At a time when superhero and other action flicks explode and careen across our screens, with its decidedly indie sensibility, Max Walker-Silverman’s little gem A Love Song goes against the blockbuster grain. It is as gentle as Marvel Universe flicks are violent. With its simple, naturalistic style tinged by sly humor, A Love Song is a motion picture paean to the human condition, filled with yearning, grief, loss and the quest for meaningful (if not necessarily long-lasting) connection and love.

Except for the fact that she’s blonde, Faye (Dale Dickey) is not your conventional looking movie star and love interest. She is 60-ish and looks it, with a lined face, that’s recurringly shot in long, lingering closeups. Faye is living out of a trailer at a campground in Colorado (the license plate of a vehicle is the only specific clue that this story is set and shot in the Centennial State). Living close to nature, Faye catches lobsters or crawdaddies out of the lake that is her rustic front yard, identifies the calls of various birds and the species of different flowers, as she awaits the arrival of a male friend from her childhood and teenage years (or was their relationship more intimate?) on a yet-to-be-determined date.

While she waits, Faye lives a mostly solitary existence with the silence occasionally broken by the arrival of Postman Sam (John Way), who delivers mail on foot to campgrounds residents. In a couple of comic scenes shot with a sort of silent screen slapstick panache, four grownup cowhands appear out of thin air, led by Dice, a little girl crowned by a 10-gallon hat (the exceedingly charming, droll, scene-stealing Marty Grace Dennis), who does the apparently Caucasian quartet’s talking for them in a quirky if not grandiloquent manner.

At one point a pair of African-American lesbians who are Faye’s campground neighbors invite her to supper. Their breaking of bread allows for some of A Love Song’s sparse dialogue, which centers on ruminations about the film’s eponymous eternal theme, love. Now that it’s legal for them to do so, the same-gender couple is pondering whether or not to make it official and get hitched. But Marie (Benja K. Thomas) reveals that her nervous partner Jan (Michelle Wilson) is hesitant or scared about popping the question.

After days pass with no sign of her long-lost friend’s arrival, Faye, who has the habitude of individuals living in solitude—ever notice how people who complain about loneliness often push people away?—decides to leave the campgrounds. But fate has other plans for her. In the tradition of Homer’s Penelope, Faye stays put until 27 minutes into this odd odyssey, when Lito (Wes Studi) finally makes his not-so-grand entrance at campground site #7 (which Faye had chosen because seven is supposedly a lucky number).

A Love Song focuses on the reunion of these two aging adults who were close 40 years ago. Whether or not they had a romance back in the day, they each went on to marry different spouses who were part of their youthful circle but are now dead. Throughout the day the now once again single Faye and Lito strive to reconnect, asking at first, “Do you know me?” That, of course, is one of the great metaphysical questions of all time: Can one ever truly know another, let alone one’s own self?

Meanwhile, back at the movie, the reunited old friends reminisce, play music together, enjoy the lake in a kayak quirkily bequeathed to Faye by the talkative Dice, fish, eat and drink. When nighttime arrives the great unanswered question is: Where will Lito sleep? This plot spoiler averse critic won’t ruin your delight in discovery.

A Love Song poses many other questions. Once one has reached the point where most of one’s life is in the rearview window, can one find something or someone new looking through the windshield that makes it worthwhile and interesting to keep on keeping on, as one pushes down the long and winding road of existence? Can senior citizens still find and enjoy romance, sexual intimacy and pleasure? Or as the Clash’s popular punk rock anthem puts it: “Should I stay or should I go?”

The movie that A Love Song most reminds me of is that other indie about an older woman who’s largely alone, pursuing a nontraditional lifestyle in the West, 2020’s Nomadland, which lest we forget won three Academy Awards for: Best Picture; Frances McDormand for Best Actress; and Chloe Zhao for Best Director, and was also Oscar nominated in three other categories. A Love Song has a very similar vibe to Nomadland, and I wouldn’t be surprised if Tennessee-born Dale Dickey was likewise nommed for one of those coveted golden statuettes, even if this independent film is not your typical Hollywood fare. (Don’t expect a Love Song franchise.)

