DETROIT—Thirteen years after General Motors fired injured auto workers at its Bogotá, Colombia, Colmotores plant, workers continue their tent encampment protest outside of the U.S. Embassy there.

The workers that formed the Association of Injured Workers and Ex-Workers of GM Colmotores, or ASOTRECOL, are demanding that GM return to a mediation process originally initiated in 2012. The company walked away from the table and has refused to honor its agreement to settle the labor dispute ever since.

Countless auto workers at Colmotores faced injuries, including herniated discs, back problems, carpal tunnel syndrome, and others. Many workers have been left unable to work again due to debilitating conditions.

The workers who formed ASOTRECOL were among hundreds suffering work-related injuries and discharged at GM Colmotores. In many cases, their medical records were tampered with, rendering them ineligible for disability pensions. Workers who took their cases to court found the system was rigged against them.

Workers at the 1970s-era plant were routinely being fired after suffering disabling injuries assembling Chevrolet subcompact vehicles and light trucks for the local market. The Fábrica Colombiana de Automotores (Colmotores), incorporated in 1956, was purchased by General Motors in 1979 when the auto giant acquired nearly four-fifths of the Colombian firm’s shares, thus gaining total control. Since then, the Colombian subsidiary of General Motors was renamed General Motors Colmotores.

The company’s domination of its workforce initially proved effective at isolating ASOTRECOL. There was GM’s company “union”—the Collective Pact—which workers were required to join upon being hired under one-year contracts. The workers were forbidden from joining the National Union of the Metallurgy Industry (SINTRAIME), but even the latter’s support for ASOTRECOL was limited to an endorsement of the Association’s claims.

After taking the issue to Colombian government regulators, who had no interest in holding GM to account, on Aug. 2, 2011, they set up tents in front of the U.S. Embassy. They hoped that the Obama administration would compel the company to uphold workers’ rights. At the time, the U.S. government was a major GM shareholder due to the terms of the taxpayer-funded bailout given to the company after the financier-caused Great Recession of 2007-08.

The workers were met with disappointment; neither GM nor its U.S. government owners paid any mind to their grievances.

GM refused to negotiate with ASOTRECOL members throughout the first year of their encampment in front of the embassy. It was only when the workers staged a hunger strike, with their lips sewn shut, that GM took notice.

At the time, then-AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka issued a “Call for Immediate Action.” In it, he stated that the “U.S. and Colombian governments must bring GM Colmotores into dialogue with ASOTRECOL to help facilitate a swift and fair response to the workers’ grievances.” Furthermore, he called on the Colombian Ministry of Labor to “thoroughly examine General Motors’ occupational health and safety practices and the use of a ‘collective pact’ in Colombia for compliance with national law and the labor provisions of the Colombia Free Trade Agreement.”

Twenty-two days into the hunger strike, GM agreed to a mediation under the auspices of the U.S. Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service. It was only then that Joe Ashton, then-Vice President of the UAW GM Department, flew to Bogotá to accompany the GM executives for talks. Three days into the mediation, GM abruptly made its “final offer,” which was deemed wholly inadequate by the workers, prompting them to decline it. The proposed cash settlement wouldn’t have even covered their needed surgeries. GM simply walked away.

In the ensuing years, ASOTRECOL members say they couldn’t get much support from the UAW International Union. But that’s changing with the new leadership elected last year by the UAW rank-and-file after the latter endorsed a historic “one member, one vote” referendum.

One of the union’s newly elected leaders is Vice President Mike Booth, who is also the director of the UAW’s GM Department. He and President Shawn Fain, along with five other reform candidates, were elected with the support of the reform caucus, Unite All Workers for Democracy (UAWD). At the UAWD’s first convention last September, Booth spoke on behalf of the International Union in support of a “favorable and just settlement” for ASOTRECOL.

Frank Hammer, former president of UAW Local 909, has been intimately involved in the solidarity efforts since 2012. He has been leading protests outside of the GM Renaissance Center, the headquarters of the auto giant in Detroit, with the Autoworkers Caravan group and has been in constant contact with auto workers and union leaders in Bogotá. He’s been raising the issue of working-class internationalism and solidarity with the Colombian auto workers ever since, in union and human rights gatherings in the Midwest, Canada, Germany, and South Africa.

In 2013 and again in 2018, Hammer and his fellow workers traveled to visit the tent encampment in Colombia and met with the U.S. Embassy, the City of Bogotá, Colombian Ministry of Labor officials, leaders of the Central Unitaria de Trabajadores de Colombia (Colombia’s main labor federation), AFL-CIO Solidarity Center representatives, renowned Colombian Jesuit priest Francisco de Roux, and others.

But trying to get the UAW International Union to do more for the workers during that time wasn’t easy. “That is, until the election of Shawn Fain as president of the union,” Hammer told People’s World.

“Back then, when I presented the Colombian auto workers story to the annual conference of the Latino Workers Leadership Institute in Dearborn, it was all new to them,” he said. “UAW members in attendance were surprised that they hadn’t learned about it from their union.

