Every year on October 2 thousands of Mexican students pour into the streets of Mexico City, marching from Tlatelolco (the Plaza of Three Cultures) through the historic city center downtown, to the main plaza, the Zócalo. They’re remembering the hundreds of students who were gunned down by their own government in 1968, an event that shaped the lives of almost every politically aware young person in Mexico during that time.

This year, just days before the march, the municipal police in Iguala, Guerrero, shot students from the local teachers’ training college at Ayotzinapa. More demonstrations and marches are taking place all over Mexico, demanding that the government find 43 students still missing. Students marching on October 2 were in the streets for them as well, aware that the bloody events of 1968 were not so far away in some distant past.

Raúl Álvarez Garín was one of those whose world changed at Tlatelolco. He was a leader of the national student strike committee, organizing campus walkouts and street mobilizations through the spring of 1968. This rebellious upsurge was simultaneous with student protests in France, the United States and, it seemed then, the whole world. In Mexico, it culminated in a huge rally at Three Cultures Plaza.

The Mexican government was preparing for the Mexico City Olympics that year. It had never tolerated political dissent beyond very narrow limits, but then it was even more defensive than usual, fearing any social movement that appeared to challenge its hold on the country’s politics. The authorities decided to bring out the army and shoot the students down.

Somehow Álvarez survived the bullets in the plaza and was then shut into a cell in the notorious Lecumberri prison for two years and eight months. He died two weeks ago on September 27, having spent a lifetime trying to assign responsibility for the decision to fire on the crowd. There was actually no mystery about it. The orders for the massacre were given by then-Secretary of the Interior (Gobernación) Luis Echevarria. But Echevarria was acting for Mexico’s political establishment, organized in the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). Álvarez wanted the crime acknowledged publicly and the guilty punished. By spending the next half-century pursuing that goal, he became not just a hero to the Mexican left, but its conscience.

Álvarez was already a man of the left when he got to Tlatelolco. He’d joined the Young Communists but then left before 1968. He married María Fernanda Campa, daughter of Valentín Campa, one of Mexico’s most famous radicals who lived underground and went to prison after leading a railroad workers strike in 1958. After his release, Campa became the 1976 presidential candidate of the Mexican Communist Party, before it merged with other parties and eventually disappeared.

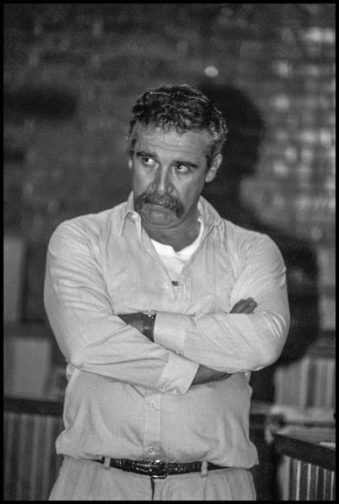

Later in life, it was hard to imagine Álvarez as he was described by friends in ’68–a skinny intense youth of 27. When I met him in 1989 he was already a man of substantial girth. We’d go to lunch with his brother, economist Alejandro Álvarez, and spend hours talking politics. Raúl would get animated, talking beneath his huge mustache faster than my broken Spanish could keep up. He’d ask a hundred questions about Mexicans and unions in the U.S., and we’d plan articles for the newspaper he edited, Corre la Voz (Spread the Word).

Álvarez believed that words have power. Long before Corre la Voz, he started another famous Mexican leftwing journal, Punto Crítico, with other 1968 veterans. His goal was to make his politics accessible to ordinary people, not to inspire debate among dogmatists. “He put our debates into context and showed their limits,” remembered Luis Navarro, now an editor at Mexico’s left-wing daily La Jornada. “His language was always understandable.”

Through the years after 1968 he supported every worker’s fight that seemed capable of improving conditions, but that also challenged the political order. As Mexico’s political structure began to change in the 1980s, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas ran for President in 1988 against the PRI his father had founded 40 years earlier. Álvarez and others saw the Cardenas campaign as an opening to wrest power from the PRI, 20 years after Tlatelolco. As the votes for Cárdenas were being counted, and it was clear he was winning, the election computers suddenly went down. When they came back up the next morning the PRI candidate, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, one of the country’s most corrupt politicians, was declared the winner.

During and after that campaign, many currents of the Mexican left came together and organized the Democratic Revolutionary Party. Álvarez was a founder. He began to look for a way to break workers and unions free of the PRI, to give the new party a working-class base. I met him that year after the election when I came to Mexico with other U.S. trade unionists. The North American Free Trade Agreement was already on the horizon. Raúl and Alejandro Álvarez were some of the first people who saw the advantage of cooperation in trying to fight it on both sides of the border.

I was beginning to work as journalist north of the border. Raúl and Alejandro helped me understand that for all of NAFTA’s disastrous impact on the workers of my country, the trade agreement would have much worse consequences in Mexico. I spent last week as a judge in the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal investigating the causes of migration from Mexico to the United States and the terrible violations of the rights of migrants in both countries. It’s clear that if anything, they underestimated the damage. And repression in Mexico is not just a thing of the past. As we met as judges in the Permanent People’s Tribunal, just days after Raúl Álvarez died, we heard testimony about yet other mass killings–of 73 migrants killed and buried in the desert in northern Mexico, and the discovery of 193 more in 47 graves less than a year later.

The PRI finally lost the Presidency in 2000, although not to the left but to the rightwing National Action Party. Nevertheless, Álvarez believed it might be possible to get a new government, even a conservative one, to call the murderers of 1968 to account. A new office was created, the Special Prosecutor for Social and Political Movements of the Past. Álvarez, Felix Hernández Gamundi and Jesus Martin del Campo filed a legal case against Echevarria over the Tlatelolco massacre, the killings of other students in a street protest in 1971, and the “dirty war” in which the Mexican government targeted leftists for assassination through the rest of the 1970s.

Formal charges were finally made against Luis Echevarria Alvarez and Luis Gutierrez Oropeza for the Tlatelolco murders, and Mario Moya Palencia and Alfonso Martinez Dominguez, among others, for the 1971 attacks. In the end, however, these former functionaries were able to avoid trial after invoking legal technicalities challenging the ability of prosecutors to indict them. In reality, the political system itself was reluctant to unearth a network of responsibility that would have spread to include many others. Nevertheless, Raúl Álvarez and his two co-complainants felt their work made plain to the Mexican people the terrible acts of repression that had cost many lives, and who had given the orders for them.

Bringing up the rear of the October 2 march were members of the only union visibly present-the Mexican Electrical Workers (SME). Both Álvarez and this union have been anchors of left-wing politics in Mexico City. For twenty years the SME campaigned to stop the Mexican government from turning over the nationalized oil and electrical power industries to private corporations. To neutralize its opposition, the SME’s 44,000 members were fired five years ago. The PAN administration of Felipe Calderón ordered the army to occupy the generating stations and declared the union “non-existent.” When the PRI came back into power last July, it pushed through a constitutional amendment permitting the privatization.

Raul would have pointed out that there is really no difference between the pro-corporate policies of PRI and PAN. He fought to keep parts of the PRD from supporting the same privatization reforms. Just days before his death, a delegation of SME leaders went to his home in Mexico City, and gave him a union card, making him member #16,600. He told them he was proud to be a member of this “union in resistance.”

Reflections of Raul Alvarez Garin himself:

A 2002 discussion with Raúl Álvarez Garín, a survivor of the 1968 student massacre, on the ongoing legacy of state impunity in Mexico.

Every year on October 2 thousands of Mexican students pour into the streets of Mexico City, marching from Tlatelolco plaza through the historic downtown to the Zócalo. They’re remembering the hundreds of students who were gunned down by their own government in 1968, an event that shaped the lives of almost every young person in Mexico during that time.

Raúl Álvarez Garín was one of those students whose world changed at Tlatelolco. He was a leader of the national student strike committee, organizing campus walkouts and street mobilizations through the spring of 1968. This rebellious upsurge occurred simultaneously with student protests in France, the United States, and across the globe. When the Left resurfaced after a period of extreme repression in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Álvarez became a leader of the Mexican Left, publishing the leftist magazine Punto Critico, Corre la Voz and numerous articles. For more biographical information, see the 2014 article “A Hero of Tlatelolco.”

In 2014, the commemoration march took on even greater significance. It occurred just days after the disappearance of the 43 Ayotzinapa students, who had commandeered buses to travel to the march but were kidnapped and murdered before they left Guerrero. Álvarez Garín himself had passed away after a battle with cancer on the same day-September 26, 2014. His photograph graced a banner at the head of the march. If he had been alive, he would undoubtedly have been in front of the march himself, pointing out that the impunity of the Mexican state in 2014 has legacies in the impunity of five decades before.

The following interview, conducted on December 1, 2002, contains Álvarez Garín’s reflections on the massacre. At the time, he and others were seeking to bring the perpetrators of the massacre to trial on the heels of the PRI’s historic presidential loss after 71 years in power. On the 50th anniversary of this tragedy, his words bear remembering. His oral history is reprinted in abridged and edited form, below:

In 1968 I was at the school of Mathematics and participated in the Consejo Nacional de Huelga (National Strike Council, CNH) as the school representative. The 1968 movement was against government repression. It grew very large but ended tragically with the events of October 2. That culminated in the arrest of many students and professors.

In order to explain the events of Tlatelolco, you can discuss at length every event leading up to them, for example, the actions taken by both the student movement and the government. There were student marches and dialogues between the two sides. There was also an effort by the government to blame the president of the university for the actions of the students.

Today there are discussions of whether or not these actions were indeed genocide. You can also discuss the resources used by both sides. There was the military occupation of the university. The movement was gaining strength when the government then decided to use excessive force. It was a planned attack using the element of surprise, which is against the law. It meant the death of political opponents. Today there are discussions of whether or not these actions were indeed genocide.

You can also look at Tlatelolco in theoretical terms. The PRI, the ruling political party at the time, had a way of repressing social movements using a firm hand. But it also wanted to be seen as a democratic government. There were many discussions between both sides until the tragic end.

After the massacre of October 2, the government opened the door to this new response method. In essence, it allowed the government to respond in the same way in the future. On June 10 it happened again. Ultimately it led to the formation of the White Brigades, an illegal entity with permission to kill political opponents. In legal terms, we are saying that from October 2, 1968, to 1982, which was the last documented existence of the White Brigades, there existed in Mexico a sort of political genocide. A decision was made to combat a sector of the population, the political opposition. The conflict between society and the government resulted in the extermination of the opposition.

The explanation given by the government is what we call the official version of the events of October 2. They first alleged that there had been a confrontation in Tlatelolco between guerrilla groups comprised of students and the Mexican military. They said that when the military arrived to break up a student march, they were met by gunfire.

It is the same explanation they give for the events of June 10, 1971. They also try to present that situation as a confrontation between two different student groups with different ideologies. They say that the police decided to not intervene. The truth is very different.

When you talk about repression by the Mexican government, it follows a constant line, that the student groups always attacked the military. This is presented as a rebellion or an act of violence that the military had to crush. This is how they explained the events of Tlatelolco.

They explained the events of September 15, 1961, in San Luis Potosí in the same way. At the time San Luis Potosí was a very important railroad town. It was relatively small, with about 300,00 to 400,00 people, but had a large number of 8,000 railroad workers. San Luis Potosí was the hub of the railroad industry of Mexico at the time. In 1959 there had been a nationwide railroad workers’ movement centered in the area. This movement was crushed as well. One of the reasons for Dr. Salvador Nava’s movement was to release all of the political prisoners from the railroad movement of 1959. In 1961, Dr. Nava decided to run in the elections. He won in the city, but the state was still controlled by the PRI.

The government declared to the rest of the country that [Nava’s movement] was an extreme right-wing movement. That legitimized its actions. In order to crush Dr. Nava’s political opposition campaign, the government utilized the same script. The military came in during the night, while the Independence Day festivities were underway. Police, armed and dressed as civilians, started shooting and the military stepped in. Many people died and were injured. This allowed the government to prosecute and jail the leaders.

The same government officials who led this campaign then led Tlatelolco. The government characterized the movement there as the opposite, that they were crushing opposition of the extreme left wing. We say there is a Mexican school of oppression because they have a certain way in which they always respond to situations like this. In ideological terms, the government states that these groups were not made up of students, but instead were guerrilla groups or subversive agents, communists, or terrorists. When the labels escalated as they did, they felt their actions were justified.

It is the same tactic used during the Spanish Inquisition. It is like saying the government’s opponents are not Christians. They are Jews, they practice a twisted belief and are the devil. Therefore, it is justifiable to burn them alive. It is a sequence of actions that they follow to oppress people.

In Atenco, it was the same. They are not agricultural workers, the government said. They are guerrillas. Everything was in place to respond in the same way. They don’t explain the situation as frustrated agricultural workers who are victims of the social, political, and economic situation in Mexico. They define their opponents as a threat to authority. Therefore, they have to respond.

There are two kinds of incidents. One is used to crush movements in the universities and the other to crush agricultural worker movements. There were conflicts in the Universities of Michoacán, Nuevo León, Sonora, Puebla, Tabasco, and Guerrero. They all were suffocated by military action. There were massacres in Chilpancingo in 1960 and 1967. The government’s actions grew increasingly violent. By the time of the movement of 1968 the government had already taken military action against all of these groups.

The government jailed 50-60 students they labeled as communists, even though the students had done nothing illegal. In July that year, the government detained part of the communist group and student opponents of the government. They did not want protests and marches during the Olympics. The student groups continued to call for marches. The government jailed 50-60 students they labeled as communists, even though the students had done nothing illegal. Before the visits of foreign dignitaries like President Kennedy, or other big events, the government wanted to be sure there would be no student uprisings. They conducted preventive detentions of many students who had done nothing wrong. There were deaths, but nothing is documented. The National University was invaded on September 18 and confrontations took place at the Polytechnic University on September 23 and October 2.

The invasion of the Polytechnic University didn’t crush the movement. Instead, the movement grew, incorporating other sectors in the protests. After the confrontations at the university on September 18, the movement began to receive support from workers. There were work stoppages at hospitals and schools in Mexico City. There were railroad worker stoppages. On October 2, a large number of railroad workers arrived in the city to join the marches. Petroleum and electrical workers also supported the student movement. Newspapers declared their disagreement with the government actions. Huge banners hung on buildings throughout the city expressed anger at the police.

The events that took place in the Plaza of Tlatelolco were very complex and all of us there have our personal view of them. Students who had the best view of the day were the ones in the meeting on the third floor of the Chihuahua building. They saw what was happening in the Plaza only for a few seconds. It was a peaceful meeting and when they saw the massacre begin to unfold, they were immediately apprehended. They saw the police on the third floor begin to randomly shoot down towards the plaza, at the military and students alike. Everyone dropped to the floor.

I was in the Plaza and I observed police shooting down on us as the military approached from behind. The first reaction of some students was to try to advance to the third floor and assist our friends there because we couldn’t see them anymore. We were denied access by government agents. They were shooting, and we retreated again to the plaza. Students ran toward Manuel Gonzalez Street, which was then the only exit from the Plaza. Some of us ran inside the church, where we were later surrounded and apprehended. Each person had only a very partial view because none of us could see the entire event.

A very important document was published three or four weeks afterward, which began circulating on October 27 and 28. It was a reconstruction of the events by the National Strike Council. It corresponded with our defense version in 1970, and we have been saying the same thing all of these years. From the first moment, we noticed there were three barricades. The first barricade was around the Chihuahua building which was put in place on orders of Ernesto Gutiérrez Gómez Tagle. He was responsible for blocking access to the building and for the strategically-placed officers in civilian wear. That was a crime.

The second barricade was around the entire plaza and led by Commander José Gómez Toledo. They had three battalions of military officers, which totaled 4,000 to 4,500 soldiers. The third barricade was around the entire property of Tlatelolco, which was led by Cristóforo Mazón Pineda, the leader of the First Brigade in the Mexican military. In that post, there were approximately 4,000 soldiers. This gives us an idea of the magnitude of the operation.