Dickey is one of those actors whom many casual moviegoers and TV couch potatoes are likely to immediately recognize, although few will remember the veteran’s name. Her long list of credits includes 2010’s Winter’s Bone (which memorably unleashed Jennifer Lawrence upon the world) and the HBO modern-day vampire series True Blood.

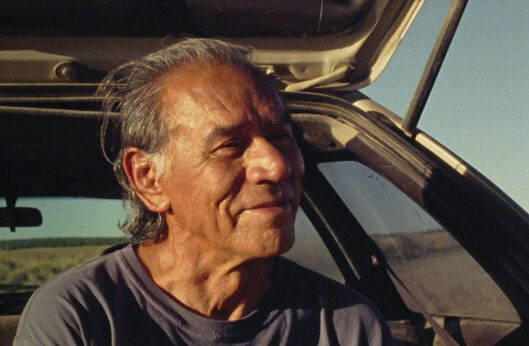

Given this film historian/author’s interest in the Indigenous screen image, I’ve followed the career of Oklahoma-born Wes Studi at least since 1993, when he played the title role in Geronimo: An American Legend. The craggy-faced Cherokee actor is almost 75, but the still handsome Studi wears his years well. In 1992 Studi played Magua, the savage antagonist of the screen adaptation of James Fenimore Cooper’s frontier classic set during the French and Indian War, The Last of the Mohicans, opposite Daniel Day-Lewis. The quintessential Indigenous actor, Studi also depicted the tribal police officer Joe Leaphorn in the Skinwalkers television series and TV movie adaptations of Tony Hillerman’s novels set in the contemporary West. He also acted in the great 1988 “Red Power” movie Powwow Highway, 1996’s Crazy Horse and 2007’s Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee.

I had the good fortune of meeting the gentlemanly Studi once and have seen his likewise gifted niece DeLanna Studi perform at the Autry Museum’s Native Voices, where she became co-artistic director of the only Equity theatre company dedicated exclusively to developing and producing new work by Native American artists. In A Love Song Studi plays against type—no war bonnets or warpaint here. I’m not even sure that it’s made clear in the dialogue that Lito is indeed of Indigenous ancestry (as opposed to, say, being primarily Latino-identified), even though he’s portrayed by a Cherokee actor.

Nothing is made of the fact that the blonde Faye and darker skinned Lito have an interracial relationship. Screen romance between Indians and “palefaces” has long been a taboo topic since Cecil B. DeMille’s 1914 The Squaw Man, and is the impetus for 1956’s John Ford classic The Searchers, with morbid loathing of miscegenation motivating John Wayne’s odyssey to “rescue” the absconded Natalie Wood. But here, in the 21st century’s A Love Song, nothing is made of the different ethnic backgrounds of Faye and Lito, who have much more in common as humans looking for love than they do differences.

Interracial mating and dating, which literally inspired the Ku Klux Klan to ride to the rescue of the blonde Lillian Gish’s hymen in D.W. Griffith’s 1915 racist epic The Birth of a Nation, is today far more widely practiced and accepted in reality and onscreen, from endless TV commercials with multi-culti characters to movies such as A Love Song and the upcoming Three Thousand Years of Longing pairing Idris Elba and Tilda Swinton. Thankfully, this once forbidden love is no longer one of those loves that dare not say its name (that is, not unless the Supreme Court’s witch-hunters overturn the settled law of 1967’s Loving v. Virginia case).

In A Love Song Studi sets a new template for tribal actors in that his Lito is a completely current contemporary character, not an exotic “other” from long ago and far away or living on a remote reservation. In fact, the quintessence of A Love Song is its deep humanity. Be they Caucasian, African-American, Indigenous or any person of color, straight, gay, male, female, the dramatis personae have a common humanity. They all share a need and desire to feel connected, to love and be loved—and if they’re lucky enough, to sing about it.

A Love Song is 81 minutes and being theatrically released July 29.

Comments