The most successful social movements are highly organized, not spontaneous upsurges.

An inside look at the recent victory of hotel workers in San Francisco shows that a very democratic process, controlled by the workers themselves, was combined with multicity coordination to win substantial wage increases, workload reductions, and job protections.

Reflections from Anand Singh, president, UNITE HERE Local 2:

In my experience, when you articulate a vision to the members and challenge them, and you have a bold plan to win, the members will rise to the occasion. They will take the reins and run the union. That’s what happened in each of the cities where we struck [San Francisco, Oakland, San Jose, San Diego, Boston, Honolulu, Maui, and Detroit].

Early on we had a series of discussions among our members in Marriott hotels. It wasn’t just our most militant members. It was a cross section of our rank and file. People were working two and three jobs to make ends meet. There was this burning frustration and more than frustration – a real concern that they were just a paycheck away from being out on the street.

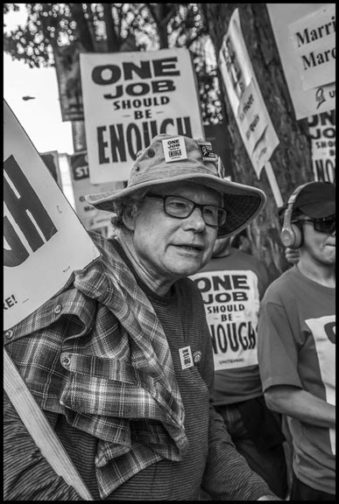

While the strike was a bold step, especially for folks who’d never done it before, we were just at a moment when the membership really was hungry for something. Not just for your run-of-the-mill kind of contract campaign, but aspirational demands like “One job should be enough!” [“One job should be enough!” was the slogan of the Marriott strike.] That reflected the experience they were living, and they really drove this fight.

The slogan and signs from the Memphis garbage strike [in Memphis in 1968, during which the Rev. Martin Luther King was assassinated] – “I am a man!” – were our inspiration. We wanted picket signs with the same handmade kind of feeling. And our message was developed right around the anniversary of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination and the events that happened in Memphis.

“I am a man!” really calls out the racism. “One job should be enough!” doesn’t necessarily do that on the surface. But when I see your photographs – our members holding those signs, out on the line, leading the chants – that’s exactly what it does.

This is a civil rights struggle. Our union is a union of immigrant workers, of people of color, working-class people. When you see them in those images, holding those signs, that’s what you see.

Our international union president, D. Taylor, said this should be a rallying cry for working people everywhere. The power of the message resonates with people who are speaking it on behalf of themselves, but also the public at large. It’s such a commonsense, modest demand. We need to continue raising it beyond 2018 and the Marriott campaign and our union.

Local 2 has a lot of history and a lot of strike experience, but that’s not true for all the hotels here that were in this strike. The St. Regis, the W, and the Courtyard never had a strike. At the Marquis, we had a limited two-day strike during the organizing – a majority strike but with a lot of folks who weren’t out. There were many cities in this campaign that had never struck.

We all relied on those of us who had experience. Some Local 2 leaders like Kevin O’Connor and Mike Casey had a lot of strike experience. [International Union President] D. Taylor in Las Vegas has been on picket lines in the center of many long strikes. And we also have rank-and-file leaders who have been out on strike. In San Francisco, we have the benefit of a great history, and their energy and expertise are translated across the city. It was always something we could rely on.

Our union historically has been a decentralized union. We have an international union [local unions like Local 2 belong to an overall union, called an international union because it includes local unions in Canada], but decisions are made local by local. Acting together was years in the making. Ultimately, that’s what won the strike. We took action collectively, across these cities in a militant fashion. I’m not sure the industry believed we’d do that.

In 2018, we were able to act in the way we did because of the campaigns that came before. I started at Local 2 in 2004 during the lockout [In 2004 San Francisco’s major hotels locked out their union workers for weeks, refusing to allow them to return to work]. The union’s central demand was a two-year term so we could line up with other cities. It’s been a long time coming. Each contract campaign set up the next. In 2018 we had multiple contracts expiring in multiple cities within a span of 12 months.

