On the show This Is Me Now, comedian Jim Jefferies recently joked that Canada should build a three-foot wall on its border to prevent “Americans [who] are crawling over because their lungs are filled with coal from getting all their jobs back.” This joke clearly pokes fun at the U.S. immigration debate and the risks of industrial work, yet it also betrays a sneering elitism about deindustrialization and displaced workers. Middle-class and elite observers with no roots or interest in working-class activism often adopt a paternalistic attitude—“if only these silly workers would accept that times have changed”—and accuse workers of being rendered stupid by smokestack nostalgia that idealizes the good times and erases the bad.

The toxic combination of neoliberalism and deindustrialization has devastated working-class communities, organizations, and cultures. Statistics from communities that once relied on a single industry speak for themselves, coldly recording increased crime, poverty, and ill-health as the social fabric unravels. Yet statistics cannot capture the emotional narratives of deindustrialization.

To capture that, we need to talk with the people who have lived it, as I have done with former Scottish steelworkers. Listening to the voices of workers reveals the complex experience of job loss and economic restructuring.

Steelmaking is a dirty job, performed under intense heat and exceptional danger. Harmful gasses and dust destroy workers’ health, and horrific accidents cripple their bodies. Steelworkers know this all too well. As former steelworker Brian Cunningham put it, a typical day could switch from “mundane, repetitive, monotonous, to absolute terror… When it went wrong, it went spectacularly wrong.” Peter Hamill recalled how a fellow steelworker “had been feeding a rope in and it had whiplashed him, cut him, killed him.” Death was a persistent reality for steelworkers. Tommy Johnston’s “lowest point” was witnessing a co-worker “strangled in a conveyor belt.”

In light of such stories, we might expect workers to be glad to see steelworks close. But they aren’t. Instead, they say they would not have left if given the choice. As Johnston said, he would “go back tomorrow” if he could. Why?

These workers are not deluded by rose-tinted nostalgia; they simply recognize that the jobs they have now don’t offer the real, tangible benefits of industrial work. Following a path common to other displaced industrial workers, the former steelworkers I interviewed found new jobs as production line workers, taxi drivers, cleaners, or janitorial staff. Most of these jobs are insecure and low-paid.

For James Carlin there was “absolutely no comparison whatsoever”—his wage more than halved in his first new job. Likewise, Cunningham’s annual salary diminished from £24,000 to £10,000 Finding it “hard to say,” Johnston admitted that after twenty-five years his annual wage is now just below his steelworker wage of 1991 in absolute terms.

It wasn’t just that wages are considerably lower. Workers also lost access to monthly bonuses, union-negotiated wage rises, and seniority-based promotion. Instead of improving their standard of living, these former steelworkers had to cut household spending and sacrifice hobbies, social outings, and family holidays. Some sold their cars and even forfeited ownership of their homes.

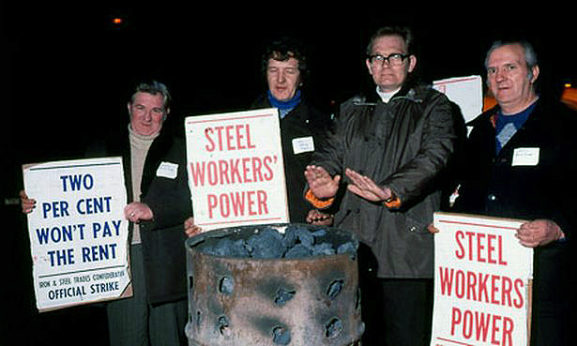

But even more than the economic loss, these workers mourn the loss of a powerful and vocal union and the workplace culture it fostered. Cunningham described labor relations in his former workplace as “respectful;” the authority of the union “always put the management on notice.” In stark contrast, his new management was aggressively anti-union: “If you joined a union you were sacked, you were out the door.” Carlin observed workforce bullying and harassment by an “almost dictatorial” management which actively suppressed union organizing by outright dismissal.

Not blinded by nostalgia, workers were in fact well aware that the culture of workforce/management “mutual respect” was not underpinned by benevolence, but rather necessity, as workers’ treatment corresponds to their respective power in the workplace. By contrast, Carlin summed up his later non-union workplace by observing: “we never had any power, we never had any voice.” The heavy unionization of the workplace encouraged a culture of solidarity and cooperation.

