When it rains on downtown San Diego or its middle-class suburbs, the asphalt streets get shiny. The runoff is swiftly channeled down the storm drains, and spills out into the Pacific. On the hills of Tijuana, just a few miles south, rain creates a particularly sticky kind of mud called “barra.” Cars traveling down all the little dirt streets, where a million Tijuanecos live, are immobilized. If they start to move down a hill at all, even at a snail’s pace, they lose traction in the mud and slowly slide into another car, or a wall, or just a hole in the road. And there they sit until everything dries out again.

In this border city, the factories are like lords of the earth. They occupy the high points, the tops of the mesas, while the neighborhoods of the workers spread down the slopes into the valley below. When it rains, the tens of thousands of workers who pour into the maquiladoras every day begin their trip to work with a long trek through the mud to the nearest paved road for a bus, or an even longer walk all the way to the factory. Most workers don’t have cars anyway.

The difference between the one side of the border and the other is the difference between poverty and wealth. That differential inspired a building boom along the border, where 10 factories opened their doors each week during the first three months of the NAFTA era. Tijuana is the dark side of the Southern California economy, where much of the region’s industrial workforce lives on the south side of the border – the workers of the maquiladoras.

But companies aren’t the only ones moving across the border. As maquiladora workers have organized for better conditions, friends and allies have come from the north. In the world of NAFTA, a significant and growing number of unions and workers in both countries are beginning to build a network to confront their common corporate employers.

And of course, people – mostly worker and farmers – themselves move across the border by the million, in an enormous wave of migration. Migration has an economic function in a world capitalist economy, both in terms of the source and impact of the displacement in communities of origin, and the economic role and labor struggles of immigrant workers in the U.S.

Most mainstream coverage of Mexico focuses on the drug wars and the way the politics of the border play out in the U.S. The border is important, to be sure, but while the “hardening of the border” has an impact on people, the border region is a lot more complex. It is an arena of many social movements and struggles – maquila organizing, farm worker strikes, popular movements in border barrios, movements like the Frente Indigena de Organizaciones Binacionales. The border is more than a line people cross.

For the past quarter century NACLA Reports has published over a dozen articles examining displacement, migration, labor and the criminalization of migrants. They all add to a framework that sees this as a system, not just a set of policies. And they ask a question – “Who gains and who pays?” – that uncovers the rules of this system. To gain justice and human rights for migrants and working people those rules have to be changed.

In August, 2005, NACLA Reports published an account of the human cost of border economic development, and the price paid by workers for it, Stories from the Borderlands:

Tijuana’s oldest maquiladora closed last year.

It didn’t fall victim to the dreaded Chinese competition, confounding a wave of near-hysterical alarms in south-of-the-border newspapers, warning that the days of all Mexico’s factories were numbered. Instead, Industria Fronteriza owed its demise to a more prosaic cause: women stopped wearing nylons.

For almost four decades, seamstresses in this sprawling sweatshop churned out what was once the height of haut couture. Starting in the mid-1960s, the sleek hosiery caressing the slim legs stalking down New York’s fashion runways passed through the rough working hands of hundreds of Mexican women bent over machines on a sweaty, deafening factory floor within a stone’s throw of the U.S.-Mexico border.

Given changing styles, perhaps the company’s end could have been easily predicted. Plans might have been made for easing these veterans of needle and thread into jobs in some other border sweatshop. Or they might have been trained to fill one of the high-value-added positions that policy wonks insist should, and will, replace the old labor-intensive jobs that started the industrial gold rush here 40 years ago.

Traditional Mexican labor law would have helped the dislocation of these seamstresses. Since the 1930s, when radicals wrote the country’s labor legislation (and made it a model throughout Latin America), the Federal Labor Law has called for something U.S. workers would love to have: severance pay. A week’s pay for every year at the machine seemed only just to the reformers of that more egalitarian age.

For today’s seamstresses, a little money to pay for training programs, some severance pay to live on and a government interested in finding new jobs for older workers might have made quite a difference.

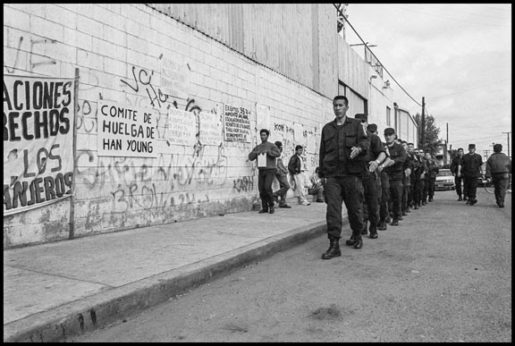

Not in the world of the border. This world turns labor law on its head—old post-revolutionary legal rights are just so much ink on paper, and even the decisions of federal judges to enforce the law are simply ignored.

