Today Silicon Valley remains the fortress of the country’s most anti-union industry. High tech industry dominates every aspect of life. Its voice is largely unchallenged on public policy because the workers who have created the valley’s fabulous wealth have no voice of their own. Corporations like IBM, Hewlett-Packard, Intel and National Semiconductor told their workers and communities for years that healthy bottom lines would guarantee rising living standards and secure jobs. Economists still paint a picture of the industry as a massive industrial engine fueling economic growth, benefiting workers and communities alike.

The promises are worthless. Today many giants of industry own no factories at all, having sold them to contract manufacturers who build computers and make chips in locations from China to Hungary. In the factories that remain in the valley, labor contractors like Manpower have become the formal employers, relieving the big brands of any responsibility for the workers who make the products bearing their labels. While living standards rise for a privileged elite at the top of the workforce, they’ve dropped for thousands of workers on the production line. Tens of thousands of workers have been dropped off the lines entirely, as production was moved out of the valley to other states and countries.

Apple Corp. has cash reserves in excess of $1 billion, while San Jose voters are told that there is no money to pay for the pensions of workers who’ve spent their lives in public service. The productivity of industry in the valley went up in the first decade of the current century by 42 percent. But at the same time, average annual employment went down 16 percent. The upper-income stratum of the valley benefited from this productivity growth, but there was no corresponding growth in jobs. Fewer people produced wealth for fewer people. The rich got richer and the poor get poorer. Between 2000 and 2010 the number of households with incomes under $10,000 more than doubled, from 11,556 to 26,310.

To make the economy serve the needs of working families, they must be organized. It’s not enough to have a voice or a “place at the table.” Silicon Valley’s 99% need the organized ability to effectively advocate for their needs, in the face of corporate resistance. But despite obstacles, for its entire history, Silicon Valley has been as much a cauldron of resistance and new strategies for labor and community organizing as it has been for the production of fabulous wealth. Workers have opposed inhuman conditions. Community organizations have fought for social justice and equality. They will keep on doing that.

High-tech builds its anti-union model and workers respond

The anti-communist hysteria of the late 1940s and ‘50s bred a fratricidal struggle in the US labor movement. This led to the expulsion of the union founded to organize workers in the electrical industry—the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE). While the new high-tech industry was growing in the Santa Clara Valley, the union that could have organized it, had it retained its strength and members won in the 1930s, was severely damaged. In the rest of the labor movement, support for workers organizing unions in the expanding plants virtually disappeared.

From the beginning of the electronics industry in the late 1960s, high tech workers faced an industry-wide anti-union policy. “Remaining non-union is an essential for survival for most of our companies…The great hope for our nation is to avoid those deep, deep divisions between workers and management,” said Robert Noyce, co-founder of Intel Corp. The expanding electronics plants were laboratories for developing personnel-management techniques for maintaining “a union-free environment.” Some of those techniques, like the team-concept method for controlling workers on the plant floor, were later used to weaken unions in other industries, from auto manufacturing to steelmaking.

A co-inventor of the transistor and founder of an early Silicon Valley laboratory, William Shockley, espoused theories of the genetic inferiority of African-Americans. As Shockley, Noyce and others guided development in the Valley, they instituted policies that effectively segregated its workforce.

In electronics plants, women were the overwhelming majority, while the engineering and management staff consisted overwhelmingly of men. Immigrants from Asian and Latin American countries were drawn to the Valley’s production lines. Engineering and management jobs went to white employees. African-American workers were frozen out almost entirely. Although unemployment in the African-American communities of Oakland and East Palo Alto, within easy commuting distance of the plants, has remained at depression levels, African-Americans are still not above 7.5 percent of the workforce in any category, and below 3 percent in management and engineering.

Starting in the early 1970s, workers began to form organizing committees affiliated to the UE in plants belonging to National Semiconductor, Siltec, Fairchild, Siliconix, Semimetals, and others. Most of these were semiconductor manufacturing plants or factories that supplied raw materials to those plants.

“It was very hard organizing a union in those plants because the feeling of powerlessness among the workers was so difficult to overcome … It seems obvious that there has to be a long-term effort and commitment, with a movement among workers in the industry as a whole, and in the communities in which they live,” said Amy Newell, who helped start a rank-and-file organizing committee at Siliconix, and later headed the AFL-CIO’s Central Labor Council in Monterey County, just south of Silicon Valley. .

