The morning before Thanksgiving, I woke up to an urgent message from someone back home in Arkansas. My name, employer information, and a link to my photo was just published on a neo-Nazi website. (!) Feeling more than a bit alarmed, I of course quickly checked it out.

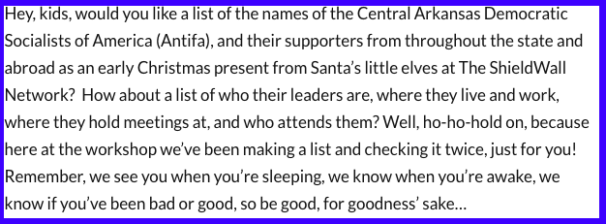

There, on the homepage of an outfit calling itself “The ShieldWall Network” was a list of dozens of alleged members of the “Central Arkansas Democratic Socialists of America (Antifa),” along with the places they worked—everything from Chipotle to universities to car washes to theological seminaries.

Now, I haven’t lived back in my home state for more than a decade and I’ve never been to a meeting of the Central Arkansas DSA, but I did recognize a good number of the names on the list. Old friends and acquaintances from anti-war groups and political campaigns I was a part of during my college days. Just a brief glance at the list and I knew I was in good company.

So what was the purpose of this list and why was ShieldWall—an organization that says it’s “open to all heterosexual Whites who support the idea of independent White ethnostates”—sharing it around on the internet?

The website’s administrator, Billy Roper, said he was offering the list as an “early Christmas present” to all his fellow white nationalists out there. Roper is a former Arkansas high school teacher and, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, a third-generation hard-core racist. He’s bounced around from one neo-Nazi outfit to another, apparently never having too much success in recruiting followers. His most recent public event brought out nine supporters for a protest near the Confederate monument outside the Walmart Museum in Bentonville, Arkansas back in March. To increase their influence, he’s encouraged members to “volunteer with your local Republican Party.”

What Roper and ShieldWall were up to with their list is a practice known as “doxxing,” sometimes spelled doxing. It’s the collection and publication online of detailed private information about a person or people (name, address, phone number, employer, relatives, finances, etc.) with nefarious intent. The term comes from the act of dropping documents, or “docs,” on a person. It’s a tactic that of course long predates the internet, but with the power of social media, such dossiers can spread far and wide very fast.

The goal of doxxing someone might range from prompting some low-level harassment to trying to get them fired from their job, or even go all the way up to enabling those who might commit violence against targeted people and their families or vandalize their property.

Legally, doxxing exists in a grey area, as your typical laws against harassment don’t cover activities like collecting and publishing publicly-available information online. Cyberbullying regulations haven’t caught up; they’re incomplete and in some places, non-existent. Until some violent act is committed, other means of prosecution are also pretty much closed. And even then, it might be difficult to charge a doxxer who didn’t actually carry out the violent act.

For progressive activists, journalists, professors, teachers, abortion doctors, and others—and for women members of these groups particularly—the threat of doxxing is an increasingly real one. It’s a time of intense polarization in the country. Trump’s racist, xenophobic, and misogynist rhetoric is mobilizing right-wing extremism. And with those kind of elements unleashed, one doesn’t even have to be doing anything too overtly political to become a target of death threats.

But it’s not just the neo-Nazis who are doing the doxxing. In fact, some of them are on the receiving end of it. Many are the cases of “alt right” personalities being outed as racist organizers and propagandists by their ideological opponents online.

The argument that vigilante-style doxxing (i.e. outside the channels of journalism and investigative research) can be an effective tactic against fascists and closeted white nationalists can sound like a convincing one. But as University of Maryland law professor Danielle Citron has said, it can also lead to “a downward spiral of depravity.” It’s equivalent to bypassing the law and taking it on yourself to inflict punishment.

The practice is meant to induce fear among those targeted, discourage them from being active politically, and expose them to possible retribution. That goal is the same whether it’s the right or the left doing the doxxing, and it’s dangerous.

Shine a light on the political activities of the leaders and public figures of far-right extremism by all means. That’s the job that journalists and academics have been doing for a very long time; it’s what the SPLC does.

But progressive activists, amateur sleuths, and moral crusaders should pause before they go spreading the home addresses, phone numbers, and emails of their adversaries online—especially when they risk identifying the wrong person and exposing them to danger.

Even if its consequences turn out to be rather benign, an act of doxxing is soft-core terrorism. At its worse, when a violent act actually results from it, the practice can be tantamount to accessory to assault or even murder.

If you find yourself on a list compiled by neo-Nazis or other unsavory elements or are already facing harassment online, check out the Speak Up & Stay Safe(r) guide from Feminist Frequency. Also helpful is the Anti-Doxing Guide for Activists Facing Attacks from the Alt-Right, produced by Equality Labs.

And if you find yourself tempted to expose your local Nazi’s personal info online, think twice. Report hate incidents and crimes to the authorities. Contact the Southern Poverty Law Center or the media. Don’t try to be a vigilante.