Raúl Ramírez, Baja California’s Human Rights prosecutor, faults the government’s desire to protect investment above all else. “The authorities don’t care about the poverty of these communities, or their social problems like lack of housing or drug addiction. But they are very concerned with the question of the land titles of the large landholders. They want to take care of their investments. So the government uses the law, the police, even the army. They say this provides safety and stability for investors. And they abandon the poor.”

The social cost of this policy, Ramírez says, can be found in Baja California fields on any given day during the harvest season, when workers pick tomatoes and strawberries for U.S. supermarkets. Whole families work together in these agricultural maquiladoras—children alongside adults. Félix, a 12-year-old boy picking cilantro in Maneadero in June 2003, said his parents were making about 70 pesos a day (a little over $6), while he was bringing home half that. “We can’t live if we all don’t work,” he said, in the tone of someone explaining the obvious.

At wages a tenth of those paid for the same job in Los Angeles, it might seem fair if maquila workers only had to pay a tenth of L.A. prices for food, rent or any of the basic necessities of life. But that’s not the world of the border either. Two years ago a group of New England nuns, who organized the Center for Reflection, Education and Action (CREA), did an exhaustive survey of border prices. They found that for a kilo of rice, a Tijuana maquiladora worker had to labor for an hour and a half. Even an undocumented worker bussing dishes in Beverly Hills at minimum wage can take the same rice home with only 10 minutes’ pay.

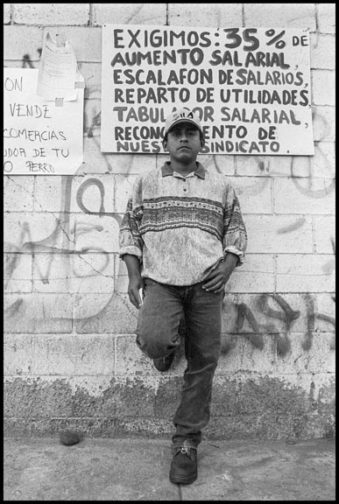

As usual, what appears to be a legal problem—in this case the enforcement of labor laws—is really about money. It’s a recipe for confrontation, and all along the border economic pressure is fueling a wave of industrial unrest.

In September 2008, as soon-to-be President Barack Obama promised voters that he would renegotiate NAFTA, NACLA Reports published Displaced People: NAFTA’s Most Important Product. It found that workers on both sides of the border suffered lost jobs, eroded rights and declining living standards in the wake of the treaty. Then it asked migrant rights activists what they saw as an alternative.

Since the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1993, the U.S. Congress has debated and passed several new bilateral trade agreements with Peru, Jordan and Chile, as well as the Central American Free Trade Agreement. Congressional debates over immigration policy have proceeded as though those trade agreements bore no relationship to the waves of displaced people migrating to the United States, looking for work. As Rufino Domínguez, former coordinator of the Indigenous Front of Binational Organizations (FIOB), points out, U.S. trade and immigration policy are part of a single system, and the negotiation of NAFTA was an important step in developing this system. “There are no jobs” in Mexico, he says, “and NAFTA drove the price of corn so low that it’s not economically possible to plant a crop anymore. We come to the United States to work because there’s no alternative.”

Economic crises provoked by NAFTA and other economic reforms are uprooting and displacing Mexicans in the country’s most remote areas. While California farmworkers 20 and 30 years ago came from parts of Mexico with larger Spanish-speaking populations, migrants today increasingly come from indigenous communities in states like Oaxaca, Chiapas, and Guerrero. Domínguez says there are about 500,000 indigenous people from Oaxaca living in the United States, 300,000 in California alone.

Meanwhile, a rising tide of anti-immigrant sentiment has demonized those migrants, leading to measures to deny them jobs, rights, or any pretense of equality with people living in the communities around them. Solutions to these dilemmas—from adopting rational and humane immigration policies to reducing the fear and hostility toward migrants—must begin with an examination of the way U.S. policies have both produced migration and criminalized migrants.

Trade negotiations and immigration policy were formally joined together when Congress passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) in 1986. While most attention has focused on its provisions for amnesty and employer sanctions, few have noted an important provision of the law: the establishment of the Commission for the Study of International Migration and Cooperative Economic Development, to study the causes of immigration to the United States. The commission was inactive until 1988, but began holding hearings when the U.S. and Canadian governments signed a bilateral free trade agreement. After Mexican president Carlos Salinas de Gortari made it plain he favored a similar agreement with Mexico, the commission made a report to the first president George Bush and to Congress in 1990. It found, unsurprisingly, that the main motivation for coming north was economic.

To slow or halt this flow, it recommended “promoting greater economic integration between the migrant sending countries and the United States through free trade.” It concluded that “the United States should expedite the development of a U.S.-Mexico free trade area and encourage its incorporation with Canada into a North American free trade area,” while warning that “it takes many years—even generations—for sustained growth to achieve the desired effect.”

