Inspired by Germany’s November 1918 Revolution, which was ultimately crushed by the Social Democratic Party leadership and the military, artists and intellectuals, anti-militarists, and pacifists hoped for a new society for the common good. Many, however, had no clear political orientation or a full understanding of the causes of the world war that had just ended. Yet, despite this lack of clarity, socialist visions of the future were formulated, oriented to a more just society.

During its short existence (1919-33), a number of designers and architects emerged from the Bauhaus whose work lastingly influenced 20th-century visual arts. Their philosophy was that everyday objects achieve beauty through simple form, material, and color.

At the initiative of Bruno Taut, Walter Gropius, Adolf Behne, and others, the Workers’ Council for Art—named after the Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils—set itself the goal of bringing current developments in architecture and art closer to the people: “Art and people must form a unity. Art should no longer be the pleasure of a few, but serve the happiness and life of the many.” In Gropius’s words: “the more their class pride grows, the more the people will despise imitating the rich and independently invent their own style of living. This understanding by the people is the fertile ground for the art to come.”

To integrate art and craft

What was new about the school was its attempt to integrate art and craft, to bridge the gap between art and industry. The unity of arts had of course been a central tenet of the late 19th-century Arts and Crafts movement of William Morris and influenced Gropius’s planning for the school. Nevertheless, the Bauhaus was different from the Arts and Crafts movement in fundamental ways. Its emphasis was urban and technological, and it embraced 20th-century machine culture.

The Bauhaus began in Weimar in 1919 as a state school for art and architecture. The guiding principles in the Bauhaus Manifesto were community, unity of art, practical education, cooperation between craft and industry, and a sense of belonging to the people. All artistic disciplines were to be reunited under the leadership of a new architectural art.

The name Bauhaus plays on the German word Bauhütte (construction/building hut)—the workshop where the builders of the great medieval cathedrals worked together: quarrymen, plasterers, mortar-makers, stone-cutters, masons, and others. Here there were no strict dividing lines between artists and craftsmen, and the builders were both in one. This was an important concept for the Bauhaus school. As the word Hütte means hut, the term was modernized to Haus (house). In this way, the term Bauhaus refers to a workshop, the sense of community and the equality of art and craft under the guidance of architecture, as cultivated in medieval cathedral workshops. Painting, sculpture, applied art, music and dance were to combine in the building of the future.

With this commonality of craft and art in medieval cathedral construction in mind, the “Cathedral of Socialism” was understood as a utopian building and embodiment of a future social structure, intended to overcome the consequences of alienation, the causes of which were seen more in the division of labor than in wage labor.

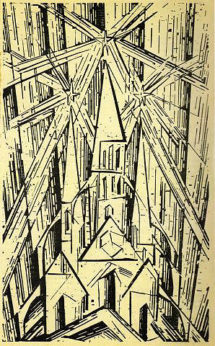

Walter Gropius added this woodcut by Lyonel Feininger to the founding manifesto of the Bauhaus in 1919 as the title page. A triad surrounds the cathedral spire: the three arts of painting, sculpture, and architecture, their rays flowing into each other. The choice of cathedral references the Bauhütte and underlines the centrality of architecture. The old-fashioned woodcutting technique combines with a futuristic cubist design.

At the Bauhaus, painting and sculpture stimulated architecture, applied art, and environmental design. In the visual arts, a certain affinity for the world of technology developed, while industry demanded a species-specific design of its products. The artists broke away from traditional forms; industry presented challenges with a multitude of new materials, products, and devices. Form was to follow function, materials were to reveal the true nature of objects and buildings. Features of an object or building’s construction, such as steel or a beam, were to be highlighted rather than hidden as an integral part of the design, as part of its beauty.

The rectangular shape of the building, glass-curtain walls, and a distinctive vertical logo express the modern vision of the school. Glass walls create a bright interior and facilitate a view into the building’s inner purposes, conveying transparency and openness. These aspects, among others, reflect Gropius’s vision of a more equal society.

At the heart of the Bauhaus philosophy was social living. A house should have a smooth, elementary form, as if it were industrially manufactured. The rectangular system and the Bauhaus signature flat roof were deemed equal surfaces with windows and doors. The aim was to achieve equality between front and rear, top and bottom, right and left. Every element of the building should be both supportive and supported. Architectural ideas reflected social perspectives—a society of equals.

One example of this is the Horseshoe Estate in Berlin. The Horseshoe Estate housed 3,000 members of a trade union building society set up in 1924. Bauhaus architect Bruno Taut, a committed socialist, was asked to plan an affordable estate. The result turned out unpretentious, brick-built modernist flats in dramatic colors. They were then let or sold to trade unionists. The estate’s flat roofs led to a heated debate as the German right considered these un-German, “degenerate.” Indeed, in 1933 when Hitler and the Nazis took power, Taut fled Germany.

The suburban Horseshoe Estate expresses optimism for a new way of life and social equality. As with the school building, each part supports and is supported by the other and all look on to a green communal space around a small pool, fed by ice-age groundwater.