By the early 1980’s, the UE Electronics Organizing Committee had grown to over 500 workers. Romie Manan, who organized Filipino immigrant workers on the production lines at National Semiconductor, remembers that the union published 5000 copies a month of a newsletter, “The Union Voice,” in three languages—English, Spanish and Tagalog. Workers handed it out in front of their own plants, or in front of other plants if they were afraid to make their union sympathies known to their coworkers. “A few of us were aboveground, to give workers the idea that the union was an open and legitimate organization, but most workers were not publicly identified with the union,” Manan recalled.

Committee members challenged the companies and won cost-of-living raises, held public hearings on racism and firings in the plants, and campaigned to expose the dangers of working with numerous toxic chemicals—all without a formal union contract.

Eventually, the semiconductor manufacturers, especially National Semiconductor, fired many of the leading union activists, and the committee gradually dispersed as its members sought work wherever they could find it. The main strategic question, which the committee sought to answer, remains unresolved. In large electronics manufacturing plants, union-minded workers are a minority for a long period of time. Their organization has to be active on the plant floor to win over the majority of workers by fighting around the basic conditions that affect them. But it has to be able to help its members survive in an extreme anti-union climate.

This long-term perspective is very different from the organizing style of most unions today. Many view union organizing as a process of winning union representation elections administered by the National Labor Relations Board. Others try to use outside leverage to force management to remain neutral while workers sign union cards, and eventually negotiate a contract. In high tech, however, huge corporations insulate themselves from their production workforce so well that outside pressure has little effect on them. Most unions have simply abandoned the idea of helping workers in those plants to organize at all, saying that they are “unorganizable.”

Despite its lack of success in organizing permanent unions, the UE Electronics Organizing Committee was a nexus of activity from which other organizations developed. The Santa Clara Committee on Occupational Safety and Health (SCCOSH), originally founded by health and safety activists in the late 1970s, fought successfully for the elimination of such carcinogenic chemicals as trichloroethylene, and for the right of electronics workers to know the hazards of toxics in the workplace. SCCOSH sponsored the formation of the Injured Workers Group, which organized workers suffering from chemically induced industrial illness. The group’s lawyer Amanda Hawes (also the lawyer for the Cannery Workers Committee) is still filing suits against the electronics giants.

“When we talk about organizing,” explained Flora Chu, then the director of SCCOSH’s Asian Workers’ Program, “we have to talk in a new way. Many immigrants, for instance, aren’t used to organizing in groups at work. SCCOSH helps to introduce them to the concept of acting collectively. The organization of unions in the plants will benefit from this if unions are sensitive to the needs and culture of immigrants.”

The Silicon Valley Toxics Coalition also grew out of the health and safety campaigns that ripped apart the image of the “clean industry,” exposing large-scale contamination of the water by electronics manufacturers. Coalition activists forced the Environmental Protection Agency to add a number of sites to the Superfund cleanup list.

In 1982 the UE committee tried to mobilize opposition to the industry’s policy of moving production out of Silicon Valley. In 1983 the plants employed 102,200 workers; they employed only 73,700 people ten years later. While the number of engineers and managers increased slightly, job losses fell much more heavily on operators and technicians. “What this really meant,” said Romie Manan, “was that Filipino workers, in particular, lost their jobs by the thousands, more than any other national group.” Manan lost his job as National closed its last mass production wafer fabrication line in the Valley in 1994.

Employers turn to contractors, unions to new tactics

In 1993 Intel built a new $1 billion plant in Rio Rancho, New Mexico, instead of California, because New Mexico offered $1 billion to help finance construction. Lower wages were another determining factor. In Silicon Valley, the more permanent jobs in the large manufacturing plants began disappearing. But contractors who provided services to large companies, from janitorial and food services to the assembly of circuit boards, employed more workers every year.

Workers losing jobs in the semiconductor plants made as much as $11-14/hour for operators, even in the early 1990s when the minimum wage hovered just above $4/hour. Companies provided medical insurance, sick leave, vacations and other benefits.

By contrast, because contractors compete to win orders by cutting their prices, and workers’ wages, to the lowest level possible, contract assemblers and non-union janitors got close to the minimum wage, had no medical insurance, and often no benefits at all. The decline in living standards made the service and sweatshop economy in Silicon Valley the subsequent focus for workers’ organizing activity.

In Fall 1990 more than 130 janitors joined Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Local 1877 during an organizing drive at Shine Maintenance Co., a contractor hired by Apple Computer Corp. to clean its huge Silicon Valley headquarters. When Shine became aware that its workers had organized, it suddenly told them they had to present verification of their legal immigration status in order to keep their jobs. Shine’s actions ignited a yearlong campaign, which culminated in a contract for Apple janitors in 1992.

Other employers in the Valley closely watched the campaign at Shine and Apple. Using the same strategy, SEIU went on to win a contract for janitors at Hewlett-Packard Corp., an even larger group than those at Apple. The momentum created in those campaigns convinced other non-union janitorial contractors to actively seek agreements with Local 1877, and over 1500 new members streamed into the union.

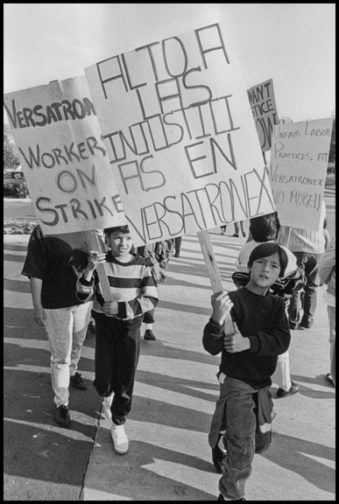

In September 1992, electronics assembly workers at Versatronex Corp. used a similar strategy to organize against the sweatshop conditions prevalent in contract assembly factories. The starting wage at the plant was $4.25 per hour, the minimum wage at the time. There was no medical insurance. Sergio Mendoza worked in the “coil room,” making electrical coils for IBM computers for seven years. “Sometimes the vapors were so strong that our noses would begin to bleed,” he said. The conditions in the “coil room” were very different from those at the facilities IBM had at the time in South San Jose, which is referred to as a “campus.”

Contract assembly provides a number of benefits for large manufacturers. Contractors compete to win orders by cutting their prices, and workers’ wages, to the lowest level possible. Today the contract assembly system, then in its infancy, has come to dominate high tech industry. Corporations like Hewlett-Packard and Apple have no factories at all. Their entire production is carried out by contract manufacturers in plants around the world.

Workers at Versatronex workers went on strike after the company fired one of their leaders, and later launched a hunger strike and Occupy-style encampment, or planton.”It is not uncommon for Mexican workers to fast and set up plantons—tent encampments where workers live for the strike’s duration,” said Maria Pantoja, a UE organizer from Mexico City. “Even striking over the firing of another worker is a reflection of our culture of mutual support, which workers bring with them to this country. Our culture is our source of strength.”

Tactics like those used at Apple, USM and Versatronex have been at the cutting edge of the labor movement’s search for new ways to organize. They rely on alliances between workers, unions and communities to offset the power exercised by employers. Often they use organizing tactics based on direct action by workers and supporters, like civil disobedience, rather than a high-pressure election campaign that companies frequently win. As workers organized around conditions they faced on the job, they learned to deal with issues of immigration, discrimination in the schools, police misconduct, and other aspects of daily life in immigrant communities.

Electronics manufacturers have been forced over the years to permit outside contract services, like janitorial services and in-plant construction, to be performed by union contractors. Nevertheless, the industry has drawn a line between outside services and the assembly contractors who are part of the industry’s basic production process. In one section, unions can be grudgingly recognized; in the other, they will not be. Workers, communities and unions need a higher level of unity to win the right for workers to organize effectively in the plants themselves.

In the heyday of the UE Electronics Organizing Committee, the National Semiconductor plant had almost ten thousand workers, working directly for the company. By the time Romie Manan was laid off, employment had fallen to 7000. Over half worked for temporary employment agencies, including almost all production workers. Manpower, the temp agency, had an office on the plant floor. According to Mike Garcia, the late president of SEIU Local 1877, “high technology manufacturing doesn’t create high-wage, high-skill jobs. It patterns itself after the service sector. Contractors in manufacturing compete over who can drives wages and benefits the lowest.”

David Bacon is a journalist and photographer in San Francisco. He is a member of the Editorial Board of International Union Rights. He was chairperson of the UE Electronics Organizing Committee in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and an organizer for the UE at Versatronex.