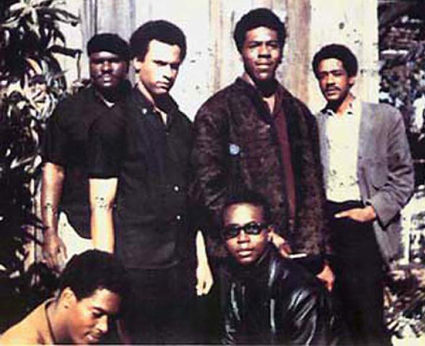

One of the original founding members of the Black Panther Party, Elbert ‘Big Man’ Howard, has passed away at the age of 80. He, along with Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton, was one of six people who founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Oakland in October 1966. Howard was an active member of the party from its founding until 1974. He served as the first editor-in-chief of the party’s newspaper, along with being the party’s Deputy Minister of Information, a member of the Central Committee, and a member of the International Solidarity Committee.

The Black Panther Party came out of the growing Black Power movement to empower African Americans in the U.S. against oppression and poverty under a system embedded with racism and white supremacy. The inception of the party came on the heels of turmoil in the late 1960s. The Civil Rights Movement had done much in the fight for equality, but high unemployment, decrepit housing, lack of political representation, and police brutality in predominantly Black neighborhoods had many members of the younger Black generation at the time seeking more thoroughgoing change. One of the BPP’s first acts was organizing members to undertake armed patrol of police officers to prevent continued brutality against Black residents.

Howard at one time recalled the tension in the neighborhoods of Oakland, California, where he settled down in 1960 after serving in the Air Force from 1956. “Oakland seemed to have a thriving Black community with friendly people. However, the lines of segregation were clearly drawn with the city’s storm troopers there, to keep Black people in line and not crossing it without deadly consequences. These deadly consequences were carried out almost weekly with White cops killing Black citizens. Without exception it was officially termed ‘justifiable homicide’ by the police and city officials,” he explained.

The BPP ran a number of what it called Community Survival Programs. One of the most popular, the Free Breakfast for Children Program, saw the party set up kitchens providing meals to 20,000 school-aged children in 19 cities around the nation. The party also adhered to a Ten-Point Program that included ideals such as wanting full employment for African Americans, an immediate end to police brutality and murder, and “land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice, and peace,” for Black people. Howard’s ex-military background made him invaluable to party security and safety protocol. In a 2012 interview with the North Bay Bohemian, former BPP chairman Bobby Seale said of Howard, “We were ex-military…. We were able to show other party members the use of guns and weapons, and the safety of weapons…. Elbert Howard’s experience was invaluable.”

In his years after leaving the BPP, Howard continued his activism with various projects. He was a coordinator for the All of Us or None Ex-Offender Program, a member of the Millions for Reparations committee, a founder of the Police Accountability Clinic & Helpline of Sonoma County, and a board member of KWTF, a community radio station. Howard would continue his political writing through various essays, along with a memoir entitled Panther on the Prowl, covering his time in the party and what he considered the reasons for the rise and fall of the organization.

Howard wrote on various topics, including the importance of solidarity, the role of rank and file members in an organization, and the corruption of the government and political and economic systems. On solidarity, Howard recalled how the BPP employed the strategy in order to make major campaigns successful. “Because of strong solidarity with these many different groups, the Black Panther Party was able to amass great numbers of people to participate in demonstrations such as Free Huey, Stop the Draft, and End the Vietnam War rallies, which occurred all over the country,” he wrote in an essay entitled Solidarity.

Howard is survived not only by his wife, children, and grandchildren, but by a legacy steeped in struggle, resilience, and Black power. Even in his years after leaving the BPP, he continued to push the oppressed to rise up against oppression. In a 2005 essay entitled How I See It, Howard wrote, “As I see it, people would be well-advised to study history and learn from it. Look at how programs such as the Free Breakfast Programs, Community Control of Police Programs, and Medical Clinics were developed and instituted by the Black Panther Party within so many communities. People must pay attention and come together if we are to save ourselves.” Howard’s deeds and words leave inspiration to continue on with the fight for true democracy and equality.

Compiled and written by Chauncey K. Robinson.

Like free stuff? So do we. Here at People’s World, we believe strongly in the mission of keeping the labor and democratic movements informed so they are prepared for the struggle. But we need your help. While our content is free for readers (something we are proud of) it takes money — a lot of it — to produce and cover the stories you see in our pages. Only you, our readers and supporters, can keep us going. Only you can make sure we keep the news that matters free of paywalls and advertisements. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, support our work by becoming a $5 monthly sustainer today.