LOS ANGELES—“War, what is it good for? Absolutely nothing!”

That was the battle cry of Rosalio Urias Muñoz on September 16, 1969. On that day he refused induction into the armed services by burning his draft card in front of the recruitment office. This singular moment in Rosalio’s life is depicted in the sidewalk mosaic located in front of Los Angeles Councilman’s Gil Cedillo’s field office, located on N. Figueroa St. at N. Ave. 56. It is one of the several sidewalk mosaics installed on Figueroa St. as part of the Angels Walk of Highland Park.

The unveiling of these mosaics occurred on April 24th of this year during a ribbon-cutting ceremony led by 1st District Councilman Cedillo, mosaic artist Raul Alexander, and Rosalio Urias Muñoz, historian and social justice activist. Prior to the ceremony, Councilman Cedillo delivered a brief explanation on the history of Highland Park and the creation of the mosaics. He also expanded on how Rosalio influenced his life as a union labor leader.

The Angels Walk of Highland Park is only one of a series of eight walks located within the City of Los Angeles. Each of them is highlighted by a guidebook map and street stanchions describing the historical sites and sights of the neighborhood. These walks provide information on the diverse culture and history of the various ethnic groups that reside or have resided in these areas.

Rosalio was selected for one of the mosaics because he lived and grew up in the Highland Park area. His mother, Maria Muñoz, was a 6th-generation Mexican-American and member of a founding family in Tucson, Arizona. His father, Dr. Rosalio F. Muñoz, was one of the first Mexican Americans to obtain a doctoral degree in the fields of social work and education.

Rosalio attended local Highland Park area schools, graduated from Franklin High School and attended the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA). While attending Franklin High School, he was involved in student affairs and was a student body officer. He carried over this experience to UCLA, where he was elected the first Mexican-American student body president.

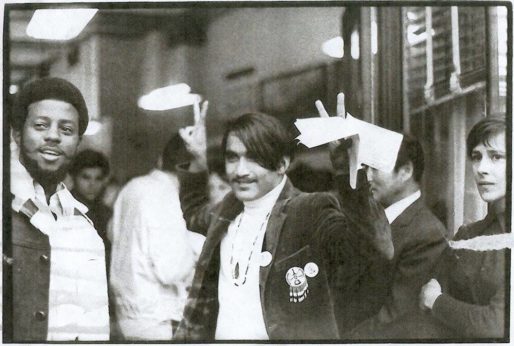

During this time, he met and became involved with Father John Luce of the Church of the Epiphany in Lincoln Heights. This is where he became interested in social justice movements that involved the immediate community. He focused on raising awareness of the mortality rate in Vietnam and Southeast Asia and on promoting peace, which led to organizing the Chicano Moratorium Committee and planning demonstrations against the atrocities of waging war.

The Committee decided to organize a protest march and rally to bring awareness of the high mortality rate of Mexican-American male youth. The march was planned to start at Belvedere Park and end with a rally at Laguna Park.

On August 29, 1969, a sweltering summer day, 50,000 students, community members and families from Los Angeles and the Southwest United States converged on the streets of East Los Angeles to voice their outrage against U.S. policy in Vietnam. Shortly after the crowd assembled, to watch entertainment and hear speeches at Laguna Park, L.A. county sheriffs began to move into the crowd at the northwest corner of the park. People and families were dragged, beaten, arrested and killed, including the Los Angeles Times reporter Ruben Salazar, who was covering the event for the newspaper.

This momentous event led Rosalio to continue in the struggle for social justice. He was involved in La Marcha de la Reconquista (the March of the Reconquest), on May 5, 1971, which was a 1000-mile march from Calexico, Calif., to the state capitol at Sacramento. The goals of this march included: Farmworkers’ rights, improve public education, overreaction of police, welfare rights, and prison reform.

Throughout his lifetime, Rosalio has recorded and collected a mass of photos and information on social struggles of Mexican Americans in Southern California. Currently he is curating and archiving his collection and writing his memoirs. Among the topics he has curated are the history of the Church of the Epiphany, including its role as a social justice center; pre-1969 school walkouts, the Chicano Moratorium, and the life of labor leader Bert Corona. He continues to be active in contemporary social justice struggles. He recently exhibited some of his photos and writings as part of the Epiphany Art of Protest, which also included work by various other artists influenced by past and current social justice movements.

Public art exists to commemorate those aspects of history we choose to remember and honor. A mosaic such as this one of Rosalio burning his draft card is out there for all to see and ponder. As people stand there and absorb the meaning of this monument they may ask, What is the role of social justice in the present worldwide political climate? How do people become motivated and organized to become involved in social justice issues? How do students stay guided to continue their struggle against gun violence and for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA)—the Dreamers?

May the spirit and the energy of the movements to which Rosalio supplied real leadership, and may his historical research and writing contribute to inspire all who encounter his work toward a true social justice society.