WASHINGTON—Is the General Strike, a worker weapon that struck fear into corporate chieftains and crooks and their political cronies a century ago, making a comeback?

A new film, commemorating centennial of the Great Seattle General Strike of 1919, plus a panel of experts in worker history and rights, tackled that question Feb. 6 at a pro-worker, pro-minority, pro-woman D.C. bookstore.

The answer: Yes, but in a different way than it was practiced in the decades before Seattle. And on a different scale.

The Pacific Northwest Labor Heritage foundation, with both financial and archival aid from Oregon and Washington state labor historians and unions, produced the film, The General Strike: Back To The Future?

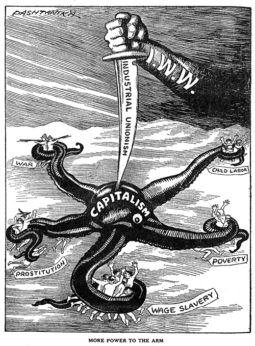

It traced the area’s crowded and militant labor history, as workers—many of them organized by the Industrial Workers of the World—battled inhumane conditions, corporate hatred, complicit politicians, and schemes to divide and conquer workers by race, class, and sex.

“The IWW had the principle of overthrowing capitalism in favor of syndicalism or socialism,” the film said. “Its constitution said, ‘The working class and the employing class have nothing in common.’”

The apex of the movement was the six-day general strike which shut down Seattle in 1919. It started when 3,500 shipyard workers, angry at corporate reneging on World War I-era promises of post-war union recognition, pay raises ,and better working conditions, walked off the job.

Those workers and their IWW leaders laid their community groundwork well, going to the area’s Central Labor Council for support and finding one lone pro-worker newspaper to trumpet their cause. More than 110 other union locals joined them, and their workers walked, too. And they also spread the word: No violence. Don’t even go on the streets, organizers often added.

The result: 65,000 workers—everyone from carpenters to lumberjacks to railroad workers to female household workers—walked out. Race didn’t matter, sex didn’t matter. They all struck.

Seattle ground to a halt, attracting worldwide attention. But Seattle’s strike ended after some union locals defected and sent their members back three or four days in, but union leaders considered it a win. And there were other citywide strikes afterwards, notably in Centralia, Wash., Portland, Ore., and Winnipeg, Manitoba in Canada.

Since then, general strikes have been infrequent, and at least one, by hundreds of thousands of steelworkers, before the formation of the United Steelworkers in the 1930s, was crushed, also in 1919. It took almost two decades, though the film didn’t say so, for steelworkers to organize in the USW, with financial and logistical direction from the United Mine Workers.

Other later, though infrequent, general strikes, in the Twin Cities and San Francisco in 1934, in Rochester, N.Y., in 1946, by the Steelworkers in 1959, and by all of the nation’s postal workers in 1970, succeeded in their goals: Union recognition, enactment of the National Labor Relations Act, decent pay and working conditions (USW) and living wages, and better working conditions and union recognition for the postal workers, many of whom had to depend on public assistance.

Mass arrests, police raids on union offices, and trials “which turned into circuses” symbolized corporate and government reaction. They included trial of 11 of the Seattle strike “leaders” in 1919, with eight convictions, Calvin Coolidge’s breaking of the Boston police strike, and the Wilson administration’s infamous “Palmer Raids.”

Bosses and politicians tarred workers as “Reds” and the raids led to thousands of arrests and hundreds of unjustified trials and deportations of so-called “radicals.”

Later government action was important, too. One panelist, American Prospect senior editor Harold Meyerson, pointed out the most important action when Minneapolis and San Francisco workers were forced to strike in 1934 was “FDR did not send in the National Guard. It was the most radical thing he did—nothing.”

Minnesota Gov. Floyd Olson also refused to send troops, despite demands by a cabal of Twin Cities corporate moguls. And Congress passed and FDR signed the National Labor Relations Act in 1935.

That’s unlike conservative Democratic President Grover Cleveland during the 1893 nationwide Pullman general strike, though the film did not cover that. Over the protests of progressive Illinois Gov. John Peter Altgeld (D), Cleveland sent troops to break the American Railway Union’s walkout over Pullman’s unilateral decision to cut pay by almost half, without cutting prices and rents in his company town. Cleveland later prosecuted strike leader Eugene V. Debs.

It’s also unlike the actions of recent Republican-run administrations. Ronald Reagan’s 1981 firing of all the Professional Air Traffic Controllers who had to strike over workplace safety issues gave corporate chieftains a “green light” to try to wreck unions, break strikes, and reduce workers’ living standards.

After that, the number of traditional strikes dropped precipitously. The anti-worker onslaught that followed was so huge that—though the film didn’t say so—Pacific Coast port owners considered asking GOP President George W. Bush to send in troops to run the ports when negotiations broke down with longshore unions just over a decade ago. Bush didn’t do that, but got a court order against the union, sending the workers back on the job. And recent data show employer lockouts of workers have been double the number of strikes.

But the panel, of labor historian Joe McCartin, University of Maryland professor Julie Greene, and Meyerson, said the tide may be turning again. They considered why.

One reason, Meyerson pointed out, is that support for workers’ rights and unions is at an all-time high, with public opinion polls showing 62 percent favorability. It’s even higher among younger and millennial workers. The catch is that workers don’t act unless conditions are “right.” And many younger workers have little sense of labor history—a gap the film helps hope to correct.

So workers are trying to make conditions right, the panelists noted. The general strikes these days have different tactics, aims, beginnings—from the bottom up, not the top down—and, most importantly, wide community support, they said. Those factors are tied together.

The three cited the 2012 Chicago teachers strike, the statewide teachers’ strikes last year in Kentucky, Oklahoma, Arizona and, most importantly, West Virginia, the recent and successful Los Angeles teachers strike, and the one-day strikes staged by the Fight for $15 And A Union movement of fast-food, retail, warehouse, and other underpaid, exploited workers.

All those general strikes, especially the West Virginia one, which shut down every public school in the state, had several elements in common, the panelists noted. Rank and file fed-up workers started them, with union leaders often scrambling to catch up.

The workers were forced to strike against corporate chieftains or—most often—public bodies not for pay and benefits, but for community causes, such as living wages (the fast food workers) or decent funding for school buildings, books, and, in L.A., staffing.

Meyerson pointed out another big difference: Acceptance of the basic capitalist structure. One 1946 strike, by the Auto Workers against GM, had changing corporate governance to enhance worker power as a goal. That goal failed. The strike didn’t: It brought workers better wages, pensions, and health care.

And, McCartin said, workers forced to strike now lay the groundwork for wide community support by emphasizing the community-oriented goals. That’s why teachers drew enormous, and virtually unanimous, backing even in deep-red West Virginia and Kentucky, and why 50,000 people marched through the streets of downtown Los Angeles.

“The level of public support was 80 percent for the L.A. teachers,” said Meyerson, an Angeleno himself. “And the biggest strikes of the past year”—all by the teachers—“have been against public authorities and for bargaining for the common good,” with wages and benefits as secondary aims.

That tied into McCartin’s long contention that bargaining for the public good is the way workers can and do win widespread community support and success. Fight for $15, he noted, is a “public good”—a decent living wage. The teachers emphasized crumbling schools and outdated textbooks and, in L.A., an outdated state funding formula which shortchanges public education.

The Chicago teachers wanted to protect their community schools from Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s plans to close dozens of them and run the school district like a business.

Such community-wide organizing is the way to go to succeed in general strikes, the panel said. It’s not enough just to mobilize the labor movement, as corporate chieftains and their political confederates have succeeded in, falsely, painting organized labor into a corner where the rest of the country views unions as “just another special interest.”

The response is to lay the groundwork for general strikes by making sure, in advance, that the public knows they’re in the public interest. That’s what the federal workers did during President Donald Trump’s just-beaten 35-day lockout/shutdown of many agencies. “By the end of 35 days, the public had had it” with Trump, McCartin said.

That emphasis, Meyerson said, can even win for workers in the heavily anti-union South. The area “remains a huge problem” and has been ever since the failed mass 1934 textile strike, which corporate interests and politicians broke, including doing so with race-baiting.

“But West Virginia, Oklahoma, and even Kentucky were rocked by the teachers strikes,” Meyerson added. “Parents want their kids to have a good education.”