On October 10, 1868, Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, an educated, wealthy lawyer, sugar mill and slave owner, called for an uprising against Spanish colonial rule, the “Grito de Yara” (Cry of Yara), otherwise known as the “declaration of rebellion.”

The date continues to define Cuba’s national identity and is seen as the start of the Cuban people’s struggle for independence; the late Fidel Castro called the date the “beginning of the revolution.” October 10—Independence Day—is an annual public holiday. Céspedes is renowned as “Father of the Homeland,” and Cuba’s national anthem, La Bayamesa, was also written in the same period, a century and a half ago.

Céspedes released the slaves owned by his family following the Grito de Yara and called for the abolition of slavery, reportedly urging the crowd of 500 people at his La Demajagua sugar mill to rise up against Spanish rulers, who had colonized the island since the beginning of the 16th century.

“Citizens, that sun you see rising above Pico Turquino comes to illuminate the first day of Cuba’s freedom and independence,” Céspedes is said to have told the crowd.

The Ten Years’ War, Cuba’s first war of independence, followed the declaration.

In the eastern town of Bayamo, following a rebel victory against the Spanish in the Battle of Bayamo, Céspedes became the first “president of the Republic in Arms” in 1869.

Slavery and the independence struggle

In addition to independence, the abolition of slavery was a key issue in the war.

In 1868, Cuba was producing 40 percent of the world’s sugar, and slave labor was creating significant riches for white landowners.

Although slavery was officially illegal in the U.S. by this time, U.S.-flagged vessels played a crucial role in the illegal slave trade to Cuba and Brazil. U.S. cities, including Boston and Baltimore, were built on the huge profits made by U.S. slave traders who were reportedly still bringing slave ships into Cuba until 1876—eight years into the Ten Years’ War.

A wave of slave liberations followed the October 10 declaration and large numbers of black Cubans actively fought for their own freedom and for an end to slavery as well as for independence.

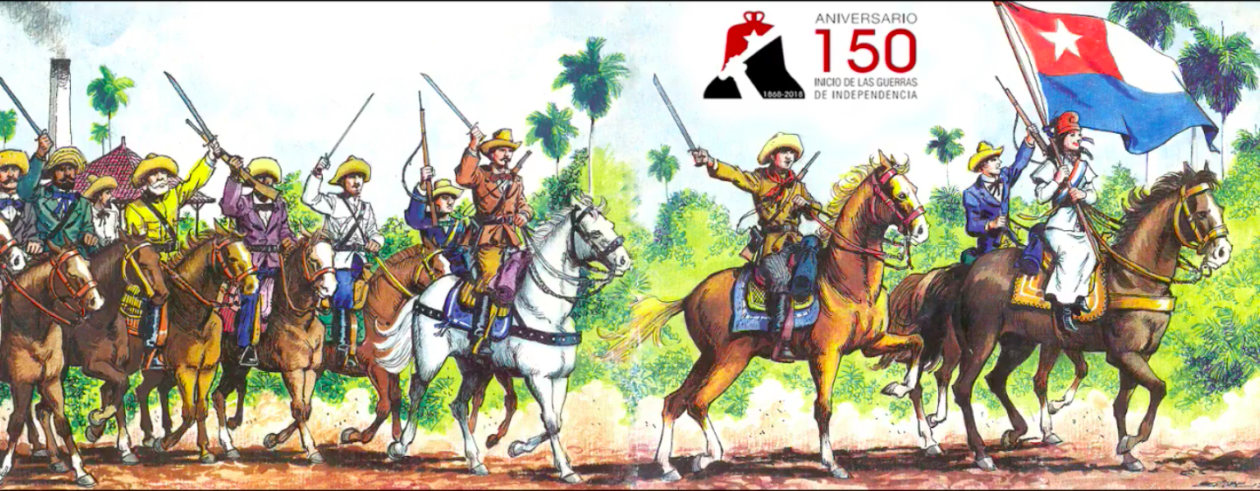

The “mambises” rebel army was comprised of thousands of black Cubans, in addition to Cubans of Spanish and Chinese descent, alongside a small number of white landowners who had also freed their slaves.

While Céspedes is called the “Father of the Homeland,” Mariana Grajales is renowned as the “Mother of the Homeland.” The Afro-Cuban Grajales family serve as an iconic symbol of Cuban independence and Afro-Cuban resistance to colonial oppression.