“The fact that the UAW discontinued its support of ASOTRECOL and kept mention of their struggle out of UAW publications or the website was difficult to comprehend. The same goes for why other unions were tacitly or actively discouraged from assisting the Colombians, like the Canadian UNIFOR, the Steelworkers, or UNITE in Britain.”

Despite the lack of support by the UAW International at the time, rank-and-file autoworkers and local unions were extremely supportive. In 2013 alone, the solidarity network built inside the union raised more than $10,000 from Toledo Locals 12 and 14, Detroit-area Locals 22, 140, 412, and 869, and Retiree Chapters from Locals 235, 262, and 909 at their meetings or at the plants, Hammer said.

In a huge act of solidarity, alongside the Auto Workers Caravan, the locked-out UAW Local 9 Honeywell workers in South Bend, Ind., shared with ASOTRECOL a third of the donations they received from local churches, union locals, and others ten months into their battle against the company there in 2017.

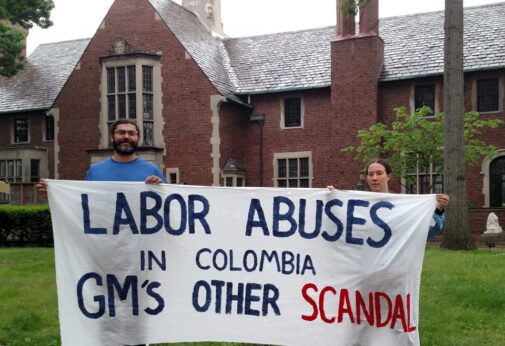

“We rallied and picketed at GM headquarters, auto dealerships, GM Board of Directors’ and executives’ mansions, auto shows, auto industry conferences, and more,” Hammer said. “We brought banners saying, ‘GM–Workers are not Disposable’ and ‘Justice for GM Hunger Strikers.’ One of our union brothers, Melvin Thompson, a former Local 140 president, initiated his own 22-day liquids-only fast in 2013 in solidarity with ASOTRECOL members who were on hunger strike.”

Even though they were fighting a goliath, ASOTRECOL was still able to make gains thanks to their own heroic efforts against GM and the solidarity shown by auto workers in the U.S. and human rights groups like the Portland Central America Solidarity Committee in Oregon and the Michigan Coalition for Human Rights.

Their exposure of GM’s illegal practices, for example, slowed down the rate of firings of injured workers and improved conditions in the factory, including garnering a $3 million investment in ergonomics improvements. The fact that dozens of fired injured workers fought back by organizing themselves inspired other injured workers—not only in the plant but throughout Colombia.

“Injured workers who were still on the job formed their own in-plant defense organizations—the association UNECOL, and a first-of-its-kind, injured workers’ union—UTEGM—the latter with direct assistance from ASOTRECOL,” Hammer told People’s World.

In 2014, after pressure from rank-and-file workers, the President and Secretary General of the largest labor federation in Colombia, the CUT (Central Unitaria de Trabajadores de Colombia), publicly denounced GM in support of ASOTRECOL and urged the company to reach a settlement.

GM continued its unlawful abusive behavior in 2016, however, by firing another 40 injured workers—24 of whom filed claims in court. ASOTRECOL’s ability to shine a light on GM’s malfeasance helped them win their cases. The judge cited the international support shown for ASOTRECOL as part of his written decision. GM reinstated all 24 workers but later re-discharged half of them. GM was content with defying judges’ orders and even fines levied by the Colombian Labor Ministry.

At a 2018 GM shareholders’ meeting, CEO Mary Barra insisted that there are “no issues” at the Colombia plant, yet the company claimed it made “very generous offers” in 2012 to ASOTRECOL to arrive at a “win-win” solution.

“As a UAW Shop Chairman at GM Powertrain Local 909 and as an International Representative in the UAW-GM Dept. Umpire Staff, I’ve never witnessed GM make an offer, much less a generous one if there wasn’t an issue,” Hammer said.

In a serious blow to the Colombian working class, GM announced in April of this year that it was shuttering the Colmotores plant completely and eliminating nearly 850 jobs. Over the past 15 years, the plant had already decreased its workforce by more than half and was still reducing it, even with the addition of a heavily automated stamping area.

While the struggle of the Colombian auto workers against corporate giant GM for justice and reparations is not over, this year’s move by the UAW leadership to support the injured workers there is encouraging. Under Fain’s leadership, the UAW has been stepping up its support of ASOTRECOL.

As of now, it’s still unclear what resolution the injured workers in Bogotá can hope for given the shuttering of Colmotores. They wonder whether GM will settle through mediation.

For over a decade, the company has relentlessly fought, denied, and stalled on the demands made by ASOTRECOL, but with the renewed efforts by the UAW International Union, trade union, and solidarity activists are hopeful that the workers may finally get the relief they deserve.

Frank Hammer contributed material for this story.

Solidarity activists continue to materially sustain the Colombian workers’ struggle. If you wish to contribute, please click on a GoFundMe page, here.