[By lining up the expiration dates of union contracts in different cities, the local UNITE HERE unions sought to create the possibility that they could strike at the same time when those contracts expired. They were able to strike Marriott Corporation in eight cities at the same time because their contracts with the corporation had all expired. In some cities, like San Jose, Oakland, San Diego, and Detroit, local unions had only one hotel under contract. In San Francisco, Boston and Hawaii, local unions had contracts covering multiple Marriott-operated hotels.]

Could it have been stronger? I think so. There are differences in what we’re fighting for from city to city. Certainly, Chicago had an expiration of 2018, but they had a different approach to the industry because Marriott wasn’t the dominant player there. Los Angeles is certainly engaged right now [Los Angeles was bargaining with Marriott at the time of the interview], but they had a much later expiration.

We’re getting better at it each time, learning how to work in coordination each time we go through this. I don’t look at 2018 as the seminal year. I look at it as a transitional year that sets us up for the next time around. I hope we’re stronger in 2022. What’s clear is that we’re much stronger acting together than we are acting alone. With the industry evolving and players like Marriott dominating it, all the more reason for us to make our plans and figure out ways to connect across cities.

Our strike was based on workers’ committees in the hotels taking responsibility, and being good communicators with workers, building a sense of accountability between the committees and the people they lead. We were really disciplined about our plan to build committees over the course of the past year. We were all approaching bargaining with similar demands, and we were ready to back those demands with action from our rank and file. Building a committee was the key to getting ready to strike. It gave each of the cities the confidence that we were all in this together, and we were looking at the same set of facts in each city.

When we launched the “One job should be enough!” buttons, our committee leaders went to the workers on their list, handed them a button and made sure they put it on. When we started doing public actions, they pulled people out to participate.

The committee person is the one who signs folks up and makes the reminder calls, and for the ones who don’t show, goes back to have a conversation with them. [A committee member will ask those workers] “What happened? I expected you to be there. This is our contract. We’re all in this together.” That got even more real the day after the strike vote. Then committee members tell workers in their hotel: “I’m walking out. I want you to walk out with me. I need you to sign up for your picketing shift.”

The strength and the conviction of the committee, going into a tough fight, is what everything is based on. In five of the seven San Francisco hotels nobody crossed the line, and in the other two, it was just one or two people. The history and experience of members who have been on strike certainly helped. But really, it was the level of detail in planning and building the organization that carried the day. There isn’t something special in the water in San Francisco or in these hotels. It’s the discipline and the meticulous committee building that got us through this.

Marriott was never dismissive of us. They are a behemoth corporation, and it would have been easy to brush us off. They never treated us like that. I think they had respect for what we’re capable of. And the closer we got to strike votes the more we saw things move in bargaining as we became more of a threat.

Then we walked out on strike. It forced a crisis for the company. I don’t think Marriott believed we could do what we did in all eight cities. It was a monumental task for the union, but it changed Marriott’s perspective on who we are. I do know that it had a major economic impact, some borne by the Marriott Corporation, and some by the owners of the hotels, probably the lion’s share. What they were losing in each of the hotels had an impact.

[In the US hotel industry, the hotel itself – the building and the property – usually belongs to an owner or group of investors. The owner then signs an agreement with a hotel corporation like Marriott to operate the hotel. The corporation then runs the hotel as part of its chain. It hires the workers, and where they have a union, negotiates a union contract that covers wages and working conditions. Sometimes the owners have a different set of interests than the corporation. In the case of the Marriott strike, according to Singh, owners may have lost more money than Marriott did, and been more anxious to settle it.]

This was the largest hotel strike we’ve ever carried out – eight cities, with the look and feel of a real national strike. The damage the company endured, day in and day out, as the strike wore on, really hurt their reputation. The hit they took on their name will have a lasting effect.

