America finds itself in the thick of a Dickensian narrative, visited by the twin ghosts of racism and sexism past, or, more precisely, of racial and gender violence and injustice past.

The climax of this rocky and treacherous plot is yet uncertain, as we wait to see if the Scrooge that is the American justice system and legislative branch will cease to be blind and mired stubbornly in denial, or if, like Dickens’ Ebenezer Scrooge, they will experience a midnight revelation opening their eyes, hearts, and minds to realize, to see, what is right before their eyes: Black lives and women’s lives do matter, even though historically U.S. society has not treated and valued them as such.

The climax we await is unfolding in two events that, I suggest, we must view as narratives woven together in a singular plot. The climax will be either a dead end or a hopeful hairpin turn.

One of these events is the currently ongoing trial of Chicago Police officer Jason Van Dyke, charged with first-degree murder for shooting Laquan McDonald sixteen times while McDonald walked away from him last October 20, 2014.

The other of these events is certainly more before our eyes these days. Indeed, when one turns on the television, the national news is justifiably dominated by coverage of the drama surrounding Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination process and Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s accusations that Kavanaugh violently sexually assaulted her when they were both in high school.

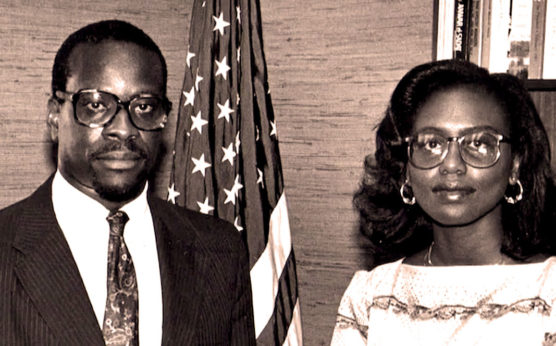

Not surprisingly, this controversy involving a Supreme Court nominee facing accusations of past sexual misconduct has triggered our national historical consciousness to summon the memory of Anita Hill, a figure who has haunted American culture and politics, without us perhaps even knowing it, since her testimony before Congress and the subsequent Congressional confirmation of Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court in 1991.

The climax of those hearings marked a tragically momentous turning point in American history, as the politically conservative sexual predator Clarence Thomas replaced Justice Thurgood Marshall, renowned and vociferous protector and advocate of civil and human rights, on the Supreme Court, endowing him with the power to participate with just eight other justices in making decisions and forging law impacting the lives and rights of hundreds of millions of Americans.

Kavanaugh’s nomination hearing is, indeed, to borrow Yogi Berra’s language, a case of déjà vu all over again. In fact, the same figures and signs abound. Current Senators Orrin Hatch, Mitch McConnell, Richard Shelby, and Charles Grassley played roles in Thomas’ hearings. Hatch infamously accused Hill of manufacturing her account of Thomas’ sexual harassment of her by cribbing it from the novel The Exorcist, as he read passages from the novel and compared them to her account. Now, he accuses Dr. Ford of being “mixed-up.”

The ghost of sexism past is more than present; it is animating the Congressional dynamic. Clarence Thomas referred to his interrogation regarding his treatment of Hill as a “high-tech lynching.” What we have with Dr. Ford and what we had with Hill might fairly be called Congressional legislative rapes. More on this below.

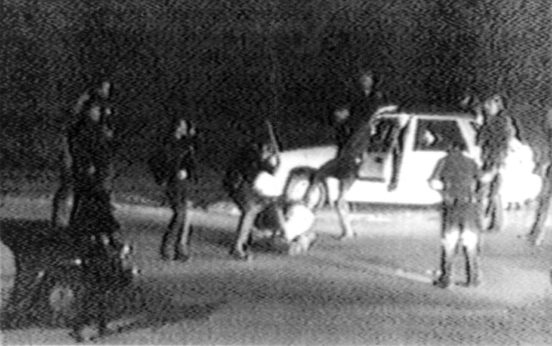

With the fatal shooting of Laquan McDonald and the trial of Van Dyke, we have yet another specter haunting our contemporary moment. The ghost in this case is Rodney King, whose beating in March 1991, combined with the acquittal of the police officers caught on video brutally and repeatedly beating him while he lay helpless and incapacitated, sparked the rebellious uprisings in Los Angeles in 1992.