Mariana Grajales operated a rebel mountain settlement and field hospital and was renowned for entering battlefields to rescue and treat wounded soldiers.

Her son, Antonio Maceo Grajales, is arguably a more revered hero than Céspedes in Cuba. Maceo was second-in-command of the independence army and was said to be heroic on the battlefield, a master of military strategy, and was known as “the bronze titan” by his comrades.

They faced the huge force of the Spanish army, with an estimated 250,000 heavily armed Spanish soldiers sent to quash the rebellion, which numbered closer to 12,000 mambises. The Spanish were supported by many recent white Spanish settlers on the island, who were determined to maintain slavery and were given free rein to respond with brutality to the uprising.

In addition to being greatly outnumbered, the mambises also faced challenges from divisions on their own side.

As more regions joined the independence struggle, disagreements emerged on the battlefield and different visions of independence emerged. Some factions wished to annex Cuba to the U.S., while others, including Maceo, wanted true independence from foreign powers and were aware of the threat posed by U.S. interests in maintaining slavery on the island.

Céspedes was ousted as president of the Republic of Arms by other independence figures in 1873 and was killed by Spanish forces the following year. Over 20 members of his family are said to have died for Cuba’s independence, including the infamous case of one of his sons, Oscar.

Oscar was captured and held hostage by the Spanish in an attempt to blackmail his father into renouncing the call for independence. It is said that Carlos Manuel de Céspedes wrote in a defiant letter of response: “Oscar is not my only son, I am the father of all the Cubans who have died for Cuba.” Oscar was executed on June 3, 1870.

The Ten Years’ War ended with neither side “winning.” The Pact of Zanjon brought a truce to the war in 1878 but didn’t achieve independence or the full abolition of slavery.

For Antonio Maceo, the Pact of Zanjon was a betrayal of the aims of the independence insurrection—it did not bring the end of slavery in Cuba nor independence—it only included an amnesty and freedom for the black soldiers who had fought in the war.

Maceo responded by calling a conference now known as the Baragua Protest, but the rebellion was not large enough to continue the armed struggle.

Why did the independence war fail?

José Martí, who was a teenager during the Ten Years’ War, said the war was lost “not because the enemy wrenched the sword from our hand, but because we let it drop.”

Following the splits that emerged in the Ten Years’ War, unity became a key aim for Martí. The focus on unity against foreign intervention in Cuba remains today.

Martí is largely credited with helping bring unity among Cubans in their independence struggle. Just seven years after the end of the first war, in 1895, the next war of independence began, and Martí was killed.

This war proved to be successful in defeating the Spanish, but the Cubans ended with another imperial power effectively in control of their affairs—the United States, after its late intervention.

On May 20, 1902, following the U.S. intervention in the war against the Spanish, a faux-independence agreement was signed with the U.S.

The agreement allowed the U.S. the right to intervene in Cuban affairs through the infamous Platt Amendment and gave the U.S. an indefinite lease of Cuba’s Guantanamo Bay. May 20 is still annually commemorated as Cuban “independence day” by the U.S. president and the hardline anti-Cuba Florida politicians, including Sen. Marco Rubio—a celebration of a date when the U.S. retained control of Cuba.

The legacy of October 10

One hundred and fifty years ago, Céspedes’s declaration started the highly improbable task of defeating a global superpower with hundreds of thousands of well-armed soldiers.

But it was the courage of the original independence movement that helped inspire the successful Cuban Revolution in 1959. Céspedes’s movement confirmed the “axiomatic truth,” Fidel Castro said, “that if to fight we first have to await ideal conditions, all the necessary weapons and supplies, then the struggle would never have started.”

And the leading role played by black Cubans, who eventually won their own freedom and the abolition of slavery, cannot be understated.

Like 1868, the conditions were certainly not ideal on July 26, 1953, for Castro and his fellow revolutionaries when they launched an attack on the Moncada Barracks.

The Moncada attack and the Grito de Yara both were failures in their military aims but led to a movement that finally triumphed on January 1, 1959.

Speaking at the United Nations General Assembly last month, Cuba’s new President Miguel Diaz-Canel also tied in the events of October 10, 1868 and the 1959 Revolution as two events of the same struggle: “The country will not go back to the opprobrious past that it shook off with the greatest sacrifices during 150 years of struggle for independence and full dignity. By the decision of the overwhelming majority of Cubans, we shall continue the work that started almost 60 years ago.”

Morning Star