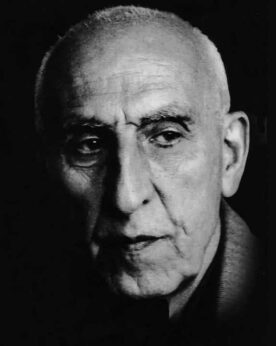

The deposing of Mohammad Mossadegh by a combination of the United States’ CIA and British security forces was not an overnight event. As far back as 1951, there were “concerns,” as British Foreign Secretary at the time, Anthony Eden, late wrote in his memoirs.

“When I assumed the post of the Foreign Ministry on Oct. 27, 1951, the worrying prospect I was thinking about was this: We had left Iran. We had lost Abadan and our power and prestige throughout the Middle East had been severely shaken […] I had to decide how to deal with this situation […] I thought that if Mossadegh fell, it was quite possible that he would be replaced by a wiser government that would make it possible to conclude a satisfactory agreement.”

The “wiser government” which the actions of the U.S. and Britain brought about was that of the shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, heralding in a period of tyranny and oppression which lasted until his overthrow in 1979. That tyranny has since been tragically continued through the theocratic dictatorship of the Islamic Republic.

Mossadegh rose to popularity in 1953 on the back of a wave of disputes with the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), established by the British to exploit Iran’s vast oil reserves and which was increasingly dictatorial with its workforce. In early 1951, in opposition to the decision of the AIOC to drastically reduce the cost of workers’ housing allowance, there were massive strikes in the industry. Mossadegh proposed a plan to the Oil Commission in Parliament for the nationalization of oil.

In March 1951, the Iranian Parliament voted to nationalize oil operations, take control of the AIOC, and expropriate its assets. In May, Mossadegh, the leader of Iran’s social democratic National Front Party, was elected as prime minister and immediately implemented the bill.

Britain responded by withdrawing the AIOC’s technicians and announcing a blockade on Iranian oil exports. Moreover, it also began planning to overthrow Mossadegh. “Our policy”, a British official later recalled, “was to get rid of Mossadegh as soon as possible.”

Mossadegh’s move was a popular one, especially in the context of the revenues from oil being greater than the whole public budget of Iran but not benefitting the people of Iran.

The Mossadegh government had the tacit support of Iran’s Communists in the form of the Tudeh Party of Iran, and the government had cordial ties with the Soviet Union, a significant neighbor and trading partner. The plotting against Mossadegh inevitably used these facts as leverage. The British, in particular, saw that playing up the “communist threat” would be more likely to engage U.S. support than simply wanting to restore British control of the oil industry.

By November 1952, a joint MI6 and CIA team was proposing the overthrow of Mossadegh and initiated actions to arm religious opposition groups to that end. Tribal leaders in the north of Iran were provided with weapons. A combination of activities by British agents provocateurs on the ground and religious forces opposed to Mossadegh resulted in riots in Tehran in February 1953, including attacks upon Mossadegh’s home.

The British utilized the anti-communist card to great effect in attempting to scare Iranians into thinking support for Mossadegh was part of a communist takeover.

CIA officer Richard Cottam later observed that the British “saw the opportunity and sent the people we had under our control into the streets to act as if they were Tudeh. They were more than just provocateurs, they were shock troops, who acted as if they were Tudeh people throwing rocks at mosques and priests.”

A secret U.S. history of the coup plan, drawn up by CIA officer Donald Wilber in 1954, and published by The New York Times in 2000, relates how CIA agents gave serious attention to alarming the religious leaders in Tehran by issuing black propaganda in the name of the Tudeh Party of Iran, threatening these leaders with savage punishment if they opposed Mossadegh.

The final go-ahead for the coup was given by the U.S. in June 1953, with a date set for mid-August. Thousands of dollars were provided to opposition groups to fund mass demonstrations in central Tehran. The military, sympathetic to the shah, took control of the radio station, army headquarters, and Mossadegh’s home.

The shah soon assumed all powers, and the following year a new consortium was established controlling the production and export of Iranian oil, in which the U.S. and Britain each secured a 40% interest—a sign of the new order, the U.S. having muscled in on a formerly British preserve.

The coup and the resultant Shah’s dictatorship not only overthrew the functioning parliamentary democracy in Iran but completely derailed democratic politics. The shah established a reactionary political system where his own devotees, along with a pliant Islamic clerical hierarchy, determined the composition of the parliament. All progressive political parties, including the communist Tudeh Party of Iran, were banned and forced to undertake clandestine activities.

By 1979, the Islamic institutions were in effect the only players freely operating on the political scene in Iran. The Islamists exploited the monopoly of their legally operating mosques in all towns and cities to move against the shah with their own “Islamic Revolution.” Their power ensured that they had absolute control over shaping the new regime. The left and progressive forces were violently suppressed and their impact marginalized. A new dictatorship was in total control by 1983.

The U.S. formally admitted its role in the 1953 coup 10 years ago with the declassification of a large volume of intelligence documents, which made clear that the ousting of the elected prime minister, Mohammad Mossadegh, 70 years ago this week, was a joint CIA-MI6 endeavor. The formal U.K. government position is to refuse to comment on an intelligence matter.

Via Liberation