The Communist Party was founded in the middle of a year of intense militant workers struggle. From coast to coast and among workers in a wide variety of industries, the U.S. working class stood up for its rights and for the dignity of labor. It was met at every step by the forces of capital, be it court orders or the armed might of the police and/or the military. Some workers won victories, but often repression brought about defeat. The flame of righteous struggle, however, could never be extinguished. This essay, the final of a 3-part series, highlights the bravery of coal miners, the workers of Seattle, and steelworkers. Read Part 1 and Part 2.

Coal mining is one of the most dangerous occupations in society. The physical labor of extracting the mineral is exacerbated by the ever-present danger of a cave-in. In its early days, coal mining was a small-time operation, with many mines being surface operations. It was not unusual for the mine owner to work beside his employees.

As the industry grew, however, it became much more capital intensive, and most mines were opened underground. The major centers of coal mining developed in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, Illinois, and Wyoming.

Employer-worker relations deteriorated as workers asked for safer conditions, better pay, and shorter hours. Strikes became a common feature of the industry. The major union, the United Mine Workers (UMW) was established in 1890. One characteristic of the UMW’s history was a struggle between a militant, often locally-centered rank-and-file and a more “business union”-oriented hierarchy. That was much in evidence in 1919.

During World War I, the coal industry was regulated under what was known as the Washington Agreement. As with the general employer-labor situation at the time, the coal owners made concessions to the union, but forbade strikes.

2019 marks a century since the founding of the Communist Party USA. To commemorate the anniversary of the oldest socialist organization in the United States, People’s World has launched the article series: 100 Years of the Communist Party USA. Read the other articles published in the series and check out the guidelines about how to submit your own contribution.

Miners in the region around Belleville, Ill., ignored these restrictions and, in July 1919, went on strike primarily to end the wartime restrictions and for a new contract, centered on the demand for higher pay.

Over the next several weeks, workers elsewhere, spurred on by a combination of poor economic conditions and in solidarity with their Belleville brethren, went on strike. On Nov. 1, the national office of the UMW called a national strike which, at its height, saw 425,000 miners stopping work.

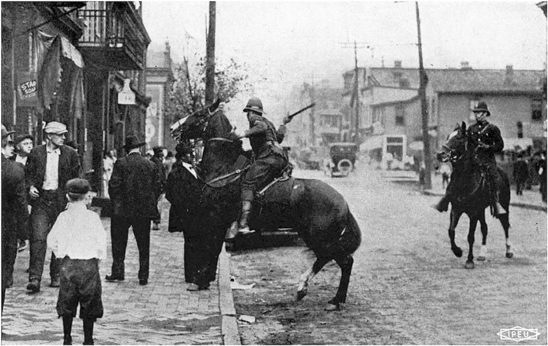

Almost immediately, the federal government responded, both through the courts and with armed force. On the one hand it sought an injunction, on the other it ordered federal troops into the coal fields in Utah, Washington, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Pennsylvania. The union leadership capitulated and the strike came to an end. The rank-and-file, however, did not go quietly. Over the next three years, militants struggled against the unholy alliance of the employers, the government, and their union leadership.

The Seattle General Strike

Seattle has had a long tradition of dynamic labor organizing. With the opening of the northwestern quadrant of the United States at the end of the nineteenth century, it emerged as the economic center of the mining, timber, shipping, and railroad industries.

Industrial conditions were unsettled, with an aggressive employer class that sought to keep wages low and profits high, and who worked to keep out any type of workers’ organization. They drew their workforce from the many migratory workers available and used any method to keep them divided and powerless.

The workers, however, refused to accept their lot. They began to speak with a militancy that demanded major changes in the established order. To achieve success, they found the craft orientation of the American Federation of Labor too restrictive and sought to create industrial unions.

Among the organizations they turned to was the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), which advocated “One Big Union”—a union of all workers. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, the IWW gained a strong presence throughout the region, particularly among miners, lumber workers, and railroad workers.

After World War I, shipyard workers sought higher wages from the federal government, which oversaw the construction of vessels, and on Jan. 21, 1919, 35,000 unionists went on strike. Their action proved to be a catalyst to other unions in the city, and two weeks later, on Feb. 6, over 25,000 others, including 101 AFL locals, joined them in the first general strike of the new century.

In the words of one account:

“[M]ost of the remaining work force stayed home as stores closed and streetcars stopped running. The city was stunned and quiet. While the mayor and business leaders huddled at City Hall, eight blocks away, the four-story Labor Temple, headquarters for the Central Labor Council and 60,000 union members, hummed with activity. An elected Strike Committee had taken responsibility for coordinating essential services. Thousands were fed each day at impromptu dining stations staffed by members of the culinary unions. The Teamsters union saw to it that supplies reached the hospitals, that milk and food deliveries continued. An unarmed force of labor’s ‘War Veteran Guards’ patrolled the streets, urging calm, urging strikers to stay at home.”

As one striker remembered years later, “Nothing moved but the tide.” Newspapers around the country stoked fears of an imminent “Red Revolution.”

