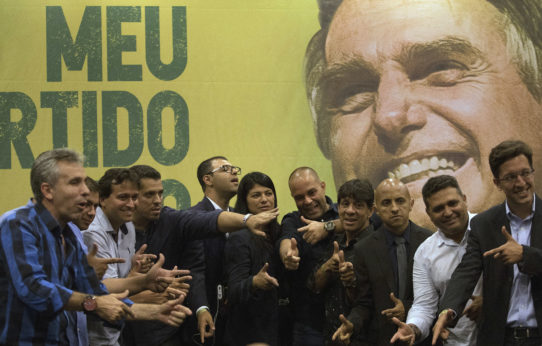

The advance of the extreme right-wing candidate Jair Bolsonaro in the first round of the Brazilian presidential election confirms the global threat of the growth of authoritarian reaction. With nearly 50 million votes, 46 percent, it will take an enormous upset for the center-left Workers Party candidate to defeat him in the runoff in two weeks’ time.

Leftists and social movement activists are throwing themselves into trying to bring about such a reversal, with large numbers stung into activity across Brazil—the world’s ninth biggest economy.

Their shock is shared by the labor movement and genuine democrats internationally. Some recall, others have heard about, the “monstrous era” of Latin American politics with its disappearances, military-police terror, and extreme assaults on labor and democratic rights.

That’s one reaction. Another has come from the organs of the international business class.

The paper of conservative U.S. plutocrats, the Wall Street Journal, has gushed with praise for Bolsonaro—who is more classic Latin American caudillo hard man than interwar European fascist (though that in no way diminishes his menace). He is apparently going to “drain the swamp” of political impasse and corruption, and bring free market dynamism to Brazil through tax cuts for the ultra-rich. A Trump in the tropics.

The more cultured and cosmopolitan Financial Times warmed to his economic policy and political assault on the left. It remains an open question how much of a blind eye it will turn to physical assaults on the left if he comes to office, as is likely.

Those embraces point to a fundamental truth. Despite demagoguery, Bolsonaro has not advanced as some kind of pseudo-radical outsider. He is the favored candidate of big business, especially of the climate-destroying extractive industries, and of the military-state apparatus in Brazil.

The standard bearer of capitalist interests in previous elections, Geraldo Alckmin of the Social Democracy Party, this time saw his vote fall from over 40 to barely 4 percent. His support—institutional as well as in conservative votes—went over to a far-right candidate who some have labeled a fascist.

None of this sits with the liberal platitudes that have sought to explain the rise of the radical right in recent years in its varied forms. According to that theory, the authoritarian or even fascist right is but an expression of inchoate populism.

The (neo)liberal economic and political order is under siege and must hit back with rational policy to meet the threat—of both radical right and radical left. Recompose the capitalist center.

But the urbane capitalist order in Brazil has made its choice. It’s decided upon a far-right adventurer as its political instrument to pursue its interests at just the time that a dangerous economic crisis appears to be developing in “emerging markets” such as Brazil.

He, in turn, has surrounded himself both with generals and with gurus of the ultra-free-market Chicago School. Not interwar era corporatism, but turbo-charged 21st-century neoliberalism.

It is no mystery why Bolsonaro cites as one of his heroes Augusto Pinochet—a general whose coup liquidated the left and turned Chile into a pioneering laboratory for exactly that slash-and-burn capitalist economics from the Windy City.

There is a contrast with the rise of the far and fascist right in Europe. The candidates of big business in last year’s French and German elections were Emmanuel Macron and Angela Merkel.

Exit polling showed that the Euro-fascist Marine Le Pen got 8 percent support among members of Medef, the French employers federation.

In Italy, the boss class looked to billionaire and known (if flaky) quantity Silvio Berlusconi and to the Blairite center-left at the election. They ended up with the unknown quantities of the insurgent far-right Lega and the anti-Establishment populist Five Star in an unstable coalition.

The Italian government is now caught in a three-way battle over its budget and economic program: with the EU, with domestic big business, and within itself.