Indeed, steelworkers felt part of a cohesive occupational community—“a part of something”—and took pride in a culture of camaraderie where workers “looked after each other.” The workplace was embedded in community life through a plethora of trade union and steelworker voluntary associations, sporting teams, charity initiatives, educational programs, hobby clubs, and political groups. Cunningham extolled the variety of social opportunities: “The social side of it was terrific… we used to do overnight stays, dinner dances, we used to do mid-week breaks for the golf… you had your anniversaries, weddings, engagements, so the social side of it was really good.”

Regular socializing fortified a sense of community among steelworkers, as Ian Harris described: “You got invited to everything, you were at the fishing club dance, the bowling club dance—I was in the golf club so I was at the golf club dance, the football dance, everything.” Workers’ social life was intrinsically linked to their workplace, and this high degree of social embeddedness fostered an intense sense of communal identity, as Frank Roy commented: “It was your identity.”

The material basis of the working-class culture was demolished alongside the steelworks. The absence of the workplace community organizations and social events meant that post-layoff employment lacked the interwoven social aspect and dynamic culture of solidarity which had defined steelmaking. In his new job, Carlin lamented, “there was no camaraderie, there was no team aspect to it, you were an individual and you stayed an individual till the day you went home.”

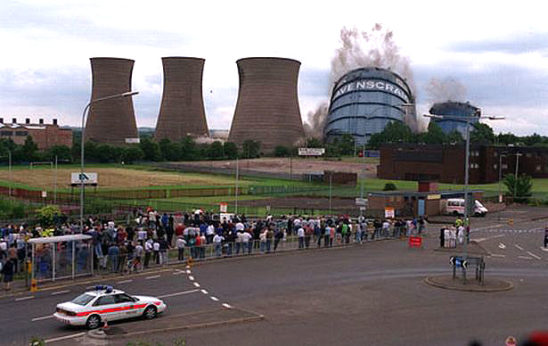

Family histories of steelmaking had encouraged even greater bonds among workers, blurring the lines between workplace and family. Ravenscraig steelworker Tommy Brennan felt like he belonged in the mill: “I worked in the Craig, my brother worked in the Craig, my two sons worked in the Craig, my brother’s three sons worked in the Craig.” Also from a family of steelworkers, Carlin saw steelmaking as his natural “progression” after school; it was part of his heritage, a gateway into the labour movement, and central to his working-class identity. The closure of the steelworks ruptured this identity, provoking a sense of placelessness: “I just couldn’t settle, I couldn’t settle, you know what I mean, it was always in my head about the steelworks.”

The closure of the steelworks disconnected workers from one another, bringing an end to decades-long workplace relationships. Jim McKeown described losing a part of himself, a feeling he believed was even more pronounced among the older generation: “There was bit of me missing, because a lot of those people, even though they are living round about, I’ve never seen them again… I think a lot of the older ones… a part of their soul was missing.”

Frank Shannon, who was part of this older generation of steelworkers, agreed, stating that many lost their sense of purpose and found their lives defined by loneliness: “I know a lot [of] people that didn’t last a year, dead… maybe drink, gambling… work was their life… it was devastating.” Deindustrialization fundamentally shattered occupational communities, rupturing workers’ social lives and bringing an abrupt end to their communal work environment, leaving in its wake social isolation, bitterness, and alienation.

We should, of course, avoid simplistic nostalgia for industrial work, and we should not forget its dangers and adverse health effects. Yet workers are right to remember and value many aspects of industrial employment. The high pay delivered steady social mobility, the work itself fostered a sense of occupational pride and identity, and powerful trade unions provided a culture of solidarity which allowed workers to advance their rights.

Working-class jobs have now become endemically low-paid, exploitative, and insecure. Decades of neoliberalism have crippled the labor movement, delegitimized working-class history, and all but erased working-class collective memory. Most young workers now know nothing else but low paid precarious work. For them, that is the norm.

Memory of and even nostalgia for the rights once held by industrial workers, despite the risks and exploitation, reminds us of what can be achieved by workers when they have strong unions and working-class communities. Those who dismiss workers’ positive reflections of heavy industry as little more than rose-tinted nostalgia are, purposefully or not, undermining a legitimate class memory of powerful workers and stable communities. In the process, they also undermine the potential organizing power of today’s working class.

This article originally appeared at the Working-Class Perspectives site, hosted by Georgetown University’s Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor.