TORONTO—It gets frustrating attending film festivals looking for progressive or revolutionary cinema. Human stories dealing with urgent social and personal issues are in abundance, especially now that everyone has easy access to a camera and there appears to be no lack of victims to study. Many are great works of art that draw viewers into their stories demanding an emotional or political resolution. But very few even suggest that the ills of society might be caused by the social system itself. An anti-capitalist or anti-imperialist approach is rare. Even the films that do critique capitalism and its endless path toward war and destruction around the world and at home, suggest the solution is that we just need to fix the system—vote someone in or out, support this non-profit or that corporate entity, change this law or that—but never fight to replace it with a more humane and just system.

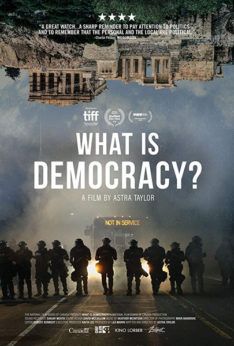

One of the more outstanding films at the 2018 Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) directly addresses these issues, but in a more philosophical manner than usual. Winnipeg filmmaker Astra Taylor, director of two previous challenging films, Zizek and Examined Life, has added another gem to her credits. What Is Democracy? is not your normal festival fare, certainly not for the escapist film buff. It’s as much a historical analysis of the term’s derivation as an attempt to further define it through interviews. The probing documentary delivers a heady examination of a term that is often abused and misunderstood, and a few of our favorite current thinkers are involved in the exercise—Cornel West and Angela Davis, to mention just a couple.

One of the more outstanding films at the 2018 Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) directly addresses these issues, but in a more philosophical manner than usual. Winnipeg filmmaker Astra Taylor, director of two previous challenging films, Zizek and Examined Life, has added another gem to her credits. What Is Democracy? is not your normal festival fare, certainly not for the escapist film buff. It’s as much a historical analysis of the term’s derivation as an attempt to further define it through interviews. The probing documentary delivers a heady examination of a term that is often abused and misunderstood, and a few of our favorite current thinkers are involved in the exercise—Cornel West and Angela Davis, to mention just a couple.

Capitalism is commonly, if wrongly, defined as “rule by the people,” but this “rule” could mean through several different methods, and not only through the voting box. In capitalist countries where representative democracy allows select citizens who meet the qualifications to vote for often pre-selected candidates, the results are often that major decisions are made without the input of those same citizens.

In a world of class struggle, Karl Marx defined two types of democracy—bourgeois and proletarian, often currently defined as corporate and people’s democracy. The film doesn’t address how the word has been co-opted by the West, which often uses “freedom and democracy” to justify attacking and overthrowing other nations, while covering up for a totally unjust duopoly. Taylor’s attempts to address the various meanings and applications of the term are rewarding viewing, and another educational and entertaining product from the revered National Film Board of Canada.

What you gonna do?

Another “What” film shown at TIFF18 deserves special attention. What You Gonna Do When the World’s On Fire? takes place in three Southern U.S. cities: Jackson, Miss., where the New Black Panthers are going door to door organizing around a local lynching; a Texan town where two young bonded brothers, Ronaldo and Titus, and their mother are trying to steer clear of gun violence which is incessantly prevalent in their community and daily lives; and New Orleans, where a drug addict turned bar owner, Judy Hill, is trying to save her club, the famous Oo Poo Pah Do. This is another amazing film by Roberto Minervini, who offers one of the best immersions into Black culture that the movie camera has ever captured. Brutally honest scenes caught by an almost invisible camera as African Americans struggle to deal with racism, violence, gentrification and poverty, are made surprisingly possible by the fact that the white filmmaker has been totally assimilated into the Black communities he films. A harrowing scene with a devastated crack addict in NOLA, an insider’s view of the New Orleans Mardi Gras Indian culture, Panthers going door to door to alarm the community about a local lynching that seems like from the 1930s, are just a few of the real stories of real people in real situations. The stark black and white images provide an extremely intimate, humane and worthwhile view of human behavior under the stress of racism. Minervini hopes “it can facilitate a much-needed discussion on race and the current plight of African Americans who, now more than ever, are witnessing the intensification of hate crimes and discriminatory policies.” If you’re not African American, this captivating two-hour doc is about as close as you’ll get into Black culture without being part of it.

Prosecuting evil

The last surviving prosecutor at the 1945 Nuremberg Trials is now 98 years old and he tells his story like no one else can. In Prosecuting Evil: The Extraordinary World of Ben Ferentz, a meek, soft-spoken humanist lawyer begins his career working on one of history’s most important trials. He came face to face with men who on the surface might look like any ordinary military official or professional, but behind the masks represented the cruel, inhuman crimes of the Nazi regime. His slight demeanor belied his determination to bring these war criminals to justice. His lifelong campaign for peace and justice included a key role in the creation of the United Nations International Court of Justice in The Hague. Ferentz’s anti-war plea at end of the film is one of the most moving and memorable in recent film history. The TIFF program notes make a point about current culture that bestows fame and attention on white supremacists like Steve Bannon while ignoring the truly dedicated and extraordinary lives of activists like Ben Ferentz.

Anthropocene

You can say the name of this thought-provoking documentary, Anthropocene: The Human Epoch, by accenting any of the syllables. This is the third collaboration between committed filmmakers Jennifer Baichwal and Nicholas de Pencier and photographer Edward Burtynsky. Their other accomplishments addressing the same theme include Manufactured Landscapes and Watermarks, all focusing on changes in the world caused by industrialization and manufacturing. The stunning, sometimes slow motion or time-lapse visuals belie the manmade destruction caused to the planet depicted in marble quarries, tar pits, waste dumps and large factories, to name a few. The filmmakers traveled to six continents and 20 countries gathering over 500 hours of footage to make this timely wakeup call to humanity. The title and subject of the film refer to the geological time span that started with human presence on earth over 12,000 years ago, implying we are entering the final stage, termed the Great Acceleration, which started around 1945 with the speedup of socioeconomic and earth trends. The film has very little dialog; the visuals say it all. The music reinforces the profundity of earth’s change and its eventual demise in our epoch.

Unfortunately none of these films, as mentioned, addresses the destructive socioeconomic role of capitalism or the rampant rise of U.S. imperialism as earth’s resources are carelessly depleted for super-profits and countries are plundered and destroyed for money and power. Capitalist greed and the class struggle need to be addressed in films like these, to better explain the struggle for people’s democracy, and against racism, fascism and the destruction of our earth’s resources.