Obviously, both before King’s beating and between King’s beating and McDonald’s murder, we can identify a string of police violence against, and murders of, African Americans, including Michael Brown, Philando Castile, Alton Sterling, Oscar Grant, Tamir Rice, Freddie Gray, Sandra Bland, and more.

So, indeed, we need to see McDonald’s murder as part of the thread on the long spool rolling back to King and throughout American history, of course.

And this thread and spool needs to be understood as looped in with this violence against and oppression of women in American history and society as well.

Part of what compels me to link McDonald’s murder to the King case is two-fold. One, we have such obvious footage in both cases of wrongdoing and racial violence, that the power of institutionalized racism to distort social vision, to blind, becomes amazingly clear.

And, two, just as King’s 1991 beating and the later trial and subsequent 1992 rebellion in L.A. happened in such proximity to Thomas’ hearing and the persecution of Hill, so is Jason Van Dyke’s trial for the murder of McDonald happening simultaneously with the Kavanaugh hearing and the persecutions of Dr. Ford we are beginning to see in the form of Republican denials.

It is to me more than a little eerie, and far more than an echo, that we see a repetition of the pairing of a Congressional act of violence against a woman speaking out against sexual assault with the trial of police who committed violence against a black man.

That the verdict is yet out, as I write, in the trial of Jason Van Dyke and in the Kavanaugh hearing, but this virtual re-enactment of 1991 will provide us as a society a metric by which to measure our progress, or regression, when it comes to racial and gender equality.

This 2018 re-enactment with Kavanaugh and Jason Van Dyke of the 1991 Thomas hearing and the L.A. police violence invites us, I believe, to study in concert racial and gender inequality, with the violence and oppression that enforce and maintain this inequality, as part of our overall system of structured inequality.

And, as we do that, we need to try to get to the root of the denial of this inequality and the institutionalized practices and moralities that normalize the devaluation of, which realizes itself in violence against, black and female lives. I’m suggesting there is something more fundamental we can analyze in this dynamic by pairing rather than separating racial and gender inequality and violence.

While I’m straining my memory to revisit 1991, I can’t seem to remember the persecution of Anita Hill being viewed together and linked with the beating of Rodney King, but I may be wrong.

In any case, Clarence Thomas did his best to de-link racial and gender oppression. Indeed, Thomas’s defense, I would suggest, rested implicitly on his assertion of his right to enjoy the same rights in patriarchal society as white men do. The “high-tech lynching” he endured was a function of his not being allowed to devalue a woman, especially perhaps a black woman, the same way white men and the dominant culture overall did.

Thomas wanted to argue for his patriarchal rights as a black man, not for equal rights for all.

As we wait anxiously to see what will happen with Dr. Ford’s accusations against Kavanaugh and what will happen in the Van Dyke trial, I’ll suggest we have an opportunity as a culture and society to re-do 1991 and bring renewed focus to our hierarchical structures and penchant for inequality which enable and legitimate violence against women and people of color—and, frankly, many others in our hierarchical class society.

Right now, the assaults taking place don’t bode well for this change. We see the likes of Trump and Lindsey Graham sympathizing with Kavanaugh, making him the victim.

Graham suggests there are special activist interests using Dr. Christine Blasey Ford to derail the conservative agenda.

In some sense, he is right. Her case is about much more than her. It is about all of our rights to enjoy an equal society without sexism and racism, a society in which we recognize that all lives matter by recognizing the ways the lives of women and people of color historically have not in U.S. society.

Call those special interests if you want.

I just hope justice in this country ceases to blind and that we get a little touch of that amazing grace that allows us our justice system and legislators to see. Otherwise, we will not enjoy a Dickensian conclusion to the story—yet.