The first shooting started at 6:10 [PM] and ended at 8:30. There were two and a half hours of continuous shooting by hundreds of firearms. The operation lasted a long time. It wasn’t something that happened only once and very quickly, like an explosion or a single gunshot. It was two and a half hours of an extensive military operation. They had sufficient time to make decisions one way or another. The actions they took were planned. It was not out of their control. It was very well planned out.

The time from the moment the shooting started until the Plaza was empty, except for the bodies of the dead and wounded, was not more than two minutes. From there on, action proceeded at the Chihuahua building, where there were snipers on the third floor. We are waiting for the explanation of the government about these individuals who shot at targets for two and a half hours. What was their purpose? For those of us in the Plaza, it was very evident that it was an oppressive measure by the government. The soldiers shot at the building and at anything that moved. I was very angered by what I saw.

When the shooting started, David Vega was talking. We were in the corner by the mural and the convent. The soldiers were a few meters away. I left immediately and when I turned I saw a group of people where I had been standing, who were injured or dead, including a child. At that moment I couldn’t stop and reflect. It was different at the military detention center where we were all taken. For the first few days, I was under the impression that all of our fellow students on the third floor of the building had been killed. Fortunately, that was not the case.

I was detained in Tlatelolco. All of my fellow students in the Chihuahua building were immediately taken to the military detention center as a group. I was taken with another group to Santa Martha. They then realized that I was to have taken part in a meeting with them. They transferred me to the military detention center but isolated from the group. The other students didn’t know I was detained there and vice versa. We knew we were political prisoners and we would not be liberated immediately. I was detained for two years and seven months.

People became more aware of the many illegal atrocities taking place, and as a consequence, many decided to form a new political movement against the ruling party. The movement of 1968 triggered a change in the mind of many Mexicans. People became more aware of the many illegal atrocities taking place, and as a consequence, many decided to form a new political movement against the ruling party. Many committees started popping up. All of this activity spurred political participation and popular opposition to the administration. In 1971 President Díaz Ordaz left office, and Luis Echeverría became president, beginning a series of changes. Prisoners were freed, from both the railroad movement and our movement.

Some students were released in January and February. We were released in April, but we had to agree to leave the country. Our only condition was that we could decide which of us would leave the country first. We left to Peru and Chile, another chapter of our political struggle. Students with longer prison terms were the ones who left the country. That way students with shorter prison terms would have to be released and allowed to stay. After we were released in April, the students who were already free and in Mexico began a campaign, charging that we had been exiled. We used a quote from Porfirio Díaz, which referred to the treatment of political opponents, which called for imprisonment, banishment or death. The government said we hadn’t been banished from the country and that they had not forced us to leave. They said we had a choice, so we then changed our minds and returned to Mexico on June 3, 1971.

Seven days later was the massacre of June 10. The movement of June 10 began at the University of Nuevo León. It called for a change in the political structure, with many issues. A march was scheduled in Mexico City to support the students in Nuevo León. The government used the march as an opportunity to attack with a paramilitary group called the Falcons. They were dressed as fellow protesters, and then suddenly attacked. A total of 37 people died, possibly more.

The government stated that the students who returned from Chile had provoked it and caused another confrontation. That excuse didn’t hold up very well. The press immediately told another story and showed the planned coordination between the Mexico City police, the National military and the Falcons. Their government made an investigation but the findings were never reported.

In those days, the government would arrest you for two reasons. One was because you belonged to the Communist Party, and the other was because you were a leader in the student movement. Either was enough to be detained. The formal accusations depended on the moment. The students who were detained in July 1968, were charged with minor offenses, like robbery and illicit activities. As time went on, more serious charges were made. After September, the government began charging them with rebellion. After October 2, the charges included homicide. We were accused of 12 charges, which included robbery, illicit activities, rebellion, and homicide. The trials of 1968 were ridiculous. The prosecutor at the time has admitted that these charges were bogus, with no foundation. He became a witness for us, in order to dismiss those charges.