The city government, backed by state and federal authorities, moved swiftly to end the strike. Many leading workers were arrested and the federal government refused to negotiate. As a result, some of the unions got cold feet and told their members to go back to work. Six days after it began, the Central Labor Council called off the strike. Mayor Ole Hanson of Seattle said that “Americanism” had beaten “Bolshevism.”

There was no violence reported during the walkout. Though unsuccessful at the time, the Seattle General Strike proved to be an inspiration to generations of workers to come.

What means a strike in steel?

From its earliest days, industrial relations in the steel industry could be described as bitter and bloody. Emerging in the years around the Civil War, the growth of steel production was boosted by newly-developed rich iron ore deposits around Lake Superior and coal fields in Pennsylvania and West Virginia. Add in a plentiful and highly developed water transportation system and by the late nineteenth century, steel had grown into a dominant part of the U.S. economy.

Working in a steel mill, however, was arduous and often dangerous. The workday was usually twelve hours and many of those employed worked seven days a week, more than seventy hours. It was not uncommon for accidents to happen, especially gruesome around molten metal.

Life beyond the factory was dominated by the steel corporations. They controlled political power in many of the mill towns. They denied workers the right to hold meetings. Social institutions, particularly the churches, supported the corporations. Ministers and priests denounced outside “agitators” and worked to keep the rank-and-file under control. Employers exploited to their advantage differences between skilled and unskilled workers, and native-born and immigrants, mostly from central and eastern Europe.

At times, however, the workers overcame these obstacles and united to fight for their rights. Most notable was the Homestead (Pennsylvania) Strike of 1892 when the workers at the Carnegie Steel Plant rose up to fight a 20% pay cut. The strike turned bloody when the steelworkers repelled an attack by Pinkerton agents. Seven workers (or supporters) were killed. A combination of factors led to a total defeat of the union, however. Conditions remained deplorable.

During World War I, the need for the steel industry to keep producing for the war effort and to prevent strikes led the War Labor Board to allow union organizing and an improvement in wages and hours. In the months after the Armistice, however, the steel companies reverted to the pre-war working conditions. But the workers would not quietly accept them.

Anger among the rank-and-file became palpable; they wanted to keep the improvements they recently experienced, not a return to the tyranny of the past. In addition, growing inflation and stagnant wages made living more difficult. Something had to be done, and the only way to effectively fight for change was to unionize.

The problem was that the steel industry was made up of many different craft skills. The major union, the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers—the Amalgamated Association—was a craft union affiliated with the AFL.

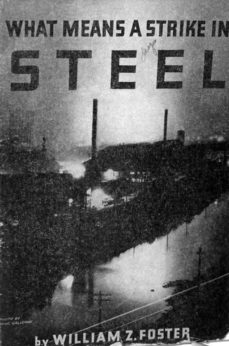

Seeing an opportunity to organize the steel workers, the AFL set up a national committee composed of twenty-four unions representing the vast array of different workers in the industry. Its leader was a highly skilled trade union organizer who had also been instrumental in organizing Chicago’s packinghouse workers—William Z. Foster.

The child of an Irish immigrant father and an English-born mother, he left school at the age of 10. He worked at many different jobs—at a fertilizer plant, as a railroad construction worker, and a streetcar motorman in New York City, among many others. He joined the Socialist Party but left it for the more militant IWW. He had a varied career in politics, but his focus was always on organizing workers and fighting for their rights.

By the summer of 1919, steelworkers grew increasingly militant. One observer told the committee, “All over the steel district the men are in a state of great unrest….” The two main centers of the steel industry, the first being the area encompassing Chicago and Gary, Ind. And the second being Pittsburgh, were ready to strike.

On Sept. 22, the workers went on strike. At its height, more than 350,000 walked out as part of the strike. Plants across the country were idled, a powerful beginning to what became a protracted struggle.

The federal and various state governments, responded in several ways. They painted the workers as dangerous radicals and used injunctions to break the strike. In addition, there was growing bickering among the unions in the national committee which weakened the movement and eventually led to the strike’s end.

Many workers were forced back to work because they needed to provide for their families, particularly with the approach of winter. In Jan. 1920, the committee called off the strike; it was a bitter defeat for the workers.

The battle lines for the next decade were drawn. As the 1920s dawned, the federal government, led by Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, began a concentrated effort to round up suspected radicals, those whom he called “subversives,” and deported many of the foreign-born among them.

Revolutionary organizations, including the newly-formed Communist Party, were forced “underground.” This was the “Red Scare” of 1919-20. Employers went on a major anti-union offensive, the “open shop movement,” aimed at destroying the labor movement. Within ten years, many unions were reduced to a shell of their former selves.

Within two years of the end of the Great Steel Strike, William Z. Foster joined the Communist Party of America (later to become the Communist Party USA) and became one of its leaders. He would remain one of the foremost personalities in the party for the next three decades. Foster and the Communist Party would be there during the great struggles that saw the birth of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in the 1930s and the struggle against fascism during World War II.

The legacy of the militant workers of 1919, be they garment workers, miners, actors, the police, steelworkers, or one of many other occupations, is one that lives with us today. Times may have changed, but the struggle goes on.