in today’s anti-immigrant political climate, Romero charges. “Harassment is very difficult for women to talk about, especially when they feel they might be deported and separated from their children. And for women, being fired is not their problem alone. Most are working with their husband or brother or sister, and abusers hold those jobs over their heads. It’s important to have women in charge of crews as supervisors, to make it easier for a woman to come and say, ‘This is what happened to me.'”

More than 90 percent of California farm workers were born in Mexico, yet UFW presidents until now have come from families with roots on the U.S. side. Chavez was born north of the border, in Yuma, Arizona, in 1927. Rodriguez, who followed Chavez in 1993, hails from San Antonio, Texas. Larry Itliong, the Filipino labor leader who shared leadership with Chavez during the union’s initial five-year grape strike, was an immigrant, born in Pangasinan, in the Philippines. But he was never president.

Born in Mexico City, Romero grew up in Guadalajara and came to the U.S. in her 20s. She worked, successively, in a shoe store, in a lawyer’s office, as assistant to Rodriguez, and finally as UFW secretary-treasurer. While she doesn’t speak Zapoteco, the language of her grandmother, her roots as an immigrant with indigenous ancestry match the changing demographics of California’s field laborers. People from southern Mexico, speaking Mixteco, Purepecha, and Triqui as well as Zapoteco, are the fastest-growing group among farm workers. They’ve often been the backbone of UFW organizing campaigns and strikes during the last several years.

“I did what my grandmother did when she left Oaxaca to come to Mexico City,” Romero says. “Like her, I moved to a different place where I didn’t know the language or the culture. I never thought it would be forever, yet now I’ve been here over 30 years. That’s what happens in the fields too. The workers and I share that same immigrant experience.”

The UFW was slow to adjust to the rise in indigenous migration. In the early 1990s, it signed an experimental agreement with an organization of Oaxacan migrants, the Binational Front of Indigenous Organizations. Rodriguez credits its former coordinator and Mixteco leader, UCLA professor Gaspar Rivera, with helping the union understand their culture. Indigenous organizers were slowly hired. In the early 2000s, the UFW became a vocal defender of Triqui-speaking workers in the Salinas Valley community of Greenfield, organizing marches when immigration raids targeted them.

Union meetings are still mostly in Spanish, as are contracts (which are also in English), but translation into indigenous languages is becoming more common. “It has been a challenge,” Romero says. “But if we don’t understand people’s culture, they will see us as outsiders. When we learn and understand what’s important to them, it opens doors.”

The United Farm Workers is not the same union Cesar Chavez left in 1993 when he died in San Luis, Arizona. He’d gone to Yuma, just a few miles from his birthplace, to testify in an all-consuming legal case against one of the union’s most bitter enemies, the Bruce Church lettuce company. Bruce Church, like many other growers whose workers had voted for the union in the late 1970s, refused to negotiate with the union.

By the time Chavez died, the UFW had shrunk to a few thousand members from a peak of about 40,000 in the late 1970s. Over 160,000 workers had voted for the union under California’s Agricultural Labor Relations Act, the law the union had fought for in 1975. Like Bruce Church, however, most growers wouldn’t sign contracts. Many others who did either went out of business, changed their names and dumped their workers, or simply refused to renew their agreements.

Wages fell. “Things got so bad that the year before Cesar died we wanted to do something to give people hope,” Rodriguez remembers, “and thousands of workers went on strike in Coachella to raise wages.” Two years later the union repeated its seminal march of 1968, from Delano to Sacramento. “Cesar was gone. But that didn’t mean we wouldn’t continue to fight.”

In 1996 Bruce Church finally did sign a contract to settle its decades-long legal war with the union, and over the next 25 years, the UFW stabilized and began to grow. According to Rodriguez, 10,000 people now work under union agreements, mostly in California.

A successful boycott at the Chateau Saint Michelle winery in Washington state gave organizers the idea for an arrangement to force growers to negotiate. “The workers there won a contract using the idea of mandatory mediation,” he says. The threat to return to the boycott was so powerful that the company agreed that a contract would be imposed if negotiations hadn’t concluded by a set date.

In California, the union convinced the legislature to pass a law with the same mechanism, to deal with the many companies where workers had voted for the union, but which never signed contracts. Now, if a grower won’t negotiate after its workers organize and vote for the union, a state mediator can write up an agreement and the Agricultural Labor Relations Board can impose it.

Growers predictably challenged the law, but the California Supreme Court upheld it in 2008. Several large growers, employing thousands of workers, then signed contracts, either because the state imposed them, or knowing that the state would if they didn’t agree. That inspired further challenges. The world’s largest peach grower, the Gerawan family in Fresno, tried again to have the law declared unconstitutional, but again the state courts upheld it. That case is now on appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

“Mandatory mediation is important to us,” Romero says. “If workers vote for a union, we have something we can use to get an agreement. But a law on the books doesn’t by itself create change in the fields.”

The union also persuaded the legislature to act on issues affecting workers far beyond its own members. Until recently, at least one worker died in the fields every year, in the fierce summer heat in the San Joaquin Valley where temperatures routinely exceed 100 degrees. When a pregnant young woman, Maria Isabel Vasquez Jimenez, collapsed in 2008, the uproar over her death inspired protective legislation. “I went to so many funerals of people who died of the heat,” Rodriguez recalls. “Her death stuck with me, though, in part because her father Doroteo lost his job when he spoke out. We won today’s heat protections because of what they and others lost.”