Soviet artists provided inspiration for the Bauhaus: Malevich oriented his suprematist architects toward new architectural ideas of space, Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International illustrated the synthesis between the “technical and the artistic,” and El Lissitzky’s Proun series (pronounced pro-oon), an acronym for “project for the affirmation of the new” in Russian) was conceived as “a transfer from painting to architecture.”

The Thuringian Weimar workers’ government (Social Democrats and Communists) was dissolved in 1923 under pressure from the military. Following a decision by the new government, the Bauhaus in Weimar closed in 1924 with the declaration that Gropius had “designed it one-sidedly communist-expressionist.”

The school moved to Dessau in 1925, against the votes of the right-wing parties there. Following the Nazi Party’s success in Dessau’s local elections of 1931, the German fascists subjected the institution to reprisals, such as raids, and the arrest of students, thus forcing it to dissolve in 1932. Its move to Berlin was short-lived and ended in 1933.

The Bauhaus produced an incredible range of disciplines including theatre design, typography, painting, furniture, architecture, household goods, stained glass, experimental film, photography, music, and dance. Many significant 20th century artists, designers, and architects studied and taught there, including Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Marcel Breuer, and Lyonel Feininger, who designed the cover for Gropius’s Bauhaus manifesto.

Its influence has been enormous: Herbert Bayer’s sans serif typefaces, Gunta Stolzl’s weaving and fabric designs, and Marcel Breuer’s famous tubular steel chair, to name a few iconic designs.

Bauhaus women

Beginning with the Weimar Republic, women in Germany gained the right to vote and the freedom to teach. When Walter Gropius opened the State Bauhaus in Weimar in 1919, he announced in his program: “Every person of good repute is accepted as an apprentice, regardless of age and gender, whose talent and previous training [are] considered sufficient by the Master Council.”

But Gropius soon feared that the large number of women would damage the reputation of the school. He recommended that “no more unnecessary experiments” be undertaken, and demanded, “sharp segregation immediately after admission, especially in the case of the number of women who were too strongly represented.”

The fear was that female students would take valuable workshop places away from male students. Some women nevertheless conquered places in male domains, for example Dörte Helm and Lou Scheper in mural painting, while weaving was declared a “women’s class” from 1920.

The handloom was the only department managed by a woman, Anni Albers. The weaving mill soon became one of the most productive workshops. The ideas and innovations that the women weavers unleashed there were anything but traditional and led to a surge in development in industrial design and an artistic re-evaluation of textile art. In addition, they had such great commercial success that they became representative of the entire Bauhaus.

When Bauhaus architect Meyer asked Albers to produce a wall covering for a new trade union lecture hall he was designing, she created an innovative hanging that joined the new material cellophane with cotton on either side respectively, to produce a surface that absorbed sound and reflected light at the same time.

The second largest area in which women excelled at the Bauhaus was photography. This modern medium offered artistically ambitious women not only opportunities to earn a living but also a field of experimentation for exploring themselves and their time. In their photographic works, these avant-garde photographers dealt with the “New Woman” and the images of women of their time.

In 1933, the Nazis banned many of the Bauhaus students from working. They were persecuted by the fascists because they were political, or they came from political “enemy territory,” or because of their Jewish origin. Their works were classified as “degenerate art.” They left Germany and spread their ideas around the world. When the Nazis built Buchenwald concentration camp, they required the former Bauhaus student and communist inmate Franz Ehrlich to design the notorious camp’s gate, displaying the motto “Jedem das Seine” (To each what he deserves) in Bauhaus typeface, in gruesome irony.

One of the most famous of the women students was Marianne Brandt, née Liebe. László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946) became her mentor and teacher. On his advice, she joined the male-dominated metal workshop. There she gradually gained recognition and designed the first lighting fixtures for the Bauhaus building in Dessau. In 1928, she became head of the metal workshop and made history as a Bauhaus designer. Moholy-Nagy called her his “best and most brilliant student” and said that she was the source of “90 percent of all Bauhaus models.” She became famous for the tiny tea infuser, the “MT 49 tea extract jug” made of silver and ebony, which is still an icon of Bauhaus decoration today, just like her lamp models.

Brandt’s infuser is distinctively Bauhaus. Rather like the infuser used with the samovar, it holds a concentrated extract, which may be combined with hot water to produce tea of any desired strength. Brandt recast the characteristics of a teapot as abstract geometric forms. The body hemisphere rests on crossbars. A tall ebony knob tops its asymmetrical round lid. The D-shaped ebony handle contrasts vertically to the pot’s otherwise principally horizontal lines.

Following their principle “No day without a search,” Brandt also discovered photography. She experimented with perspectives and light and devoted herself to photomontage. She captured themes such as big cities, film. and expressive dance. She critically examined war and militarism and asked how much room for maneuver a “women’s movement” had in her time. Before the Nazis defamed her works as “degenerate,” she was known throughout Europe as a designer, and renowned companies produced her designs in series.

The artistic avant-garde assembled at the Bauhaus hoped to be a force that would change society and shape a modern human environment. It was an important counter-force to conformity, Prussianism, and militarism.

This article originally appeared in Culture Matters.