Cancellations happened in spades, and in all of the cities. Many groups and conventions pulled out. Things happened so fast it was hard to collect all those stories and recount them on the picket lines. Strikers live for that. Every day that an event cancels you want to announce it on the line because it means you won that day. Leading by example, the Shanti Project and the Chicana Latina Foundation cancellations at the beginning gave us something our customer campaign team could take to others. Guests walked out to the picket line and talk[ed] about what a disaster it was inside. That helped boost our spirits. They can’t run these hotels without us, and we have to remind them of that, day in and day out.

We had many unions honor our lines, either for the duration of the strike or right up until the moment their members would have lost their health coverage. And they were ready to come back out once they were eligible for their health care again.

The building trades didn’t cross our lines to go in and do renovations. That had an economic impact on hotel owners, who then leaned on Marriott to get the projects up and running. Teamsters would not pick up garbage or deliver. That all shows the labor movement is alive and vibrant – when people identify as union members, not crossing that picket line, thinking “those strikers are my brothers and sisters, even though they’re hotel workers and I drive a truck.”

There’s nothing better than having a member from another union walking the line with you. The drudgery of walking in a circle for hours and hours on end, for weeks and weeks, is difficult to maintain. The marches would lift people’s spirits right when things seemed to be dragging. And the food distribution by the labor council lifted people’s spirits too.

In the middle of all this, the workers at the JW Marriott [a non-union hotel in downtown San Francisco] sent a delegation to management and demanded a fair process for recognizing the union. We certainly believed that Marriott would go to the workers there, and at the non-union hotel at the airport, and point to the strike and say, “See, if you join the union this is what’s going to happen to you.” But our organizers had been talking to folks about the strike for months in advance. And the workers in those two hotels didn’t say, “I’m glad I don’t have to do that.” Instead many felt power themselves because of what the union workers were doing. It led to a sense of “I want to be a part of this,” because the strike was successful, and because the workers’ spirits on the lines were high.

Companies like Marriott underestimate our union and underestimate working people. People are willing to step up and do things at times when they seem almost impossible. Non-union workers are hungry for a voice. They want to be able to do the kinds of things the union workers demonstrated they could do with the union. Workers are hungry for a union that stands up and fights and wins.

So, our message to Marriott is, “We’re not going away.” We’re just not going to lay down. The strike lasted 61 days and we got a great contract. But our campaign with Marriott is not finished. One job should be enough for non-union workers and for union workers both.

This strike was very much a work in progress. It was the first time we had negotiations on a national basis in the hotel industry. We had to struggle with the process, of how to do this in the right way. We had guiding principles, at least for this campaign. First, there were common issues we wanted to take on – technology in the workplace, food and beverage service, the Green Choice program, sexual harassment and employee safety, and immigration. We knew these things would bind us together in national talks, so we focused on them.

[“Green Choice” is Marriott’s program for allowing customers to skip room cleaning for days at a time. The company makes extra profit because it doesn’t have to pay for workers to clean hotel rooms for days at a time. Workers object to this program because it is much more work to clean the rooms afterward.]

The second guiding principle was not to take the negotiations away from our members and rank and file leaders. In Local 2, given our history and our membership, that would be a recipe for disaster. Our rank and file would reject it. They would not stand for a contract negotiated outside of San Francisco without their input.

In each city, we maintained local bargaining over the wages, benefits and local issues, with committee and rank-and-file leaders actively engaged and at the bargaining table. On the national level, we’d reach agreement and bring it back to the committees. The president of each local went to national bargaining. We’d meet with the committees first, and talk through the initial proposals. Then, whether or not we had a tentative agreement or a counterproposal, we’d bring it back to our local bargaining committees.

Meetings in Las Vegas started prior to the strike, and then there were several sessions during the strike. It was a complicated process. We know we have more collective power when we bargain together, but we want to balance that with staying close to our roots. We know our power is in our rank-and-file leaders.

We’re just trying to work our way through this, the first time a sizable collection of locals bargained together with the world’s biggest hotel corporation. We achieved some very meaningful results. But UNITE HERE is a decentralized union. Local 2 takes pride in our independence and who we are.