Yet Echeverría’s image is associated with left-wing movements in Latin America. At that time, Mexico welcomed political exiles from Chile, like the family of Salvador Allende, and received a large number of Argentine and Brazilian exiles. Mexico was seen as a leader in Latin America. This is not in contradiction with extreme nationalism, a nationalism very close to fascism. But it put opposition groups in Mexico in a very difficult situation. For many years Mexico was seen by other countries as a very positive and democratic government since it was receiving political exiles. That made opposition groups in Mexico seem extremely radical. If you were not completely aware of Mexico’s situation it was easy to be fooled.

Another event like October 2 is not completely out of the question. Every time there is an uprising, the possibility of this happening is still present. We have been saying for the last 30 years that this action to stop. In 1988, with the victory of Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, the same thing could have happened when they voided his win. In his speech, he stated, “they want a bloodbath.” But the same oppression could not happen again, he said, because we were going to build a party so big and united that they would have to retreat.

In 1993, a year before the elections of 1994, some said the two giant trains would collide-the PRI and the PRD, with its leader Cuauhtémoc Cardenas. Many feared that the PRI would use deadly force again. That year a commission was formed to find final answers about the events of Tlatelolco. They didn’t have access to government documents, however. The government stated that for national security reasons they could not release military documents for 30 years. So we waited until 1998 when again a commission was formed to investigate the events, and once again they were denied information. Nevertheless, we made our own study and conclusions about what happened, with the purpose of prosecuting those responsible for the massacre.

Some people still say that excessive force is justified to pacify opposition groups. The only way to have people punished for their actions is to try them in the justice system. We had to say that we weren’t interested in the reasons the government had for taking actions. What we wanted was an investigation to determine whether certain actions on October 2 warranted criminal charges.

We presented the charges, and at first, we were not taken seriously. But the international community began looking at human rights issues seriously, like the Pinochet case. The situation changed. Now it is not as easy to dismiss our charges. They must respond to them.

Naturally, the judicial system tried to change or modify the cases, so that our side would get frustrated. The press responded favorably to us because they had also been affecting by censorship. At the center of everything was the military, and many have concluded that there must be a code of ethics in the Mexican military. The way the system works is that the military obeys all government orders blindly. We want them to have loyalty first and foremost to the nation and the law, not to their supervisors. This is a national cultural battle. An article in the newspaper La Jornada said this new idea should be taught and implemented in military schools.

During those years Mexico maintained a distance from the U.S. government. Until 1968 the Mexican military was trained to stop aggression from the United States. This had always been their frame of mind and didn’t start to change until then. After 1968 new elements were incorporated, like taking a stance against national subversive groups like the Communists. Until 1976, Mexico did not participate in military conferences in Latin America. Nevertheless, there was some collaboration between the U.S. and Mexico.

After the attacks of September 11, the United States has asked for much broader cooperation from other countries. They have asked for intelligence information from their borders and the activities of possible terrorist movements and groups. They have a very broad definition of what they define as terrorism. All of this has to have some effect on intelligence and military factions of Mexico. This is alarming because the people who hold offices in the intelligence community in Mexico is a relatively small group. That will be reflected in the outcome of the trials. These trials will have to investigate the intelligence community. They are the ones that gave information to the government, which in turn made decisions based on that information.

In 2002, a special prosecutor was appointed in the case filed by Alvarez Garin, Jesus Martin del Campo, and Felix Hernández Gamundi, but in 2007 a court hearing the case dismissed it. Following the election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of Mexico, however, hope increased that the case could be revived. On September 24 of this year, the government issued a statement that confirmed that the Tlatelolco shootings constituted a massacre. As Jaime Rochin, chief of the Executive Commission for Victims’ Assistance in Mexico (CEAV), a subsidiary of the Department of the Interior, wrote: “The Tlatelolco massacre, which took place on the afternoon of Oct. 2, 1968…represents a historical chapter in which the Mexican state showed its most authoritarian face by silencing the voices of the citizen’s movement.”

David Bacon is a California writer and photographer, with numerous published articles about Mexican politics and labor. His latest book is In the Fields of the North / En los campos del norte (University of California Press / Colegio de la Frontera Norte, 2017). He was a friend of Raúl Álvarez Garín.