Both the EU and Italian business have hoped that the far-right Matteo Salvini—who favors a pro-oligarch flat tax—will moderate the more welfarist Luigi Di Maio, whose Five Star movement has promised a reflationary budget and guaranteed income for the poor. The outcome of this tussle remains as radically uncertain as the turbulence in the Italian debt market. One thing is clear.

While European and Italian capitalist interests may be worried about the economic direction of the government in Rome, they have been perfectly happy to go along with the racist and authoritarian domestic policy that Salvini has at the center of his political charlatanry.

Indeed, EU leaders adopted at a summit this summer the grotesque anti-migration proposals of Salvini and of Hungary’s Viktor Orban. That deal is breaking down. No north African government worthy of the name is prepared to set up concentration camps for migrants trying to get to Europe.

The resolution of that new crisis is likely to mean yet more barbaric measures and a Dutch auction over migrants’ and refugee rights. That will involve all the EU governments—conservative and liberal.

The whole of the European and British business class is prepared to go along with this. Thus, there are hard-right figures, or even ideologically committed fascists, occupying the interior ministries of Germany, Austria, and Italy—right in the heart of Europe.

The bigger problem for the European far right and its fascist component is in economic policy. Their attempts to build a pseudo-radical following in the era following the great crash of 2008 mean they face all sorts of contradictions in winning the big business and Establishment support they crave and without which they cannot come to command state power.

Le Pen faced this problem last year. Her push-me-pull-you policy on the euro and an incoherent France-First economic program fell apart in the presidential campaign. Capital preferred Macron—to put French capitalism first.

Her Rassemblement National (as the Front National is now called) has moved to resolve the dilemma. A senior fascist MEP, Nicolas Bas, says that it will fight the European parliament elections on themes of nation and “identity.” But it is aimed at hegemonizing the traditional right with its pro-market, pro-capitalist inclinations. Less talk of “national revolutionary” rupture or trying to sound like a fake National-Left.

The AfD in Germany has sought to avoid the dilemma by focusing on increasingly rabid racist and authoritarian rhetoric. That can find political resonance on the right of Merkel’s government.

But the Bolsonaro example, if he wins in the second round, must have an impact: that the way for the far right to advance is by adapting policy to become a direct instrument of big business.

Writing in the current issue of the New York Review of Books, the distinguished historian of Nazi Germany and the Holocaust Christopher Browning reminds us that this was ultimately always a necessary step for the success of the interwar fascist movements.

They could scoop up all sorts of social discontent with reactionary demagoguery. But they came to power only in an alliance with big business and mainstream conservative forces. As the leading bourgeois political player in Germany, Franz von Papen, said upon handing power to Hitler in January 1933: “We hired him.”

Read Georgi Dimitrov’s classic text on the collusion of the capitalist class and fascist movements, Against Fascism and War, available from International Publishers.

They got more than they bargained for. But that does not negate the fact that in extreme circumstances they made, from their point of view, a very rational capitalist bargain. Pleas from well-meaning social democrats that they were making a mistake fell on deaf ears.

Futile too are appeals today to the super-yacht-owning class to hold to “liberal values.” Bolsonaro has an offer to the Brazilian oil and agribusiness giants—physical elimination of indigenous and environmentalist opposition to further destruction of the Amazon region.

What can the left offer? Mixed-economy environmental devastation? No. The left must offer militant opposition—not indifferent to the form of business rule, but fully aware of that if push comes to shove, then big business—as a class—will put dollars over democracy every time.

The neoliberal advance of capitalism in the global South depended 40 years ago upon barbaric South Korean and Egyptian generals, Latin American dictators, de-democratization in India… As in its youth, so in its dotage.

Liberalism has had only ever a passing acquaintance with democracy. Capitalism has proved time and again that it can dispense with both.

That is the urgent lesson from Brazil—now looking politically like it did in the bloody 1970s.

Mobilizations have been and are taking place in Brazil, in Europe, and elsewhere against the far right and fascism. The gatherings are broad and do not demand an expensive entry ticket, literally or figuratively.

At the same time, let’s recall the old German Marxist aphorism: If we are talking about fascism, then we are talking about capitalism.

This is the meaning we must absorb from Brazil.

Morning Star