I’d like to believe we built something this time around and showed we had success working together. The lesson I take from it is that, as difficult as it may be, with different locals and leaders (and we’re all very opinionated people), we were all in a room together and went through a campaign together, and then we all walked out on strike together. And we all came out of it on the other end a lot stronger. How do we not replicate this, but build on top of it? How do we grow it to more cities? How do we take the next step in national bargaining, so that we have more common issues we’re fighting for?

Now we’re going to go to the other hotel chains in San Francisco, and [tell] them that they have to accept what we negotiated with Marriott. Marriott [overshadows] the others, but Hilton, Hyatt, Intercontinental are all waiting in the wings. Several other UNITE HERE locals have contracts expiring with Hilton, so we have to challenge Hilton to do right by their workers. I’m sure these other hotels are studying the terms of this deal. Can’t imagine they’re too happy about it.

I keep thinking about what the strikers did for 61 days. I remember right before Thanksgiving, Marriott moved maybe an inch in bargaining. I wondered what this was going to do out on the picket lines. Strikes really are won a day at a time. So I walked out to the lines and the leaders were talking about what happened in bargaining, and how insulting Marriott’s offer was, and how it made them feel. Maybe the company thought that would be enough to make people go back to work. But they underestimated their own workers.

People rose to the occasion, running the lines strong when the downpour started, through Thanksgiving and into the holidays. After Thanksgiving they started putting up Christmas lights and decorations on the picket line tents. When we went into that final round of bargaining, we knew we were going to be fine.

The Saint Francis and the Palace and the Union Square Hotels have done this before. But at the hotels that had never gone on strike, and who were doing it for the first time, it was really moving to see people go through this experience together. People came together in a way they never had before. People who’d worked together for 15 or 20 years. It was one of the most moving and transformational experiences, one that only a strike can bring.

Reflections from Kevin O’Connor, organizer for UNITE HERE Local 2 and Marriott campaign coordinator:

We won because there were a lot of workers on strike. That was the base everything else was built on. I don’t know what Marriott expected. There were lots of places on strike, many of which had no history of strikes before. I think Marriott wondered whether it would happen at all.

National bargaining is the collective idea, that we can get things that we can’t otherwise. We got an agreement on technology, for instance, that was better than any local could reach. This was the first time we’ve had multicity bargaining in our union.

Our message, “One job should be enough!” affected how people saw Marriott. Once we were on strike we did lots of outreach to customers. The customer campaign is a strategy we pioneered here in San Francisco and is now built into the way the union conducts strikes.

To understand how we got to national bargaining we have to go back in history to 2001-2002 when the union first began talking about lining up cities. Chicago and Hawaii began to line up their contracts to expire in 2006. At that time the industry wasn’t paying much attention to us.

Then in 2004, San Francisco had contracts expiring, and the union wanted a two-year agreement. The industry realized the danger [to the hotel corporations of increased union strength] and refused to agree in San Francisco. We went on strike in four hotels, of what was then the multi-employer group. All the big hotels belonged to this group. We were eventually going to pull the rest of the 14 hotels in the group on strike too, when they did our work for us by locking us out – 4500 workers were on strike or locked out.

We had a 53-day strike and lockout, and at the end, the hotels were forced to let us come back to work. We worked for two years without a contract because they wouldn’t agree to the expiration date. They stopped collecting dues, and so we had to collect them ourselves. But our members stepped up because they knew why we were fighting.

In September of 2006, we took another strike vote, and they did in Chicago and Hawaii also. The hotels then settled in all three cities. That’s how Local 2 got on the same timeline [of common contract expiration dates] with Chicago and Hawaii.

There were more fights, all about staying on track. Hyatt workers in San Francisco went without a contract for three years, and Hyatt became the first multiple-city campaign. Hyatt and Hilton were our main targets historically, with Marriott in the background. But by 2017, most cities no longer had multi-employer groups. Meanwhile, Marriott bought Starwood [a corporation that operated some of San Francisco’s largest union hotels], where we had important contracts, and we had to change focus. In San Francisco we then had seven Marriott hotels with contracts, Hawaii had five and Boston had eight. We could all see 2018 coming at us, so we had to really organize.