The negotiations that led to NAFTA started within months of the report. As Congress debated the treaty, Salinas toured the United States, telling audiences unhappy at high levels of immigration that passing NAFTA would reduce it by increasing employment in Mexico. Back home, Salinas and other treaty proponents made the same argument. NAFTA, they claimed, would set Mexico on a course to become a first-world nation. “We did become part of the first world,” says Juan Manuel Sandoval, coordinator of the Permanent Seminar on Chicano and Border Studies at Mexico City’s National Institute of Anthropology and History: “the backyard.”

Contrary to NAFTA proponents’ predictions, the treaty became an important source of pressure on Mexicans to migrate. It forced yellow corn grown by Mexican farmers without subsidies to compete in Mexico’s own market with corn from huge U.S. producers, subsidized by the U.S. farm bill. Agricultural exports to Mexico grew at a meteoric rate during the NAFTA years, at a compound annual rate of 9.4%, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. By 2007, annual U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico stood at $12.7 billion. In January and February 2008, huge demonstrations in Mexico sought to block the implementation of the agreement’s final chapter, which lowered the tariff barriers on white corn and beans.

The root problem with migration in the global economy is that it’s forced migration. A coalition for reform should fight for the right of people to choose when and how to migrate, including the derecho de no migrar—the right not to migrate, given viable alternatives.

At the same time, migrants should have basic rights, regardless of immigration status. “Otherwise,” Domínguez says, “wages will be depressed in a race to the bottom, since if one employer has an advantage, others will seek the same thing.” To raise the low price of immigrant labor, immigrant workers have to be able to organize. Permanent legal status makes it easier and less risky to organize. Guest-worker programs, employer sanctions, enforcement, and raids make organizing much more difficult.

Corporations and those who benefit from current priorities might not support a more pro-migrant alternative, but millions of people would. Whether they live in Mexico or the United States, working people need the same things—secure jobs at a living wage, rights in their workplaces and communities, and the freedom to travel and seek a future for their families.

Finally, in April 2014, NACLA Reports published Immigrant Labor, Immigrant Rights. As Congress finally gave up trying to pass a comprehensive immigration reform bill, the article traced the genesis of the political coalition behind it, and unpacked the class forces at work. It concluded with the analysis put forward by the pioneering activists of the Oaxacan diaspora – that migrant rights includes both the human and labor rights of people as they migrate, and the right to stay home, for a future that can make migration a truly voluntary act rather than the product of the desperate need to survive.

In the late 1970s, Congress began to debate the bills that eventually resulted in the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) — still the touchstone for ongoing battles over immigration policy. The long congressional debate set in place the basic dividing line in the modern immigrant rights movement. IRCA contained three elements. It reinstituted a guest worker program by setting up the H2-A visa category; it penalized employers who hired undocumented workers and required them to check the immigration status of every worker; and it set up a one-time amnesty process for undocumented workers who were in the country before 1982. Guest workers (i.e. workers whose immigrant status was tied to temporary, specific jobs), employer sanctions and some form of legalization still occupy the main floor of the debate.

Once the bill had passed, many of the local organizations that had opposed it set up community-based coalitions to deal with the bill’s impact. In Los Angeles, with the country’s largest concentration of undocumented Mexican and Central American workers, pro-immigrant labor activists set up centers to help people apply for amnesty. That effort, together with earlier, mostly left-led campaigns to organize undocumented workers, built the base for the later upsurge of immigrant activism that changed the politics and labor movement of the city.

The critique shared by all these organizations is that the CIR framework ignores trade agreements like NAFTA and CAFTA, which have undercut workers bargaining power and employment opportunities in Mexico and Central America. Without changing U.S. trade policy and ending structural adjustment programs and neoliberal economic reforms, millions of displaced people will continue to migrate, no matter how many walls are built on the border.

Changing corporate trade policy and stopping neoliberal reforms is as central to immigration reform as gaining legal status for undocumented immigrants. There is a fundamental contradiction in the bipartisan policies in Congress that promote more free trade agreements, and then criminalize the migration of the people they displace. Instead, Congress could end the use of the free trade system as a mechanism for producing displaced workers. That would mean delinking immigration status and employment. If employers are allowed to recruit contract labor abroad, and those workers can only stay if they are continuously employed (the two essential characteristics of guest worker programs), then they will never have enforceable rights.

A new era of rights and equality for migrants doesn’t begin in Washington DC, any more than the civil rights movement did. Human rights reform is a product of the social movements of this country, especially of people on the bottom, outside the margins of power. A social movement made possible advances in 1965 that were called unrealistic and politically impossible a decade earlier. An immigration reform proposal based on human and labor rights may not be a viable one in a Congress dominated by Tea Party nativists and corporations seeking guest worker programs. But just as it took a civil rights movement to pass the Voting Rights Act, any basic change to establish the rights of immigrants will also require a social upheaval and a fundamental realignment of power.