Another legislative victory gained overtime pay for farm workers on the same basis as other workers. “We convinced legislators when we reminded them that farm workers had been excluded from overtime by racism long ago,” Romero says.

Overtime pay and heat protection have now been extended to all farm workers in California. Yet, taking inflation into account, farm workers are paid much less today than they were in the period of the union’s greatest strength in the late 1970s. The master vegetable contract of that era pegged starting hourly pay at about 2.5 times the minimum wage. If the same ratio held today, California farm workers would be earning over $27 an hour. Instead, wages are close to the minimum of $11 an hour for large employers this year, and $12 next year. It’s not uncommon to find groups of migrant workers living under trees, or sleeping in their cars at harvest time.

While union contract wages are generally much higher than the minimum wage, the UFW faces a daunting challenge in trying to raise the income of farmworkers across the board. Meanwhile, the contested terrain between growers and the union is changing rapidly. For several decades corporate growers have been globalizing their operations, growing fruit and vegetables in many countries. At the same time, as trade agreements like NAFTA have displaced poor rural communities in Oaxaca and elsewhere, farmers have come to the U.S. looking for work and survival. “We have a mostly undocumented workforce, and no immigration reform in sight,” Rodriguez says. “Growers are running away to Mexico and elsewhere. It’s a huge problem.”

Even as immigration enforcement is creating a climate of fear in California farm-worker towns, the government is encouraging growers to hire that flow of displaced people, but only as temporary contract labor through the H-2A visa program. President Donald Trump, despite his otherwise sour anti-immigrant rhetoric, told a rural Michigan rally in February, “We have to have strong borders, but we have to let your workers in. We have to have them.”

In the last few years, the number of workers brought to California on temporary H-2A work visas has climbed steeply. The state’s growers imported 3,089 H-2A workers in 2012. In 2017 the number had mushroomed to 15,232-a 500 percent increase in just five years. Some growers see the possibility of replacing at least part of their workforce of resident farm workers with this contracted labor. Some major agricultural corporations, among them Tanimura and Antle, are building barracks for hundreds of H2-A workers in Salinas.

Some immigrant rights activists have called for abolishing guest worker programs, citing the abuse of the workers, and the potential for undermining the existing farm labor workforce. Romero and Rodriguez believe growers face a labor shortage, however, and need at least some H-2A workers at peak harvest times.

Romero argues that if there are going to be H-2A workers, the union has to protect them like other workers. “In Mexico, they are charged thousands of dollars by recruiters, which is illegal. The [recruiters] bring them here and take away their documents. Some families in Mexico haven’t heard from their loved ones for months, or don’t even know if they’re alive. And the contractors say ‘no women.'” The union helped set up an organization, CIERTO, which advertises “clean recruitment.” It also partners with organizations in Mexico that monitor the recruiters.

But the H-2A program, with its threat to replace the established workforce, scares the workers living here, Romero admits. As well, defending the rights of H-2A workers is extremely difficult, as growers can fire them for protesting abuse or not working fast enough, which then triggers the workers’ deportation. But Romero remains optimistic that growers will never be able to use the program to replace their workforce.

As she sees it, the future of the UFW lies in its ability to work with growers like D’Arrigo Brothers. The union just renegotiated a contract with the company covering 1500 resident farm workers, along with about 200 H-2A visa holders. Some D’Arrigo employees have worked at the company for several decades. John D’Arrigo says that the key to dealing with the current shortage of farm labor is to encourage workers to stay by making them direct employees, rather than hiring them through contractors.

“With direct hires, there’s less product left in the field,” Romero says, outlining a potential increase in productivity. “D’Arrigo wants the workers to come back year after year-a workforce that is part of the community. If he gives them benefits, they’ll want to keep coming back. We can have a training program, with older workers spending time with newer ones. The company can listen more to the workers, to see what works and what doesn’t, making workers part of the solution-not just pushing them to work faster.” Items like the training program remain options for future contracts, but the new agreement does provide family health care, with the company paying the premiums, along with increased job security.

Cooperation, Romero believes, helps both management and labor. “When we work together workers bring solutions to the table. Production is better. Quality is better.”

Part of her argument is that farm labor is undervalued, not just economically, but socially. “Growers need a competent and stable workforce,” she emphasizes. “Nobody knows what’s happening at the farm level better than the workers. The people are skilled and experienced. They have endurance. Farm work is a profession that deserves the same respect and consideration as a reporter or an engineer.”

Cooperation, however, hasn’t often been the norm in agricultural labor relations. According to Rodriguez, “We have to change what attracts workers to agriculture. There have to be better wages, but that’s not everything. The work can’t require that someone be disabled by their job by the time they’re 50 years old.”

The UFW, however, was born in massive strikes and national boycotts, which forced giant grape growers like John Giumarra and Richard Bagdasarian to sign contracts in 1970. Those companies are still a big presence in California agriculture, and not at all friendly to the union.

If the union has to fight, the boycott is still an effective weapon, Rodriguez says. “You don’t need to cut 50 percent of their business. A small group of committed people can influence consumers and have an impact. If there’s no other way, then that’s necessary.”

Romero agrees, although she’d clearly prefer talking to fighting. “People like Giumarra-I don’t know if we’ll ever change them,” she says. “Those who want to do things the old way have to be forced to change conditions. If workers say a company isn’t doing right, and they want to strike and boycott, then we’re going to do it.”