The purpose of organizing was to run a hotel strike. We weren’t running away from a strike but running toward one. So preparation started in 2017, a year ahead, with an eye toward building committees in all of those hotels. We had to figure out how to work together. We needed an aspirational approach to our demands – real economic improvements and job security.

In Local 2’s analysis, we have certain advantages in the hotel industry. The hotels can’t close and run away. The nature of the work is another. In the service industry, the money [that is, the customer] walks in and out the front door every day. This is especially obvious at a hotel like the Saint Regis, which charges hundreds of dollars a night. The disruption of a strike is not what they’re selling. So we can get to the core of their business in a consumer-driven industry.

We had to learn how to do this over the years [disrupt operations and reach out to customers], and defend our right to do it. Our first campaign like that, at the Parc 55, went on for three and a half years. The key to it is lots of people on the picket line. Our picket lines make a lot of noise, but noise itself is a two-edged sword. When picketers are drumming in rhythm it unites them, especially when people are chanting together at the same time. But we actually had to scale back the drumming this time in order not to lose public sympathy, especially the support of the workers in the area who were being driven crazy by the noise, day after day.

We discovered we need two factors to run successful picket lines, and we’ve been very aggressive in court fights to defend them, starting with the 1980 strikes in the hotels and restaurants. We were enjoined [by court orders] in all those strikes and we fought those injunctions. We have to defend our right to be out there in large numbers, and we have to defend our right to talk with the public. We’ve fought hard enough so that this time the company never tried to get an injunction against us. We’ve kept the ability to talk to the guests as they go in and out, and we use it.

Those picket lines are the heart of the strike. They are very participatory. We had 570 strikers at the Saint Francis – no one crossed the line. And almost all picketed.

The real work is building the union committee in each hotel, and relying on the workers. That happens at a natural pace. At first, we organize people around the proposals we want to make in bargaining. Then we have a big strike vote, with big majorities. This time we had over 95 percent voting for the strike in every city. But what happens then is really the most important moment in building the committee on the shop floor. They go back into the hotel and sign people up for picket duty. This is the union acting like a union.

There are very charged discussions when they do this. They have to tell worried people that everybody has bills. But they never yell at people or threaten them, because we won’t give anyone an excuse to do the wrong thing – that is, not walk out when the time comes. Sometimes it’s hard to convince the committee that nobody is a scab until they actually go to work instead of striking.

The strike organizes people. A strike is our weapon and our power. We use the strike when and how we choose. Getting people out on strike is the work of the committee. They have to convince everyone that they’re accountable to their coworkers. We never give up on people, because that just gives them an excuse to betray everyone else.

Getting our locals together meant getting a commitment from each city to run good strikes. If we do that right, then our members will be willing. The heart of that commitment is the picket line signup. That means we will go person by person in every hotel. We will know how each person thinks, and we will convince each person. The committee won’t accept “I don’t know” as an answer.

All eight striking locals adopted this, along with the “One job is enough!” idea. It’s very flexible and basically means economic fairness. It’s saying we want a big step up, not 25¢. But we also need job security: What good is money if we lose our jobs? So the slogan works on two levels. For one group of workers, it’s about stopping the hotel from combining jobs, getting rid of some people while overworking others. For another group, it means not having to work two or three jobs to survive. To the public, it means saying that Marriott can afford to do this – that they’re not some mom-and-pop company.

The contracts started expiring in February, and in some cases, we had to delay the strike votes because we hadn’t done enough bargaining. We finally took all the votes from September 10-18, and as a result, we all went on strike within six days of each other. Every city was driving the same program, but every city struck when it was ready.

In Las Vegas, we had national bargaining on issues like technology, and then each city settled its own economic issues. The economics in every city are very different. We told Marriott they had to settle the cities first that had only Marriott hotels because the cities with multiple hotels had the most bargaining leverage. We couldn’t leave the smaller cities hanging out without a contract there once the others had settled.

I knew we were on the right track when we had 23 hotels on strike in eight cities, and the strike vote came up in Seattle. They got a good contract without striking and were the first of the “One job should be enough!” cities to settle. Marriott didn’t want 24 hotels on strike in nine cities.

The article above appeared previously in Truthout.